Georgia CORP is one of only a few programs in the United States that provides former obstetricians a path for re-entry into the profession.

“Delivering babies is hard, and delivering babies is time-consuming…

It’s a hard lifestyle to continue to deliver babies and give up chunks of your life in the hospital.”

That, in a nutshell, sums up why Georgia — and the entire country — is facing a shortage of obstetricians, particularly in rural areas. But it’s not the whole story. “It hasn’t always been a problem because people used to do obstetrics for their entire career,” says Dr. Chadburn Ray, associate professor and residency program director in the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology. “But this has been a problem in evolution for quite a while in obstetrics.”

It’s why Ray, also director of the Global Health Program in Obstetrics & Gynecology, lobbied for and helped develop the Georgia Center for Obstetrics Re-entry Program. Georgia CORP is one of only a very few programs that provides a path for doctors — in this case former obstetricians — to become recredentialed and fill the gap of practicing OB/GYNs in the state.

A challenging issue

Birth rates have been flat or on a decline for the past 20 years (although they rose by .1% in 2019). So that appears to beg the question: Why do we need all these obstetricians?

It’s simple economics: Although birth rates have remained unchanged, numbers of women — and actual births — have not. Population growth means that the demand for women’s health services continues to exceed the supply of OB/GYNs who are being trained. For example, only 200 new residency training positions were added over the last 25 years, even as the number of U.S. women over age 18 has increased by 33 million.

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, half of all U.S. counties don’t have even one OB/GYN. That’s more than 10 million women who either don’t receive the care they need or must drive hours to receive it —hardly a good solution during pregnancy.

Those statistics came out in 2017, and by this year, ACOG said there will be 8,000 fewer OB/GYNs, even as the demand for women’s health services grows by 9%, just in Georgia alone.

The Future of the OB/GYN Workforce, published by ACOG president Dr. John Jennings in 2014, also reported the pressing issue of retiring OB/GYNs: One-third are older than 55; nearly 40% are fast-tracking retirement plans; and by 2017, 18% were expected to reduce work hours, 10% to seek a non-clinical job and 9% to actually retire.

The other demographic challenge is that today, more than 80% of doctors training to become OB/GYNs are women. These are physicians who may one day become pregnant themselves, have children and want to take some time off to raise those children. Still others — both male and female — might need time off to care for a loved one who is sick or to deal with their own health issues.

“Whatever the reason, we slowly started seeing people get out of obstetrics, and most people never went back and never had an opportunity to go back because there was no mechanism for it,” says Ray.

The catalyst

Ray knew the foundational issues of physician re-entry. But then he picked up The Augusta Chronicle in 2013 and read a report on Georgia’s maternal mortality — defined as the death of a mother during pregnancy or the first year after giving birth. Not only did the state lead the nation that year, but the Augusta health district led the state.

“It was stunning to read something like that,” Ray says. “It was a shock moment.”

Two years earlier, the Georgia Obstetrical and Gynecological Society had predicted that within five to 10 years, more than three-quarters of Georgia would be without adequate services. By 2015, that was coming true as physicians began hitting retirement and their associated birthing centers began to close. Five closed in Georgia in just two years, with 34 closing over the past 20 years.

Then a letter came across Ray’s desk from Dr. Don Korkis, a former OB/GYN who left the field and was working as a pharmacist in Colorado. “He is one of the reasons why Georgia CORP exists,” says Ray, “because he wrote a letter to every residency program in the country asking whether or not there was some mechanism for him to be recredentialed.”

At the same time, Pat Cota, executive director of the Georgia OBGyn Society, called Ray to ask about a physician who had lived in Africa for several years delivering babies as part of mission work and needed to be recredentialed. “Is there a way you could help her?” Ray recalls Cota asking.

There wasn’t, then. But, says Ray, both those contacts “weighed on me tremendously.”

He brought those conversations to Dr. Michael Diamond, then-chair of the MCG Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, who agreed that Ray should put together a proposal. Ray started collaborating with the Georgia OBGyn Society, the Georgia Maternal and Infant Health Research Group, and GME programs in OB/GYN statewide, as well as with Augusta University’s government relations group.

As a result, Ray testified before a Georgia Senate subcommittee in Tifton, Georgia, and ultimately Georgia CORP was approved and funded. “To my knowledge, nowhere in the United States has a state-funded program like this. Many people may tell you, you can’t do it, and many people may tell you there are good reasons why you shouldn’t do it, but we did it anyway, and we’ve proved its feasibility.”

At the time, only eight physician re-entry programs existed in the United States, but none in the Southeast and none dedicated solely to OB/GYNs. Georgia CORP changed that.

OB/GYNs again

The 90-day program evaluates and assesses OB/GYNs interested in delivering babies again after a career hiatus and provides retraining using Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competency milestones, a flexible curriculum that includes simulation, and clinical care under the supervision of academic faculty at MCG. For the future of the program, Ray wants to move it into rural areas where doctors can retrain right where they may one day practice again.

For now, participants have self-referred, finding the program online. Once enrolled, participants must sign a contract stating that they will practice in Georgia. The program trains one participant at a time, with a maximum of four per year, which Ray says the program has reached.

There were challenges. The biggest hurdle was the cost of malpractice insurance. Although the state funding meant that Ray could offer the program for free, OB/GYNs were still responsible for purchasing the insurance, which can run $25,000 or more for just three months’ coverage.

Some early participants paid that amount, until legalities were worked out so that the program could be banded as a structured volunteer program and allow participants to be covered under the Georgia Department of Administrative Services.

As residency director, Ray also must put a priority on ensuring OB/GYN residents are still getting good OR experiences. That’s required a balancing act, to admit the right participants and enough to help make a difference, but not so many that too many hands are jostling for surgery time.

The program began in 2016, and the first to sign up was Dr. Janet Boone, who had left obstetrics but stayed in gynecology so she could care for her young children. “She went from not having delivered in 12 years to now she delivers 12 babies a day,” says Ray.

Boone is exactly the type of physician the state wants to train back — someone who not only loves OB but who wants to work in rural Georgia. After completing Georgia CORP, Boone moved from Gainesville to Austell, Georgia, where she is a laborist for the WellStar Health System but also travels to rural Georgia to cover labor shifts for rural doctors on vacation or on weekends.

Another was Dr. Ryann Cowart, a family medicine physician and former obstetrician who entered the program with a goal of going into academics to teach others how to deliver babies. “We helped her do that,” says Ray. “That downstream effect — it’s a wonderful piece of it.”

Korkis, whose letter weighed so heavily with Ray, was unable to be credentialed for surgery since he had been out of obstetrics for nearly 20 years. But with a mission to work in rural Georgia, he was accepted into the program, which allowed him to return to medicine. He now works in prenatal and women’s health in at-risk areas of the state.

It’s a start

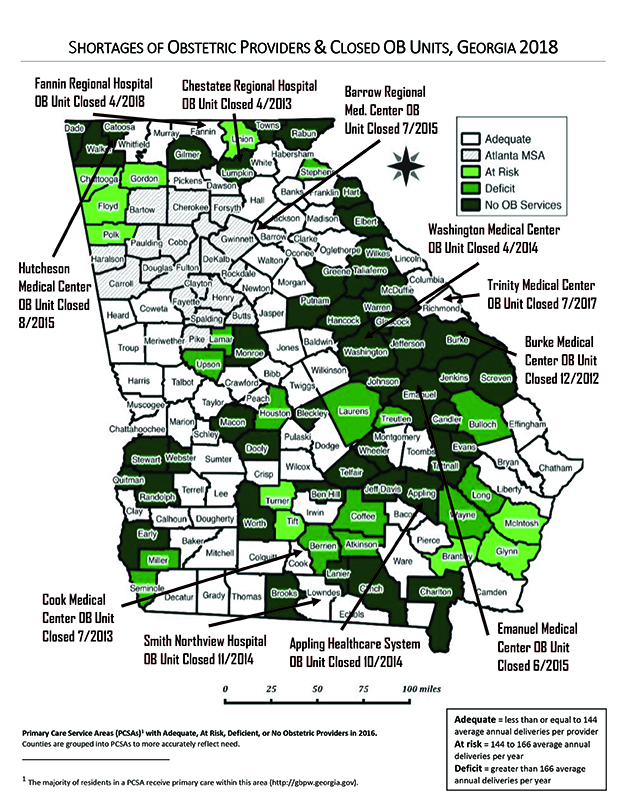

A 2018 map of the shortages of obstetrics providers and OB units in Georgia highlights counties in vivid shades of green, darker green and black where those providers are at risk, where there’s a deficit or there are no OB services. “It’s an important map, really, because when you look at it, there’s a desert all around us,” says Ray. “Patients have to go a long way each way for their doctor appointments.”

To date, Georgia CORP has returned seven doctors to delivering babies, and Dr. Emily Culbert is set to be the eighth.

“Do I think it’s made a difference in maternal mortality in Georgia yet? I have no idea,” says Ray. There are many reasons women die in childbirth — not just access, but also poorer health, racial bias and economics.

“But I know I’ve made a difference in the lives of the doctors I’ve put back into practice and hopefully in the lives of the women they’ve cared for since they got out of the program. I am sure of that.”

In Practice

The latest to join Georgia CORP is Dr. Emily Culbert, who graduated from the University of Washington School of Medicine, completed her residency at Tulane University School of Medicine in New Orleans, and has been living and practicing gynecology in Oregon. She left obstetrics when she got a divorce —“With two youngish kids, it was too hard to be on call,” she says, but “I really missed it. I liked being in the hospital and the joy of delivering and the excitement of it and being an important part of a patient’s life.”

Her children are now 10 and 12. So Culbert wondered: Could I get back to delivering babies? She began Googling, but her searches were coming up mostly empty. “I was trying all different keywords, then MCG’s program popped up,” she says.

Despite the hoops she’d have to go through — such as getting a Georgia medical license and being willing to work in Georgia (she already has leads on a couple of possible positions) —“I was really happy to find one that existed, that wasn’t astronomically expensive and that wasn’t for nine months,” she says.

That was a year ago, and during that time, Culbert made arrangements to obtain her Georgia license and hospital privileges. She set up a schedule where she could live in Augusta for two weeks, then return home to Oregon for two weeks to see her children and continue working at Salem Women’s Clinic.

All the travel, she admits, “might get a bit old,” but it’s worth it. “I cross the country every two weeks, and people ask me why. They say, ‘When physicians get older, they usually stop doing OB.’ I guess for me there’s a certain attraction — just being able to take care of women that way. I’m so grateful to the program and to Dr. Ray. I’m really lucky it exists.”