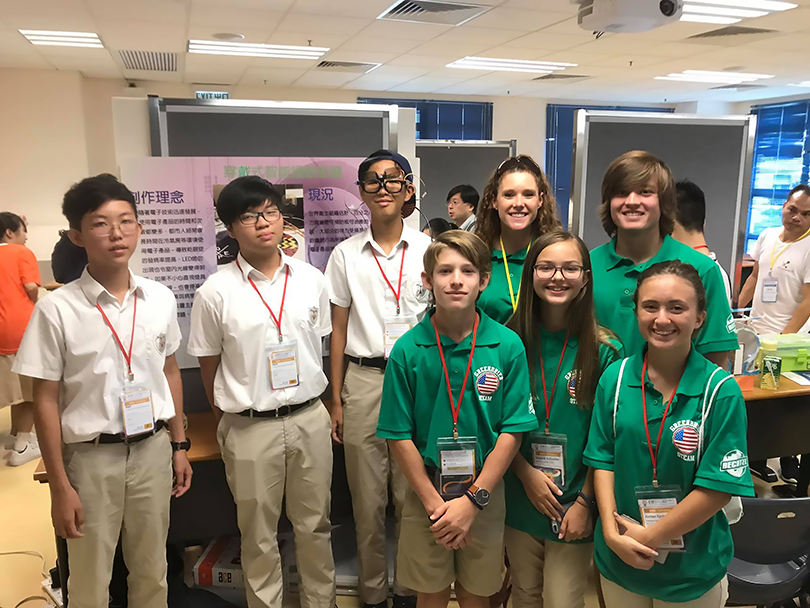

David Phillips (EdS ’10) knew he and his team of six seventh graders would be facing a lot of challenges when they agreed to go to Lingnan University in Hong Kong to compete in the International Young STEAM Maker Exhibition — you don’t fly halfway around the world and expect things to be easy — but he didn’t realize just how insurmountable those challenges would seem until he and his team arrived at the competition venue.

There, amid the crush of other teams — from Hong Kong, mainland China and Malaysia — they got a taste of the types of projects they would be up against. Things like a 5-foot-tall metal recycling robot and an entire city built out of electronics and laser- cut wood.

Things that had obviously been built over a time period much longer than the month or so they themselves had been given to prepare.

Project intimidation wasn’t the only thing conspiring against them, however. For one thing there was the language barrier, which isolated them from competitors, organizers and even the judges.

As the only Americans, that was more or less expected, at least to some degree, but something they didn’t expect — and had to adjust to on the fly — was the fact that the five-minute presentation they had prepared for and rehearsed for and knew inside and out was, in fact, a three-minute presentation. And it wasn’t just the fact that they had practiced for five minutes — they had five minutes’ worth of PowerPoint slides as well.

So with everything against them, it seemed certain Team USA — the six kids from Greenbrier Middle School in Evans, Georgia — had traveled all that way to be also-rans, fodder for the teams that had more time, more understanding and more working in their favor.

But if you know anything about competition — and make no mistake, this wasn’t an excuse for sightseeing, this was a competition — you know that Yogi Berra got it right when he famously said,

“It ain’t over till it’s over.”

Building Success

Mr. Phillips’ Greenbrier Middle School STEM competition team — STEM stands for science technology engineering and math — was formed at the beginning of the 2018-19 school year. Spinning out of his applied research and problem solving (ARPS) class, the goal for the small, tight-knit group of students was to understand how to analyze a complex engineering problem and work together to develop an engineered solution.

Mr. Phillips’ Greenbrier Middle School STEM competition team — STEM stands for science technology engineering and math — was formed at the beginning of the 2018-19 school year. Spinning out of his applied research and problem solving (ARPS) class, the goal for the small, tight-knit group of students was to understand how to analyze a complex engineering problem and work together to develop an engineered solution.

“There are some students who are labeled gifted or accelerated and some who are not,” Phillips says of the team. “But one thing they all have in common is that they’re very competitive, and they want to be challenged.”

In fact, the students were so motivated that class time proved insufficient; they told him they felt they needed to start meeting after school.

“If they said, ‘We’re just not ready — we need to stay after school or do this or that’ — I just made myself available,” he says. “It takes what it takes to get it done.”

The team kicked off its competition season at Augusta University’s MindFrame STEAM competition last October (the “A” added to STEM stands for arts and is sometimes used to broaden the scope of the education model).

There, the team designed, built and launched a rocket powered by water pressure.

The payload: A chicken egg.

The landing zone: An area 30 feet in diameter.

The result: The team won the competition’s overall grand prize for middle school engineering.

In the spring, they entered the U.S. Army’s eCybermission competition, where the students won first and second place in Georgia, placed in the top three in the Southeast region and won $8,000 in college scholarship money.

In the spring, they entered the U.S. Army’s eCybermission competition, where the students won first and second place in Georgia, placed in the top three in the Southeast region and won $8,000 in college scholarship money.

Not bad for a fledgling program at a school without an established STEM education program, but maybe not all that surprising, given Phillips’ track record as an educator.

Return of a Leader

A graduate of the University of Georgia, Phillips earned his education specialist degree at Augusta University, something he credits for his ability to create STEM challenges.

“My education specialist degree in curriculum and instruction really allowed me to take the next step as far as being an educator,” he says. “I learned how to not only do great lessons in the classroom, but how to write my own curriculum and come up with programs in a class that I design.”

This led him to create his STEM program, which he built more or less on his own.

“I think my time at Augusta University really helped with that,” he says. “It gave me a lot of confidence to take risks and assume leadership roles within a curriculum. That’s when I started getting into learning about STEM and going to STEM conferences and really trying to give the students these experiences outside the classroom.”

All the attention that came from the team’s good showings — not to mention his Teacher of the Year award and being named a finalist for Columbia County Teacher of the Year* — represents a high-profile return of sorts. Before leaving the area to teach in Nashville, Tennessee, Phillips spent 11 years at Evans Middle School, where he engaged his students with similar science-based challenges, including one that ended up with him taking two teams of students to Huntsville, Alabama, for a week at NASA’s Space Camp. There, the students presented to a NASA panel that included one of the designers of the lunar rover.

Oh, he won Teacher of the Year at Evans, too.

“One thing I learned that stays with me to this day: Kids that age can do really difficult stuff,” he says. “It’s hard to go back to staying inside the walls of the classroom once you’ve done stuff like that.”

So when he returned to Columbia County in 2018 and started up at Greenbrier Middle School, he was primed, though not necessarily expecting, to once again vault outside the boundaries of the traditional classroom.

“I really had no plans of creating a STEM program; it’s just this opportunity came along,” he says. “The students were there, and they kept begging for competitions and challenges, and you just have to give it to them.”

There are challenges, however, and then there are challenges, and when Dr. Ashley Gess, who ran Augusta University’s MindFrame competition, sent Phillips an email asking if he’d be interested in taking students to the International Young STEAM Maker Exhibition in Hong Kong, he literally had no idea what he was getting into.

Opportunity of a Lifetime

“It was a very cryptic email,” Phillips remembers. “’I have an opportunity we need to discuss — call me.’ And when she told me, I couldn’t believe it.”

Not long after the MindFrame competition, Gess, who is an assistant professor of STEAM education in the College of Education, had been invited to Hong Kong to train faculty members in STEAM education, and while there she met up with Dr. Xiangong Wei, a representative from Lingnan University, who was heading up the STEAM Education and Research Center. Later, he invited her to be a judge and keynote speaker at the International Young STEAM Maker Competition in July.

For Gess, adding the arts to the mix — something not universally applauded — is all about inclusion.

“The whole thing is about designing and implementing a solution to a problem, and the design process is where the robust activity happens,” she says. “But if you only allow them to realize their process in engineering or technologies, you’ll still lock out a group of people.”

More than 600 students from Georgia and South Carolina signed up to compete in the MindFrame STEAM competition, which has been named STEAMIFY moving forward. Gess hopes to bring 3,000 in its second year, and while learning opportunities for the students are obvious, Gess views it as a chance to move the needle on education in general by exposing teachers to this philosophy.

“I think we’re already realizing some of the effects of last year’s competition,” Gess says. “This year we have 75 teachers in our STEM endorsement.”

The STEM endorsement is a graduate-level achievement that works like an add-on to the STEM certification. It teaches the concept in a formal setting rather than in the informal setting of the competition.

When Wei approached Gess about attending the Hong Kong competition, he told her he was also interested in having participation from the United States — so much so that he was willing to pay for about 80 percent of the team’s travel costs.

“I really couldn’t believe it,” Phillips says. “Being able to take some of the cost off really let us open the door to present it to them.”

Phillips wasn’t the only one who had trouble believing.

“When Mr. Phillips first told me, he began his speech with, ‘This is not a joke,’ but when he said it, I still thought it was a joke,” says 13-year-old Kendall Schneller. “It didn’t really hit me until we got off the plane that we’re in Hong Kong.”

“When my wife texted me, I thought it was a typo,” says Matt Forshee, whose daughter Emily also competed in Hong Kong.

Hong Kong is 12 hours ahead of Augusta, so the delays in getting questions answered complicated things, as did the fact that all this planning and trip preparation was basically going on during the last two weeks of school.

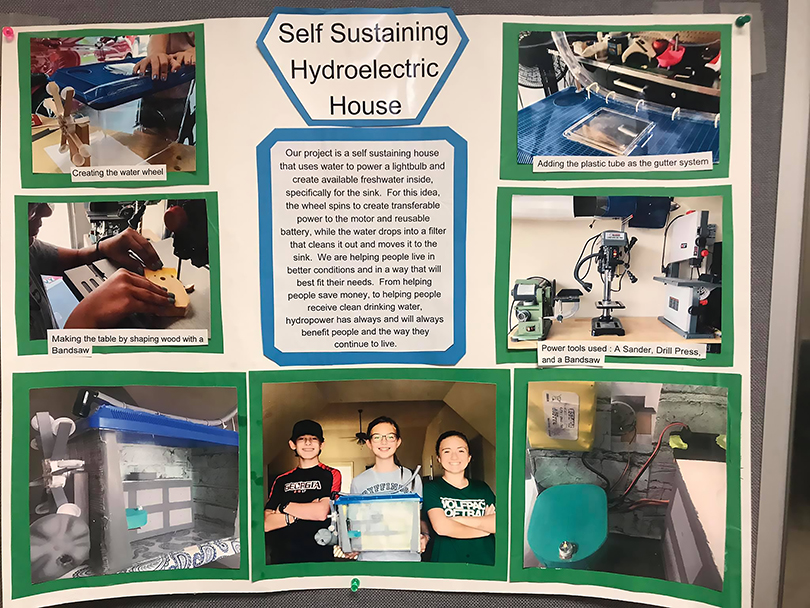

Like the MindFrame STEAM competition, the Hong Kong competition had several components. Teams created a project — one group worked on a maglev car, the other a self-sustaining house that used rainwater to generate electricity — but students would also be randomly split up into groups to solve a spontaneous problem. And at the 11th hour, even Phillips was thrown into the mix when he was informed of a competition for teachers.

“And I thought I had enough to worry about on this trip besides a teacher competition,” he jokes.

Still, you don’t lead a bunch of achievement-minded kids on a trip halfway around the world if you’re the type to shy away from challenges of your own; of course he said he’d do it.

Representing the Nation

So the early summer was a whirlwind of project development and fine-tuning, all with a wary eye to the nightly news, which frequently began with stories about the pro-democracy protests that had erupted throughout Hong Kong and showed no sign of letting up.

And though most of the kids were experienced travelers and several were joined by their families for this rare and exciting opportunity, the logistics of the trip itself were daunting. Fifteen hours in the air, 33 hours door to door. But with a day to unwind and sightsee before the competition — and outfitted with Team USA shirts — Phillips and the team felt pretty good about their chances … until that moment when they encountered the incredible recycling robot, the audacious electronic city and all the other projects that looked so formidable.

And though most of the kids were experienced travelers and several were joined by their families for this rare and exciting opportunity, the logistics of the trip itself were daunting. Fifteen hours in the air, 33 hours door to door. But with a day to unwind and sightsee before the competition — and outfitted with Team USA shirts — Phillips and the team felt pretty good about their chances … until that moment when they encountered the incredible recycling robot, the audacious electronic city and all the other projects that looked so formidable.

“Our kids had about a month to prepare, and when we got there we found out that other teams had pretty much invested three, four, five months in their projects,” Phillips says. “And keep in mind, our projects had to fit in a suitcase.”

And then came word that they had three minutes to present, not five. Not only that, but only one of the three judges spoke — maybe — a little English.

Even Phillips’ presentation ended up being shorter than he had been told to prepare for.

“It was definitely pep talk time,” Phillips says.

Pep talk or not, with less prep time than the others, less presentation time than planned and no confidence that any of the judges could even understand them, Phillips’ plucky 13-year-olds seemed doomed to fail, beaten down before they even had the chance to perform.

Even Gess, a familiar face, was too busy with her duties as speaker and judge to offer much more than moral support.

Fifteen hours in the air to go through the motions. Thirty-three hours door to door to be also-rans.

All in all, an 8,500-mile bust.

“At that point, they felt they were just going to have a good time,” Phillips says. “They knew they weren’t going to get anything.”

But if STEM and STEAM teaches students anything, it’s the confidence that comes from being prepared. After all, wasn’t engineering a solution to a problem the point of it all?

And so that’s what they did. They cut slides; they adjusted their presentation; they convinced themselves it didn’t matter if the judges could understand them or not since their slides were translated anyway; and they delivered.

The result?

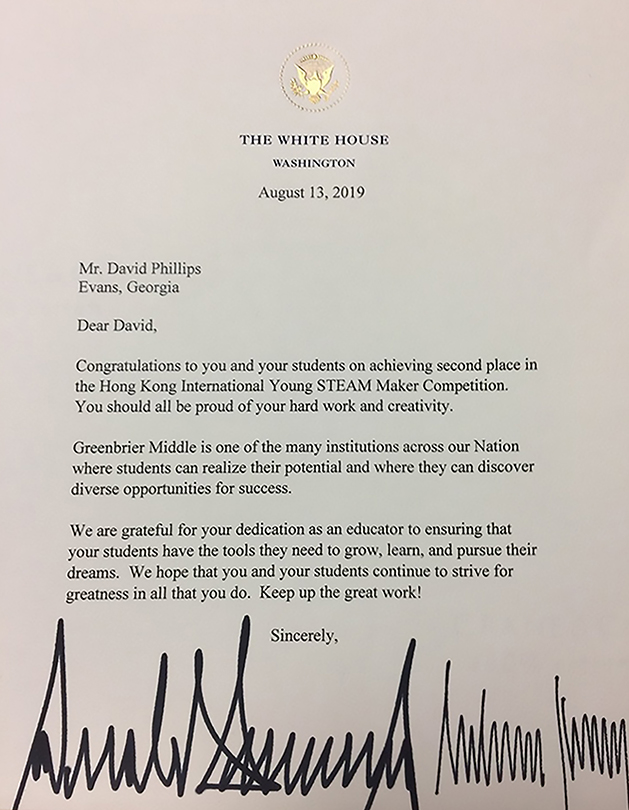

Greenbrier Middle School left Hong Kong with three second-place finishes and a third; Phillips won second place in his competition; and out of the 111 teams entered in the competition, they won second place in the overall STEAM Maker exhibition.

“Number two in the world,” Phillips says. “It has a good ring to it, doesn’t it?”

A few weeks later, Phillips even got a letter of congratulations from the White House — something Gess finds particularly rewarding.

“Regardless of what we think of the person, yea or nay, it’s the office, and that’s important,” she says. “And I’m thrilled, because that’s our job here at the College of Education — to lift up teachers.”

“Regardless of what we think of the person, yea or nay, it’s the office, and that’s important,” she says. “And I’m thrilled, because that’s our job here at the College of Education — to lift up teachers.”

But no matter how many accolades, Phillips makes it clear that second in the world is not an end, but a beginning.

“What better way to prepare for life in some field or industry with people of diverse backgrounds and faiths and whatnot,” he says. “And when they’re doing it at 13 years old — and at an international level — they’ve got a huge jump on leadership skills and problem-solving skills.

“They’re going to be pretty amazing one day,” he concludes with a smile. “They already are.”

*Phillips was named 2019 Columbia County Teacher of the Year in early October