A new endowed chair named for Dr. William S. Hagler recognizes the work of the MCG graduate and retina and vitreous surgery pioneer.

The mahogany case holds all the tools a Civil War surgeon would need – engraved saws for amputations, wicked-looking trephines to bore holes in skulls, slender hemostats and even more delicate scalpels.

Compared side by side with modern surgical equipment,

it could have hailed from the dark ages – something

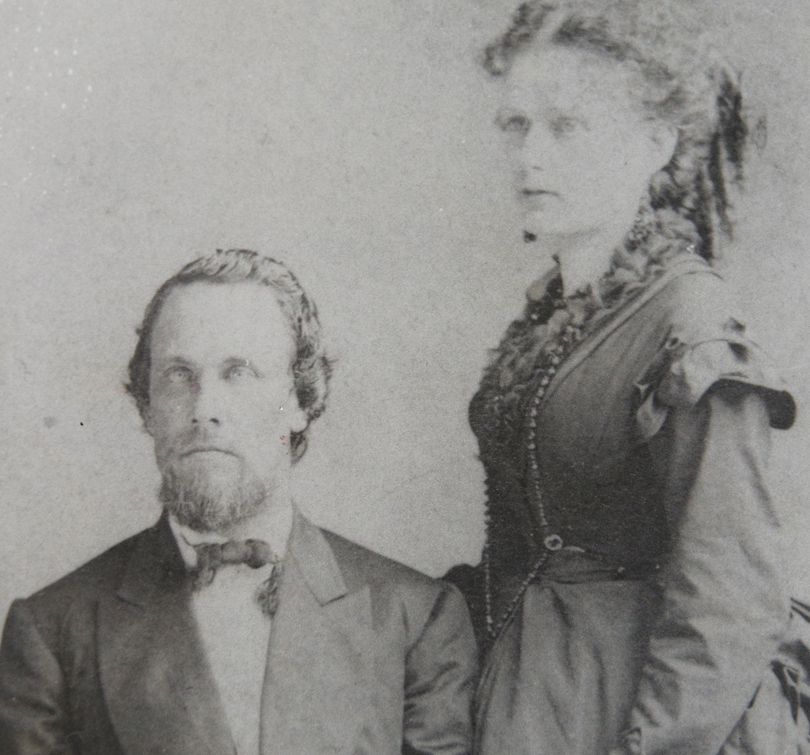

Dr. William S. Hagler (’55) often reflects upon when he opens the Civil War surgical kit belonging to his great grandfather Dr. Thomas Burdell, who had graduated from MCG about 100 years earlier than him and was wounded in the battle of Bull Run.

The comparison is apt as it mirrors the rapid changes that have occurred in ophthalmologic surgery since the late 1940s, a transformation that Hagler both witnessed and contributed to in his own 40-plus-year career as a retina/vitreous surgeon and teacher.

From the Cornfields

Little Billy Hagler would often look across the cornfields of 15th Street from his grandmother Katherine Hagler’s house to gaze at the Medical College of Georgia and its affiliated University Hospital. The impressionable young boy knew early on he’d be a student there. Like his great-grandfather, his uncle Dr. Irving Phinizy and cousin Dr. John Phinizy were also graduates, and throughout his growing-up years, the medical students who roomed at his grandmother’s spacious home encouraged him to become a physician. His cousin,

Dr. Mary Anne Hagler, was a graduate too – the oldest graduate ever and at the top of her class of 1975, the family says.

Despite being “spooked” on his first day at MCG by row upon row of cadavers in the anatomy room of the Victorian-era Newton Building, Hagler excelled at medical school and graduated with honors. They were, as he describes it, “the good old days,” when “we medical students did things they don’t do today – we delivered babies ourselves and assisted in surgery…We acted like interns and nurses, and it was good for our training.”

That broad base of clinical training stood him in good stead when he moved on to an internship at Parkland Hospital in Dallas and then an ophthalmology residency at Emory University School of Medicine and Grady Hospital. Surprisingly, recalls Hagler, ophthalmology was a “last-minute” choice – he’d been exposed to it during his rotating internship at Parkland, which covered every major field of medicine, but “I wasn’t in love with it.” In fact, he’d been accepted to become a U.S. Air Force flight surgeon. Still, when faced with two good choices, Hagler decided on ophthalmology.

It would turn out to be the right choice.

Modern Medicine

“I was very lucky to be born when I was born,” says Hagler. “If I had been born 20 years later, I wouldn’t have had the opportunity to be at the beginning of a whole new field, and if I had been born 10 or 20 years before, I would have been too old. I was just lucky that I came along at the right time and had the right teachers.”

At Emory, similar to MCG, Hagler and his fellow residents worked very closely with faculty members and enjoyed rich and variable clinical experiences. “But looking back, there was very little an ophthalmologist could do then as compared to now,” says Hagler.

Cataracts could be removed “in a fairly dangerous way,” with the patient requiring five days of hospitalization and thick glasses thereafter. Surgery was available for children with crossed eyes and rudimentary surgery and drops for glaucoma. “There was no treatment for retinal detachment, diabetic retinopathy or even eye infections inside the eyes,” says Hagler. “It just absolutely stymied me. I thought, ‘There have got to be some answers to some of these problems.’”

One answer lay just over 1,000 miles north of the Peach State with Dr. Charles Schepens, a Belgian ophthalmologist who immigrated to the United States in 1947 and had invented the modern binocular indirect ophthalmoscope just two years prior. “That instrument enabled us to see the entire retina for the first time in history,” says Hagler.

Schepens brought that knowledge with him to Boston and the Eye Research Institute at the Retina Foundation, part of the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary at Harvard Medical School. There, he would establish the world’s first retina service and retina disease fellowship.

“Ophthalmology [then] became the fastest-growing field in all of medicine,” says Hagler. “It just exploded shortly after I finished residency.”

The modern invention with its three-dimensional view of the retina enabled ophthalmologists to diagnose tumors, other elevated growths and retinal tears. It revolutionized treatment of detached retinas, when the only result for patients prior to the ophthalmoscope was to simply go blind. “It also enabled us to study so many other diseases of the body that become manifest first in the retina. Common ones are diabetes and high blood pressure, but there are numerous other rare and exotic systemic diseases, such as AIDS, fungal and parasitic diseases,” says Hagler.

Hagler knew he had to learn how to use this new instrument. He was one of six ophthalmologists in the country to be awarded a Heed Ophthalmic Fellowship, which allowed him to spend a year in Boston working with its inventor. Under Schepens’ guidance, Hagler spent thousands of hours practicing how to use the ophthalmoscope, both in diagnosis and surgery. The device requires the practitioner to wear the instrument on the head, while holding a lens in one hand and other instruments in the other. Another challenge was teaching the brain to reorient the image, since the ophthalmoscope presents the retina upside down and backwards. “Picture trying to learn to play the piano or build a computer through a mirror,” says Hagler, “yet we have to perform surgery this way.”

Twelve months later, Hagler was back at Emory, the first full-time faculty member in ophthalmology and the first in the Southeast outside of Miami to offer training in the basics of retina and vitreous diagnosis and surgery. “We had fun,” says Hagler. “I hate using that word when you’re talking about medicine, but it was fun being part of a new and exciting developing area of medicine.”

An Evolution

Together with his partner Dr. William Jarrett, Hagler would focus the remainder of his career on improving and developing new techniques to make retina and vitreous surgery safer and more effective, while also performing clinical research on unusual eye diseases.

At conventions such as the American Academy of Ophthalmology, Hagler and Jarrett would teach their techniques for using freezing cryotherapy technology along with various types of silicones to treat retinal detachments. “We found it reduced the rate of complications significantly and increased the success rate,” says Hagler. They also were pioneers in using radioactive phosphorus to greatly improve the accuracy of diagnosing malignant melanoma of the eye.

A related new field of interest was laser surgery, which was meticulous, allowing the surgeons to seal retinal tears before a detachment occurred, as well as help prevent blindness from diabetic retinopathy and macular degeneration.

While they played a role in the development of retina surgery, Hagler and Jarrett were among the first surgeons to employ endoscopic techniques for vitreous surgery, using tiny needles and instruments under direct microscopic vision – no more mirror images – magnified at least 50 times. “That means the human hair looks like a finger,” says Hagler.

More exotic eye diseases that captured his attention included toxoplasmosis and histoplasmosis. He and Jarrett were also the first to discover the link between Stickler syndrome – a genetic condition that can cause certain facial abnormalities, including cleft palate – with a severe form of retinal detachment. They were able to identify hundreds of patients throughout the Southeast with this dominant gene and help prevent them from going blind. As a result of their work, Hagler and Jarrett published about 70 peer-reviewed articles in the major medical journals.

Hagler did all this while continuing to share this knowledge with what would become hundreds of residents and fellows – he and Jarrett established the first retina and vitreous fellowship in the Southeast – throughout the years. This included serving as a clinical associate professor in ophthalmology at MCG and teaching residents during their three-month rotation in Atlanta. One of those residents was Dr. Julian Nussbaum, who would later become Chair of the Department of Ophthalmology and Director of the Retina Service at Augusta University Health. “He was an excellent surgeon like me, and he fell in love with this field,” says Hagler. “He went to the same place [Boston] to study under Dr. Schepens a good many years after me to become a retina and vitreous specialist.”

Several more years after that, Nussbaum would return the favor by presenting an endowed chair, named in Hagler’s honor, to support the academic mission of the Department of Ophthalmology at MCG, including the teaching of medical students, residents and research fellows. It will also bring internationally renowned clinicians and scientists to MCG and to Augusta University and support pilot programs in vision science through the university’s James & Jean Culver Vision Discovery Institute.

Hagler has contributed to the chair, with a matching donation by the MCG Foundation, and trainees, friends and families have raised the remaining amount. “It makes me feel very good, very humble and honored to use my name for that,” says Hagler.

Once again, the timing just seems right. “I really appreciate the fact that when I went to MCG, the focus was on teaching me to be a clinical physician,” says Hagler. “And I have always thought that MCG had a major interest in training physicians to go out into the community and practice clinical medicine…I know I appreciated getting that training when I became an intern and a resident – much more exposure to clinical training than a lot of other fellow interns and residents. I’m hoping this endowment will help continue that focus.”