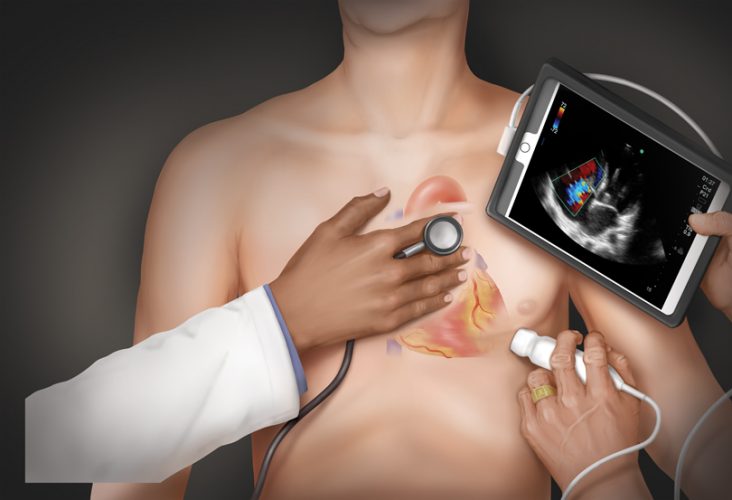

Ultrasound: “The 21st Century Stethescope”

Its beginnings can be traced to the late 1700s, when a physiologist named Lazzaro Spallanzani first studied how bats use the reflections of sound to find things.

More than 200 years later, ultrasound is being called “The 21st Century Stethoscope,” and it’s changing how the Medical College of Georgia teaches future physicians and how its health system provides patient care.

Ultrasound works by using a probe to transmit high-frequency sound waves into the body, collecting the bounced back waves and feeding them to a computer to create immediate images of tissues and organs.

At the state’s public medical school, it’s giving students an in-depth and novel look at the organ systems they’re studying during their first two, basic science intense, years of medical school, and new and faster ways to enhance learning physical diagnosis in their clinical years. At patients’ bedsides, the use of ultrasound is also changing health care delivery by allowing MCG physicians to make important clinical decisions right there, often without expensive and unnecessary tests.

Ultrasound that fits in your pocket

The technology is not new – the first time it was used to make a medical diagnosis was the mid-1940s – but it has only been in the last decade or so that ultrasound machines have become portable without losing the benefit of good image quality.

That development is what initially piqued the interest of Dr. Paul Wallach, MCG’s former vice dean for academic affairs who is now executive associate dean for educational affairs and institutional improvement at Indiana University’s School of Medicine.

“The old ultrasound machines were big – the size of washing machines,” Wallach remembers. “What I saw happening in the world though was the technology was starting to get better and smaller, a lot like what happened with computers and cell phones. They became smaller and smaller than ever and less and less expensive.”

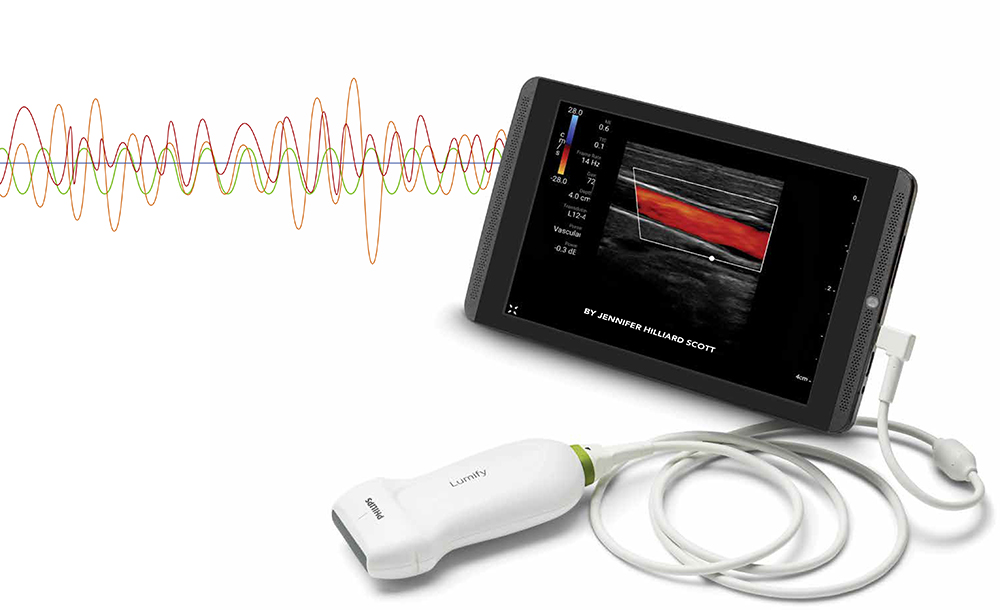

Today, he says, anyone can purchase a handheld ultrasound machine that produces high quality images and hooks into a tablet that fits in the pocket of a white coat, all for under $5,000. “What does that mean?,” he ponders. “Five years from now, it’s going to be smaller, it’s going to be Bluetooth compatible, and it’ll be quite affordable. That means that every health care provider is going to end up with them in their pocket. If that’s the vision and you see that happening, what’s our responsibility as an educational institution? To teach doctors how to use it.”

And do it now.

Wallach began thinking of ways to integrate ultrasound into the already crowded undergraduate medical school curriculum shortly after he arrived at MCG in 2012.

Just before Wallach’s arrival, the Augusta University College of Allied Health Sciences announced the closure of its bachelor’s degree level sonography program. In the meantime, its program director Becky Etheridge, was enrolled in a teaching scholars fellowship at MCG’s Educational Innovation Institute.

As fate or luck would have it, the co-director of the fellowship, Dr. Chris White, an emeritus professor of pediatrics who still teaches MCG students physical diagnosis, had been reading about the Stanford Medicine 25, a list of 25 physical exam skills the Stanford University School of Medicine thought every medical student and resident should master before treating patients.

Number 20 on the list was bedside ultrasound.

It was like the perfect storm.

“(Dr. Wallach) met with me and told me that he wanted to offer point of care (or portable) ultrasound through the medical school curriculum, and that they were going to bring me on as an instructor to do that,” Etheridge remembers. “And what he told me that day in 2013 has been exactly what we’ve done. We’ve never strayed from that. We’ve only expanded it.”

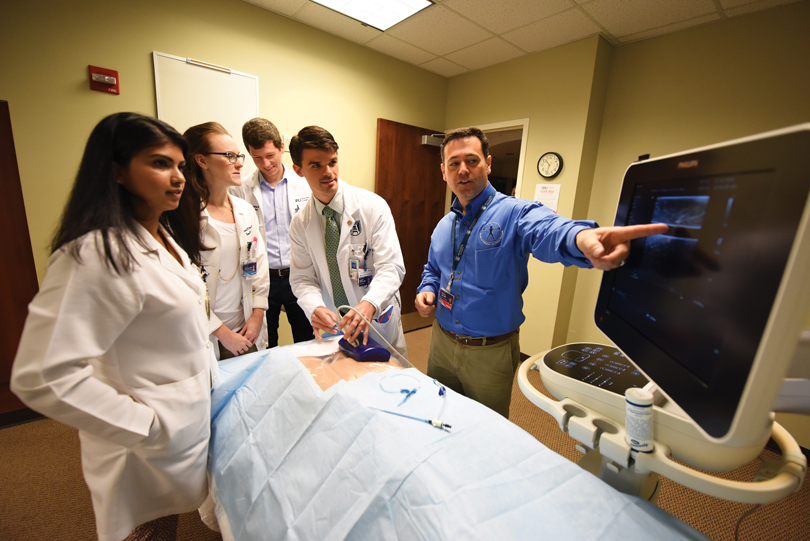

Once hired, and over the next year, Etheridge set to work laying out a way to integrate ultrasound into the first and second years of medical school. She also had to acquire the necessary equipment – ultrasound machines, high-fidelity simulators and phantoms, specially designed objects that produce ultrasound images when scanned – to teach the 190 medical students per class at MCG’s main campus in Augusta.

The system she and Wallach developed offers, in the first year, ultrasound labs that correlate to the modules students are studying in class and in the gross anatomy lab. For instance, if the students are studying the musculoskeletal system, ultrasound labs are focused on scanning anatomy like shoulders and knees. In the second year, ultrasound labs correlate to skills and organ systems students are simultaneously learning in physical diagnosis workshops.

“Ultrasound is the cognitive scaffolding for the learning of the adjacent basic science,” Wallach says. “We use these labs to reinforce anatomy, to reinforce pathophysiology. It makes clinical medicine come alive.”

“It was very helpful for me to see in an ultrasound image the same structures that I was putting my hands on in the anatomy lab,” says fourth-year student Tahira West, who now helps teach more junior medical students in ultrasound labs. “Often, the hardest part is understanding the orientation of the anatomy in a living, breathing human being – what is posterior, anterior, for example. It’s difficult. Take the cardiac exam. The heart kind of sits diagonally in a sense. Seeing an ultrasound image of that helped me understand the anatomy better, helped me understand what I was looking at.”

For two years, and mostly as a lone wolf, Etheridge taught ultrasound labs to first- and second-year medical students in the Interdisciplinary Simulation Center in the J. Harold Harrison, M.D., Education Commons. But Wallach and she both knew the curriculum needed to expand to the third- and fourth-year clinical clerkships.

They found the perfect partner to help in Dr. Matt Lyon, a 1999 MCG graduate and vice chair for academic programs and research in the Department of Emergency Medicine.

Overcoming sound barriers

Back during Lyon’s residency at MCG, the department had developed a fledgling ultrasound training program. While the program had a lot of stops and starts, Lyon says he knew how important and useful a tool ultrasound could be to emergency medicine physicians. He had seen it in action – being used for things like quickly diagnosing fluid on the heart, a life-threatening pneumothorax, detecting gallstones…the list goes on.

He began compiling thousands of ultrasound images and videos he had and used them to develop a lecture series he could use to teach emergency medicine residents how to use ultrasound.

“I went all around the Southeast teaching people how to use ultrasound at the bedside,” Lyon remembers. “Anyone who would let me come and teach a course, I would do it.”

But more than teaching emergency medicine physicians and residents how to use the technology, his time on the road taught Lyon important lessons about helping people get over self-imposed barriers to using ultrasound. “I was teaching people who had never used the technology. I had to help people overcome their initial shyness and reluctance,” he says. “There’s always some of that with a new skill because they’re afraid they’re going to mess it up. You can’t mess up an ultrasound scan. This is a non-invasive look inside the body.”

Back at MCG, in addition to emergency medicine residents, he still worked on an informal basis with several of the medical school’s graduate medical education programs, mostly teaching handfuls of residents here and there about how ultrasound could help guide them through procedures, like placing an intravenous line. He also developed a year-long ultrasound fellowship, which he opened to graduating emergency medicine residents, and a year-long ultrasound elective for fourth-year medical students.

Knowing clinical ultrasound could and should be used across nearly every field of medicine, he began to develop an official curriculum that could translate to almost every residency program at MCG. “I designed this curriculum with the thought that ultrasound was this common language among specialties,” Lyon says. “Image acquisition and interpretation – whether the scan is normal or abnormal – is the same across disciplines. It’s how each specialty uses that information and deciding what to do with it that differs.”

For example, a scan of a patient’s leg in the emergency room that detects a deep vein thrombosis could result in different treatment than if it were discovered in the intensive care unit – but an ultrasound can be used to detect the clots in both scenarios.

Lyon began to propose his “Ultrasound 101” training to residency program coordinators across the medical school in 2015. He had nearly 100 percent buy in, and still does.

He runs regular resident ultrasound labs, focused on individual organ systems, that draw trainees in specialties from family medicine to surgery. And when new residents come on board in July, during their first week of training they all take a one-day crash course in ultrasound.

“That crash course was amazing,” says Dr. Parker Smith, a 2015 MCG graduate who is completing his emergency medicine residency this year. “On day one as a resident in the ED, you’re using ultrasound. In the critically ill, we want and need answers immediately. Is there blood in the belly? Fluid around the heart? Ultrasound can give us those answers.”

Why wouldn’t we?

The experience Lyon gained throughout his years of training residents – of convincing people what a powerful tool ultrasound was and how they could integrate it into their clinical practice – became a powerful tool to demonstrate the synergy of training residents and third- and fourth-year medical students.

“They were hearing a lot of ‘We don’t know how to do this,’ ‘It’s not something I do,’ ‘I can’t see how I can fit it into the curriculum,’ from clerkship directors,” Lyon says. “Those were the same barriers I’d already fought with residency program coordinators.”

Wallach proposed and the university’s president and its provost created MCG’s new Center for Ultrasound Education, paired Lyon and Etheridge, naming Lyon executive director and naming Etheridge director of ultrasound education. The two set about convincing clerkship directors that ultrasound had a place.

The first step was getting emergency medicine, then an elective where ultrasound was already prevalent, designated as a required clerkship. “That gave me the ability to tell people that we were already in clerkships as we looked to expand to other clerkships,” Lyon says laughing.

In 2016, students began attending labs that correlated with those resident labs, but tailored to their experience level. But Lyon, still focused on integrating ultrasound into clinical clerkships, knew if they could raise the center’s visibility, they’d be more likely to get buy in.

A course, co-designed by Dr. Steven Holsten, associate professor of surgery, using ultrasound to teach and standardize the way residents place central lines (see sidebar on page 19) that reduced the complication rates to nearly zero, did just that. “We got enough notoriety from that and momentum that when we went back to clerkships, we had visibility and credentials,” he says.

In the meantime, Wallach had found the money to purchase 20 Philips Lumify handheld ultrasound tablets, which are Android tablets with ultrasound probes attached. That meant Lyon and Etheridge could distribute the tablets to clerkship sites all over the state.

Last July, the family medicine clerkship became the first, outside of emergency medicine, to integrate point of care ultrasound into their undergraduate training. And not just in Augusta.

With the help of Dr. David Kriegel, ’98, director of medical student education for the Department of Family Medicine, and Dayna Seymore, coordinator of medical student education, the Lumify tablets and ultrasound probes were distributed to regional campuses and 28 clerkship sites in every corner of the state.

Students use the technology during their clerkships to reinforce concepts of the specialty. In the family medicine clerkship, for example, to support the national guidelines for screening patients for aortic aneurysms, students use the Lumify tablets to screen patients in the clinic. Not only are they learning the technical aspects of screening, they are also choosing the most appropriate patients who need screening.

“Why wouldn’t we introduce this to our students during their clinical training?” Kriegel asks. “This is where medicine is going. I’ve seen huge developments in ultrasound just in the last 10 years. It truly is the stethoscope of the future.”

Since the family medicine clerkship came on board last summer, obstetrics and gynecology has also added a point of care ultrasound component outside of the traditional sonography they have always used to perform fetal anatomy scans. Next year, internal medicine and surgery will be added to the mix, Lyon says.

“By this July, we will be in all of the required core clinical clerkships,” he says. “A year and a half ago, we were only in one.”

A leader in the field

Integrating portable ultrasound training throughout undergraduate and graduate medical education puts MCG ahead of the game and at the front of the pack, Wallach says.

According to Lyon, MCG is among the top one percent of medical schools using ultrasound in graduate medical education and in the top 10 percent that train their undergraduate medical students.

MCG faculty have also shared their expertise with other medical schools. Just this spring, a team from the Center for Ultrasound Education traveled to the University of Panama to teach undergraduate medical students and faculty there a compressed version of the ultrasound curriculum. What MCG students learn over four years, they taught in five days.

“This curriculum and these training programs help us attract better medical students and residents because it’s something they can’t get at other medical schools,” Lyon says. “Our students also see how we’re training residents and they want to stay, so we end up keeping the best medical students as residents too.”

“For every curricular innovation, my experience has been that there has always been a cohort of people who don’t like it and want to keep things the way they’ve always been,” Wallach adds. “I don’t think I’ve ever heard a negative comment about ultrasound. Our students appreciate that this is something that’s preparing them for their life as doctors.”

A Fluid Motion

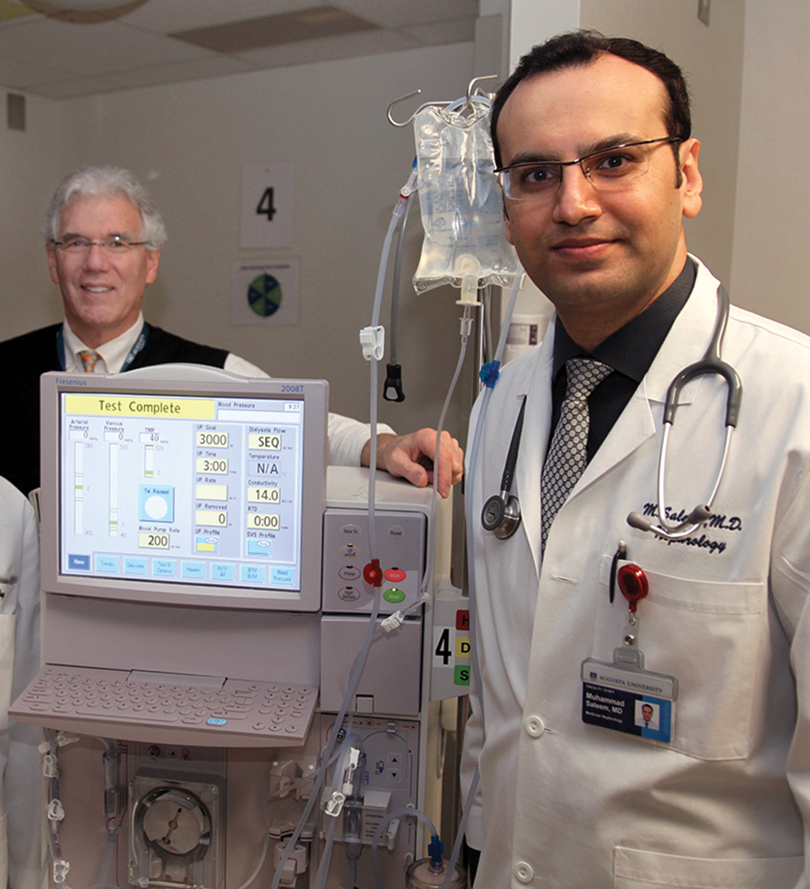

Portable ultrasound can help nephrologists better detect fluid in the lungs of patients with end-stage kidney disease, according to a study by physicians at the Medical College of Georgia.

Patients with the disease, characterized by the kidneys’ inability to work well enough to meet the body’s basic needs, can accumulate fluid all over their bodies, and commonly in the lungs, says second-year nephrology fellow Dr. Omar Saleem.

The trick is knowing where the fluid is and how much needs to be removed, Saleem says. If it’s in the lungs, it can lead to complications like heart failure and high blood pressure.

Saleem presented his research at the Southern Regional Meetings of the American Federation for Medical Research in February.

When it comes to diagnosing “wet lungs,” the standard has been listening for chest crackling sounds with a stethoscope and measuring blood pressure – more fluid on the lungs prevents oxygen from being absorbed into the bloodstream. “But that’s quite subjective,” he says. “For instance, sometimes you can’t hear the crackling. That’s why the ultrasound adds to the physical exam.”

He examined 24 end-stage kidney disease patients at Augusta University Health. As part of the normal physical exam, he placed the ultrasound probe on the patients’ chests to get a good view of the lungs. If there was fluid, he would see B-lines, which are actually reflections of the water in the lungs that appear as long, vertical white lines on an ultrasound. The higher the number of B-lines and the more intense, or bright, they were, the more fluid was present.

“This is an objective marker of lung water, the accumulation of which can lead to serious complications for already fragile patients. We’re right at the edge here and we’re trying to keep people from tipping over into heart failure,” says Dr. Stanley Nahman, MCG nephrologist and director of the Department of Medicine’s Translational Research Program. “This will change the way we manage these people with dialysis.”

Physicians can then better target dialysis treatments. “I can set the fluid removal goal at a higher point during dialysis,” Saleem says. “Where I might normally take off two liters of fluid, I might take three or four in someone who has water in his lungs.”

“Our kidneys take all the fluid that comes from normal intake through diet and drinking and they filter the waste products, which we excrete in urine,” Nahman says.

Hemodialysis uses a special filter called a dialyzer – or an artificial kidney – to filter waste, balance electrolytes and remove extra fluid.

“These patients rarely urinate. They count on dialysis to keep their fluid in balance,” he says. The kidneys also help the body reabsorb essential nutrients into the bloodstream.

End-stage kidney disease patients are typically receiving dialysis three times each week.

Technology that helps people live

Dr. Ted Kuhn’s college physics professor skipped the chapter on ultrasound, telling his class at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill that there was no real use for it.

Nearly 50 years later, Kuhn, director of international medicine in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the Medical College of Georgia, can’t keep track of the number of lives he’s helped save using the technology or the number of medical students and residents he’s trained to do the same.

His interest in portable ultrasound began in the early ‘90s when he was working as a medical missionary at a small hospital in Central America, where resources were scarce. Upon walking into his bunk, his roommate, Dr. David Hunter, introduced himself. “He said ‘I’m a radiologist and I’m really useless here, but I’ll do the best I can,’” he remembers. “Turns out, not only was he a radiologist, he was ultrasound trained. He said to me, ‘If you ever need anything, let me know.’ I told him

I wanted him to teach me ultrasound.

I trained with him for two years.”

Kuhn, who completed a fellowship in tropical medicine after finishing medical school at Pennsylvania State University, has worked for years as a medical missionary. Those early experiences helped him realize what a valuable resource portable ultrasound could be for places where resources were extremely limited. “It was a game changer,” he says. “Physicians in the developing world are mostly using physical diagnosis to diagnose disease. Technology like CT scans, MRIs and X-rays are either not available or it’s beyond people’s ability to pay.”

Realizing he could combine his training in tropical medicine and his newfound ultrasound skills, Kuhn set about using the imaging technology all over the world to better diagnose tropical diseases and alter their treatment. “It was something that was portable and something I could use to see things in people that make a life-changing difference. I have formal training in studio art. Ultrasound, for me, is dynamic art that helps people live. Instead of painting on a canvas, I paint on a screen.”

Kuhn began taking MCG students along on his mission trips, teaching them to do the same.

The MCG Department of Emergency Medicine also started to develop a fledgling ultrasound training program, but for various reasons it never really got off the ground. But in the early 2000s, an excited young emergency medicine resident named Dr. Matt Lyon, ’99, helped change all of that. Lyon, who stayed as faculty after finishing his residency in 2003, cemented ultrasound’s place in residency training.

Kuhn and Lyon joined forces and developed a curriculum to teach western physicians who are practicing in developing countries how to scan and diagnose tropical disease. For 15 years, they and other emergency medicine faculty and residents, have taught that curriculum all over the world – from Central to South America, in East and West Africa and in Southeast Asia.

“The dream is to put this in the hands of people who need it, who can save children and adults all over the world,” Kuhn says. “But it’s not just about giving them a machine. The machine can’t interpret what it scans. We want to not only put it in their hands, but also train them so they know what they are seeing. What the mind doesn’t know, the eye cannot see.”

Safety: A Central Focus

Standardized training on how to effectively place central lines using ultrasound has improved patient safety and quality of care at Augusta University Health by reducing central line complications to nearly zero in less than two years.

In September 2016, residents and fellows who insert the lines, which are placed into a large vein and used to give medicines, fluids, nutrients or blood products over a long period of time, first attended a mandatory grand rounds training session. Then they were individually tested using a cadaver model in the university’s gross anatomy lab. Those who didn’t pass had to be retrained and retake the test.

“There is always a risk associated with placing a central line,” says Dr. Matt Lyon, ’99, executive director of the MCG Center for Ultrasound Education. “And even using ultrasound incorrectly can make matters worse. But by using it correctly, that risk is dramatically decreased.”

Augusta University Health was one of the first health systems in the nation to combine ultrasound training and required testing on a cadaver model, which required months of preparation, Lyon says.

“We even had to come up with a unique cadaver model,” he says. “Because traditionally, the veins in cadavers are flat, but we obviously need them open for this type of training.” The cadaver veins were filled with ultrasound gel.

This training is just one part of a larger effort to make patients safer, says interim Chief Medical Officer, Dr. Phillip Coule, ’96. “This continued training is an opportunity to continue to create and reinforce a culture of safety throughout the hospital.”