Chairman Reaches for the Stars on Patients’ Behalf

In the Hobbs household, Popular Science was the favorite magazine.

It was the mid-1900s when Helen and Ernest Hobbs were bringing up their four children in Augusta. Bugs Bunny and the ball point pen had made their debut. Test pilot Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier, and the first organ was transplanted. The news was rife with the Cold War and the country’s space race with the Soviet Union. DNA was discovered, cigarettes were linked to cancer, and the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregation was “inherently unequal.” The Soviets launched Sputnik I in October 1957, and nearly a year to the day later, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration was born.

Blazing Trails

Even though he could not vote or finish high school in his native Jefferson County, Georgia, the man who would become patriarch of the Hobbs household served in the U.S. Navy in World War II. As is common in tiny communities, Ernest already knew of Helen, and when he came back from service, he officially met and married her. They were an interesting match. He was a natural diplomat and self-made educator who worked two jobs to support his family. She was more of a radical, keenly aware of how smart she was and often vocal with her frustration working as a domestic when skin color was the only difference between her and her employers. Their first child, Joseph, hoped to grow into an amalgam of the two.

His childhood was idyllic by many measures. Ernest helped Joseph with his science homework, and his mother helped with the rest; they would talk about the science of the day and the flying cars of the future.

Ernest would bring home Popular Science. “That was all a part of the stuff that was at the kitchen table in our house because of my father,” Joseph Hobbs says, reminiscing about evenings at the kitchen table, Saturday afternoons watching his father bring televisions back to life, and Sundays listening to Ernest teach, not preach, at their small country church. Helen taught catechism on Sundays, but instead of captivating a room, she would cast her spell one soul at a time.

Joseph Hobbs also found himself wanting to blaze some trails.

Practice , Practice , Practice

He was a fourth-grader at the new all-black Levi White Elementary School in Augusta. While science fairs weren’t included in the curriculum, his class built a six-foot aluminum foil-covered rocket with fins; he and his classmates played the planets. Hobbs was Mars. “I really wanted to be Jupiter, because that was the big one,” he says. Plus, despite being named after the Roman God of War, Mars didn’t have much of a speaking part, no doubt poor casting for the typically enthusiastic Hobbs.

Teachers at nearby Lucy Laney High School got wind of their efforts and invited the children to their fair. In between circling the sun, Hobbs got to share what Mars did, and it felt good to be able to answer older kids’ questions. “It was at that moment when I said to myself: ‘I know this stuff,’” a sense of satisfaction that fueled his desire to nail other things as well as he had nailed Mars. Music lessons taught him that his future likely did not include being in a band, but the trumpet reinforced parental lessons about discipline and focus. If you waited for the next band practice to play, “you lose your lip,” says Hobbs. So he practiced, practiced, practiced and still does.

When Alan B. Shepard Jr. made the nation’s first suborbital flight and John Glenn its first orbital flight, Hobbs thought maybe he’d find his magic in designing rockets. “We were fascinated with these heroes who were willing to sit themselves on top of a candle and go into space.” The space shuttle Challenger team is his screen saver to this day, and at least part of Hobbs wanted to be in space.

But the math rang in his ears. There were lots of NASA engineers and a comparative handful of astronauts. Besides, although he continues to count them among the nation’s true heroes, Hobbs saw astronauts as a sort of guinea pig while engineers helped ensure they survived the high-stakes experiment. So in the ninth grade, he helped birth the Augusta Rocket Club. Although the first members would certainly have liked to build and launch their own, they took the safer approach, putting prefab engines inside a vehicle they designed that would barrel up maybe 700 feet, then quietly return with a parachute.

No doubt, they were the school nerds, but every once in a while, Augustus R. Johnson Junior High would empty and the students would form a large circle around the nerds and watch the rockets soar. There was that one incident where they accidentally launched a rocket inside, but all appendages as well as the Rocket Club survived.

Biology entered the scene about then, as the nerds started wondering about the impact of such powerful acceleration on people, but they started with mice. This is also where Hobbs offically met the Medical College of Georgia.

Dr. William S. Harms was an MCG biochemist who spent occasional Saturdays with the students, analyzing the impact of mice spinning in centrifuges to mimic what happens to astronauts. Rosa T. Beard, a longtime science teacher and adviser to the now-famous rocket club, knew Harms. With just a 10-minute walk between them, he would often help her school out when they ran low on science supplies. Hobbs isn’t certain but reasons that the relationship also earned them the Saturday mornings at the state’s public medical school. Harms seemed to take a particular interest in Hobbs, giving him additional insight into how the body works. Some of it was lost on Hobbs, but what stuck was a love of biochemistry. And talk about a twofer.

A Circuitous Route

Harms worked with Dr. Claude-Starr Wright, who’d been recruited as the first Chief of Hematology when MCG opened its first teaching hospital in 1956. Wright would show up to talk with Harms, and Hobbs was often there. That connection led to a summer research job during college with Wright, who was studying erythropoietin, a protein critical to making red blood cells. Some Saturdays, Hobbs also got to go on patient rounds and began to see great medicine practiced. That included faculty, including Wright, always showing great respect for patients, including small things such as washing his hands before he touched them. The “little black kid in a white environment” even met famed Dr. Titus H.J. Huisman, a giant in blood diseases. Hobbs remembers much later, as a first-year medical student, arriving late to one of Huisman’s lectures. Huisman waited for Hobbs, then asked his permisson to proceed. His entire class of 136 laughed with him.

Medical school was a bit of a circuitous route for Hobbs, but life was like that then. The difficult first chips at segregation were being made, and colleges and universities, including Hobbs’ undergraduate alma mater, Mercer University in Macon, Georgia, were working hard to integrate by scouring the honor roles of black high schools such as T.W. Josey High School in Augusta. The smart but poor Hobbs took a chance on the full scholarship at the private school, acutely aware of why and how he arrived. Four black students had previously attended Mercer; Hobbs was one of 16 in 1966. “We were the second big wave.” With the Hobbs family mantra that education was something no one could take away, he focused on learning but acknowledged the social isolation. One Sunday, the wave of 16 dispersed throughout the campus lunchroom, rather than sitting together per usual.

“It was hard. It kinda let you know that the process of integration was not as simple as just taking two different kinds of people and putting them on the same campus,” Hobbs says. “Some of the separation was based on racism; some of the separation was based upon doing what you were familiar with.” There was clear hesitation that Sunday, but the white students eventually joined them. Hobbs comfortably kept his seat. “I was doing my Stokely Carmichael thing,” he says with a laugh. Something about the give and take worked. By the time he graduated, Mercer’s freshman class had 40 black students, and they didn’t have to be recruited. In fact, two of Hobbs’ three children are Mercer graduates.

Next Stop : Harvard

Mercer didn’t offer a biochemistry major, so Hobbs majored in biology, hoping to teach biochemistry at a university. When he was a rising senior, Harvard University came looking for him for a summer program. Hobbs was in Harvard’s Matthews Hall when Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon. “That was the nature of that summer,” he said, reminiscing about working in the lab of a scientist collaborating with Drs. James Watson and Francis Crick of DNA double-helix fame. “I stole a couple of pencils for keepsakes,” Hobbs confesses. He was accepted into Harvard’s PhD program, as well as the University of Chicago’s and several others. His early mentor, Wright, had convinced him to also apply to medical school, and he was also accepted at that now-familiar setting of MCG.

The Vietnam War was accelerating, and Hobbs drew a low lottery number in the draft. There was no deferment for graduate school, and while he had not formed strong political views about the controversial war, he knew people who had died in it.

That was scary, as was the thought of interrupting the educational cycle that brought him to this day. He thought of Wright, his only real role model in medicine, because his family could not afford the regular medical care he now advocates. As he was struggling with his choices, Dr. James B. Puryear from MCG Student Services showed up at Mercer to talk with some premed students. Hobbs came along to hear what he had to say and was surprised when Puryear singled him out as one of the first Mercer students accepted to MCG, a powerful message particularly to the only black man in the room.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]“I was not there because of my race or because I was poor. Those were things that motivated my recruitment, but I deserved to be there. That evidence was provided by MCG.” –Dr. Joseph Hobbs[/su_pullquote]“I just saw the world becoming equalized at least from an academic standpoint – that whether they liked it or not, they had to accept that I was a competitive peer and I deserved to be there. I was not there because of my race or because I was poor. Those were things that motivated my recruitment, but I deserved to be there. That evidence was provided by MCG,” he says. Harvard would counter-offer with a then-innovative MD/PhD program, but Hobbs was still not interested in being a guinea pig.

Fire in the Belly

At MCG, he was among a second wave of black students. Among his seven black classmates in the class of 1974 were future doctors such as Ron Spearman, who helped light a physician fire in his belly and inspire him even on the longest days. He began to view physicians as servants and thinking maybe he could be one. The world and Hobbs had continued to change. But his parents’ inspiration as great teachers on those Sunday mornings and at the kitchen table was ever-present.

Time would fly by, and he and Spearman would become MCG’s first black chief residents. His chosen specialty, family medicine, which has been around essentially forever as family or general practice, became a board-certified specialty in 1969. Departments of Family Medicine were forming in medical schools, and Hobbs had the opportunity to get in on the ground floor of MCG’s.

The primary care specialty was not always a welcome addition in the subspecialist sea that comprises the

majority of medical school faculties. External pressure from the state’s family physicians added credibility to the need for a Department of Family Medicine at MCG, as the state was struggling – and continues to struggle – to provide enough primary care physicians. The department was five years old when Hobbs joined the faculty in 1977. This time, he made the first wave: the new department’s first black faculty member.

Scouring the State

Like the Rocket Club he started, Hobbs had plenty of ideas about what needed doing now that there was a different fire in his belly. While fellow faculty member Dr. Ohlen Wilson seemed an unlikely partner when Hobbs and others began championing more primary care experience for MCG’s 180-member student body, the conversation struck a note with Wilson, who already knew the capabilities of his colleagues throughout Georgia.

Wilson became a sort of human litmus test for identifying strong primary care physicians in the vast state who could and would help teach MCG students. “Dr. Wilson said we needed to put this clerkship out where the physicians are, and he was right. He understood the importance of students getting experience in a wide variety of clinical settings and, in a state such as Georgia, that includes our more rural areas,” says Dr. Joseph W. Tollison, then Chairman of the MCG Department of Family Medicine. Critical to the success of the clerkship, says Tollison, was its coordinator, Libby Poteet, who strategically managed the program during its first 20 years.

“We were late to the process,” says Hobbs, noting that family medicine programs in other states already had decentralized family medicine clerkship networks. Tollison often went along as Hobbs, Wilson, and Poteet combed their state, where family medicine physicians in cities such as Columbus already showed their teaching might with residency programs. They visited physicians such as the late Dr. Ollie O. McGahee Jr. (’58) in Jesup, whose practice was already experimenting with electronic medical records; Dr. Lanny R. Copeland in Moultrie, the first Georgia physician to lead the American Academy of Family Physicians, who would later help train family practice residents at Phoebe Putney Health System in Albany; Dr. Larry Boss (’61) in Villa Rica, west of Atlanta; and Dr. Jonathan Reimer (’78), practicing in MCG’s hometown. Hobbs still shakes his head at the exceptional practices Wilson steered them to. It was a big job.

Cultivating Relationships

Tollison took what Hobbs considers a strategic move of waiting until the clerkship network could be done right, despite political pressure to get it done now. Tollison also gave Hobbs, Wilson, and others the space to be entrepreneurial, a true gift of leadership, Hobbs says, that he has tried to emulate.

Long before the electronic heyday, they digitally linked their new teaching sites so students learning in those areas would have ready access to MCG resources. To gauge their progress and stave off naysayers, they meticulously collected student feedback, data that would later be used to establish national guidelines for clerkships. Today, MCG has 25 family medicine clerkship sites across Georgia, as well as five additional sites in the Athens area started by the GRU/UGA Medical Partnership campus.

When the nearby rural counties of Warren, Glascock, Taliaferro, and Hancock found themselves without a physician, Wilson paired with Hobbs and other faculty members again to cultivate a mutually beneficial relationship with Tri-County Health System Inc. The 30-year-old initiative to treat the medically underserved became a strong referral site for MCG subspecialists, and until recently, Tri-County also served as a teaching site for students and residents. Hobbs was on the phone on a recent day working to re-establish the important relationship.

He directed the family medicine clerkship for 18 years with institutional funding and has continued for nearly 25 years with additional support from the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration. The Georgia Board for Physicians Workforce and HRSA also help support the family medicine residency program.

Widespread Recognition

Hobbs became the department’s Vice Chairman of Academic Affairs in 1993, was elected President of the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine four years later, and was named Interim Department Chairman in 1998, when Tollison left to become Deputy Executive Director of the American Board of Family Practice (now the American Board of Family Medicine). Later that year, he was named Chairman, a title that includes holding the Georgia Academy of Family Physicians Joseph W. Tollison, MD Distinguished Chair (now Distinguished University Chair).

His tenure has also included chairing the Academic Family Medicine Organizations Subcommittee on Predoctoral Education, serving as Senior Associate Dean for Primary Care and Community Affairs, and serving on the Association of Departments of Family Medicine Board of Directors and the Pisacano Leadership Foundation Board of the Philanthropic Foundation of the American Board of Family Medicine Inc. He received the 2002 Thomas W. Johnson Award for contributions to family medicine education from the American Academy of Family Physicians and was named MCG Senior Associate Dean for Faculty Affairs and Primary Care in 2013.

At home, his department had begun implementing Patient-Centered Medical Homes to help the faculty optimize access, quality, and continuity of care. (See Spring 2013 edition of MCG Medicine). The homes remain under constant renovation as the faculty continuously assesses issues such as how often patients should be seen and how to optimize those visits.

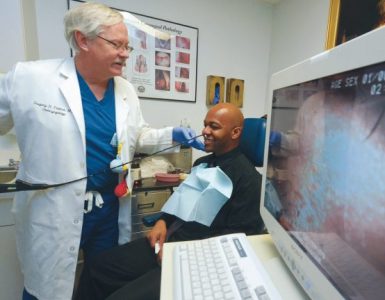

Attention to Detail

“I can’t take care of you, your chronic health problems, and preventive-care requirements in a 15-minute time slot, and we are fooling ourselves to even remotely think we can,” Hobbs says. So he and his colleagues are upping the game on every person who interacts with a patient: from the nurses who take vital signs and draw blood to staff members who communicate with patients between and during appointments. Efforts are ongoing to optimize patients’ wait time as well. In 2010, MCG’s family medicine department became the first academic health center-based practice in Georgia to be recognized as a medical home by the National Committee for Quality Assurance.

Hobbs’ unyielding efforts to advance the front-line discipline that now roars in his belly earned him the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine’s 2007 Recognition Award and 2010 President’s Award. Most recently, he’s been visiting nearby colleagues interested in increasing family medicine residency offerings in Georgia. He sees a problem that simple physician redistribution – if it were possible – would not fix. Growing the entire physician population is likely needed to fix primary care deficits but may yield surpluses in some subspecialties, he reasons.

Currently, his department and GRHealth are training 24 residents and have federal approval, but not funding, for 36 in the 42-year-old residency program. Addressing the shortage will require more than additional funding because of 21st-century realities including a reimbursement system that pays more for procedures than minutes spent in conversation, doing comprehensive exams, and managing patients’ health care needs. Another issue is the desire of many young physicians for a better work-life balance.

Hammering it Home

“Quite frankly, we are going to have to work on different systems of primary care in order to address the issue of work-life balance,” says Hobbs, citing this as one priority in his newest roles as President-Elect of the Association of Departments of Family Medicine and President of the Georgia Academy

of Family Physicians’ Educational Foundation. Many common issues gnaw at his colleagues across the state and nation. More than 40 years after family medicine departments began nesting in academic health centers, signs persist that third-party payers aren’t the only ones who underestimate their value. Primary care physicians are the referral source for subspecialists and departments such as Hobbs’, which handles about 35,000 patient visits each year, refer 98 percent of their patients to MCG subspecialists as needed.

“We try to be the primary care voice of our enterprise, to let [the administration] know how valuable we believe we could be to an effective health care system and to the success of the entire academic health center,” Hobbs says. “Patients are sunk; referrals are sunk without primary care. You have to build your primary care base, so we take every opportunity to hammer that home over and over again.” That advocacy role is important modeling for students and residents as well, he says.

Conceding that it doesn’t have to be family medicine making the primary care noise at his home base and beyond, Hobbs enjoys the rumble as he respects the decorum, much as an amalgam of his mom and dad might.

Beside Every Good Man

Dr. Joseph Hobbs leaves his rumble side at the office because he goes home to Janice Polk Hobbs.

They met in high school, and his take is that Janice, two years his junior, was absolutely not interested in him. “She was too glamorous for me,” he reflects. After nearly 40 years of marriage and three children, he describes her the same way today, no doubt with the same smile spread across his face.

As he was off rabble-rousing at Mercer, she was training to become a language arts teacher, first at Talladega College in Alabama, then at the University of South Carolina. Both came home to Augusta. Like many things in Hobbs’ life that at first glance seem coincidental, it turned out that James Polk, Janice’s brother, was working at the hospital when Hobbs was a medical student. Hobbs would sometimes stop by. James one day suggested that Hobbs reach out to his sister and Hobbs, confident in many settings, nervously did so. He found the young educator articulate, smart, challenging, interesting, and apparently “somewhat” interested in him. They married six months after he finished his residency. “She was convinced I was going to be a working man,” he says.

Not unlike his parents, Hobbs and his wife are very different people, but it works. His biggest joy has been watching her with their children. “I think that, as much as I love my children, she is probably a far better parent than I have been. She really mixes it up with them,” he says, inspiring them to be involved and competitive in their niches. That also appears to have worked.

Son Reginald, who graduated from Mercer in computer sciences, earned an MBA at Georgia State University and works as a computer analyst. Daughter Tiffany, an actress, is a University of Georgia graduate in theater and public relations and has a master of fine arts degree from Southern Methodist University. The youngest, April, earned a biology degree at UGA and a master of clinical sciences degree at Mercer. She is now a student at MCG.