LOOKING BACK

ON HISTORY

The press release posted by the Athletic Department on June 6, 2010, started very succinctly:

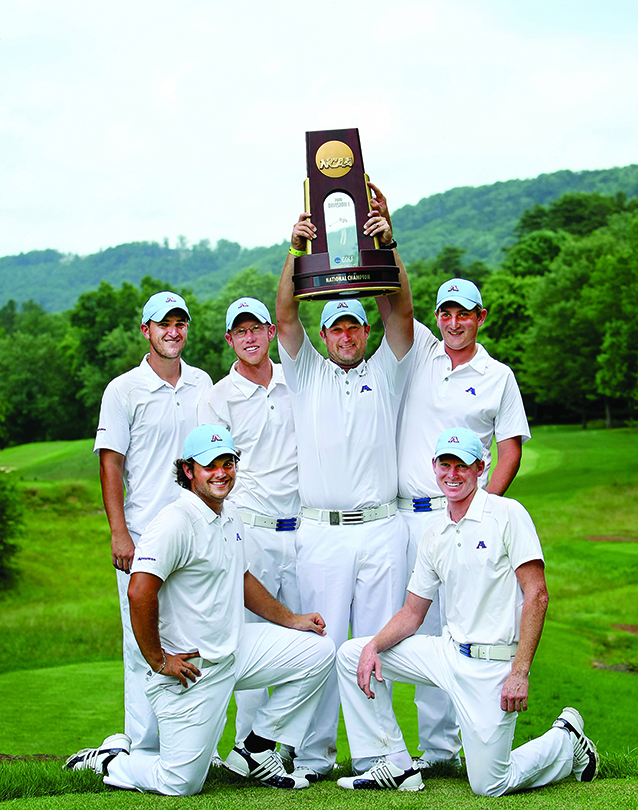

Augusta State Wins National Championship.

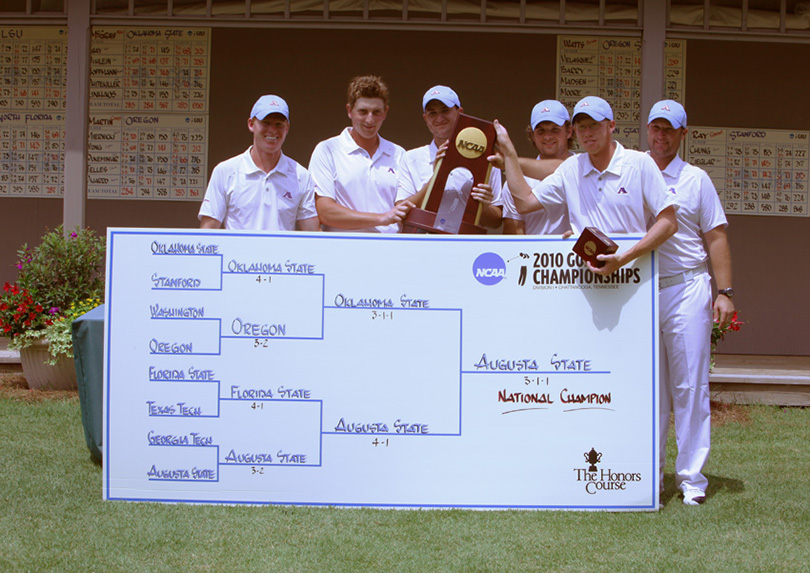

Augusta State captured the first National Championship in school history Sunday afternoon when the Jaguars took down Oklahoma State 3-1-1 in the championship match of the 112th NCAA Championships at The Honors Course just outside Chattanooga.

A year later, a similar press release:

Historic Day for ASU!

Augusta State won its second consecutive National Championship on Sunday afternoon when the Jaguars defeated Georgia 3-2 in the Match Play Finals of the NCAA Championship at Karsten Creek Golf Club.

Those are the improbable facts surrounding one of the most improbable feats in NCAA Division I sports, but behind the facts there’s a story to be told, and who better to tell it than those who lived through it?

the players

Perhaps no player’s road to Augusta was more unlikely than that of Mitch Krywulycz, a multi-sport athlete from Australia who came to golf at around 13, after doing everything from swimming to playing cricket to playing three different kinds of rugby.

With golf, everything just fell into place.

“I kind of fell in love with the fact that I was always involved in it and didn’t have to wait on teammates or wait for my turn,” he says. “That’s probably what appealed to me the most — I was just always involved.”

Because playing college golf in the United States allowed him to get an education while pursuing an amateur sport (in Australia, he’d have to choose one or the other), he committed to Georgia Southern University and only ended up in Augusta because he stopped by on the way down to Statesboro.

“I sat in [head men’s golf coach Josh Gregory’s] office for about 20 minutes,” he says. “I told him, ‘You have a nice range here and I trust you, so I’ll just come here instead.’ Being from Australia, I thought it was like high school — you just pick somewhere and you go, so what does it matter?”

Carter Newman couldn’t have been more different. Raised in Augusta with a father, Dean Newman, who played golf for the Jaguars in the late 1970s, Newman took up golf at an early age. A solid player who nevertheless wasn’t highly recruited out of high school, he too found himself sitting in Gregory’s office.

“It was a no-brainer for me,” he says. “The team had had some success years prior, and I was excited to play DI golf. I couldn’t think of a better place to do it than here in Augusta.”

Growing up in Macon, Georgia, Taylor Floyd went to a small private school, so when he visited Augusta with his parents, the size of the city and the campus was a little intimidating. But after sitting down with Gregory, coming to Augusta just felt like the right decision.

“I pretty much committed a week or so after coming,” he says. “I was very, very impressed with the facility that they had for the golf team, and Josh especially was just a really cool dude. I knew it was going to be a good fit for me personally.”

Of course, the team really changed with the transfer of Patrick Reed, who signed with the Jaguars in April 2009 after playing in three of four events during the Fall 2008 season for the Georgia Bulldogs. When he joined the Jaguars, he was ranked No. 40 in the world amateur rankings.

“When Patrick came in, the whole dynamic just sort of changed,” Newman says. “We went from a preseason ranking barely in the Top 50 to a preseason ranking in the Top 10.”

Adding a dominant player like Reed to a team that already had a dominant player in Henrik Norlander shifted things. In Norlander — a Swede who came to Augusta and immediately made his mark with one of the best freshman seasons of any Jaguar men’s golfer in the history of the program — they’d had a player who could reliably win. With Reed, they now had two, which makes all the difference when it comes to the match play portion of the sport.

“You can’t win five matches without winning three,” Newman says, referring to the head-to-head competitions that decide things at the National Championship.

As improbable as it might have been, the 2009-10 Jaguars had the makings of a true contender.

the coach

For the players, coach Josh Gregory was the real deal — not just a smooth talker who could convince people to attend Augusta State, a DII school with a DI golf program, but someone who could get the most out of them — as individuals and as a team.

Not the type of coach to enforce strict workouts and impose a lot of structure, Gregory trusted the players to do the things they needed to do in the ways that worked best for them.

“He believed in identifying talent, building a relationship and giving players all the resources they needed to go out and improve,” Newman says. “He wanted guys who really wanted it. He didn’t want to have to walk them through the whole thing — he wanted a team that would go out and put in the work themselves.”

It was an approach that worked for this particular group of highly competitive players. He spent more time working with Reed and Norlander, and the others understood. They went along and did their own thing their own way.

“He put the responsibility on us to go out and get better,” Floyd says. “And we did.”

small school, long odds

No one knows better how unlikely the Jaguars’ consecutive national championships are than longtime athletic director Clint Bryant.

Because of a now-discontinued policy called multi-classification, Augusta was able to field a DI golf team without having to hit the money and scholarship thresholds of competing as a DI school in all sports.

While the decision to compete that way made sense — the men’s golf team had been successful in the Big South and had its own course, the impressive Forest Hills Golf Course — there was a trade-off: Augusta would continually compete against schools with more resources, more money and therefore more natural, built-in momentum toward performing well than the Jaguars could ever dream of.

In spite of all that, however, little Augusta State had something bigger than money going for it: Augusta itself.

“Augusta is used to golf being played at the highest level,” Bryant says. “Over in Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain, Australia, South Africa, they don’t call it the National, they call it Augusta, so when a kid in one of those countries says they’re coming to Augusta, Georgia, to play golf, it’s like a kid in our country saying they’re going to play basketball at Duke or UCLA. It’s a really big deal, and we’ve been fortunate to have an international flavor of golfers that have put their footprint here.”

Another advantage, obviously, is having Forest Hills, the No.1-ranked public course in the state, as the team’s home.

For the players, however, the struggles of being a small school playing with the big boys came down to more than just a good David and Goliath story — they could feel the difference in the most practical ways, including their team vehicle.

“My freshman year we were driving around in an Excursion,” Floyd says. “We’re taking five dudes plus our coach to tournaments all over the Southeast riding around in a Ford Excursion.”

In fact, they had a running joke about knowing how to pack it, which wasn’t easy when everybody’s got a golf bag plus a clothes bag. That’s 10 bags trying to fit in an SUV that already has six people in it.

“Other teams would pull up to golf tournaments in their brand new $100,000 Mercedes vans with Wi-Fi and DirecTV attached to the roof, and we were pulling up in a 2008 Ford Excursion, and we were beating everybody,” Floyd says. “It was just crazy to us that we’re out here doing this and there were teams that had all these plush things that we didn’t even really know existed.”

the competitive spirit

When you’re as competitive as this group of players, overcoming obstacles comes with the territory, and college golf is built around overcoming obstacles.

“The thing about college golf is, you go out there every day and play our own ball — you get your own score — but it just so happens that you add that up with four other guys for a team total,” Floyd says. “So you’re playing individually but for the betterment of the team.”

And for this particular group of guys, the environment and the personalities meshed to get the most out of that scenario. Strong individuals built into an even stronger team.

“We were just a super competitive team,” Krywulycz says. “We lived and died every day by beating each other.”

As with all competitive groups, that sometimes produced some tension.

“There were a lot of arguments and disagreements throughout the year, but normally it was always related to us just being a super competitive group of people that just wanted to beat each other, and everyone just wanted to get better,” Krywulycz says.

That environment, according to Krywulycz, created a team that had a grinder mentality — a group that, particularly with Krywulycz and Floyd and Newman, was willing to grind it out and wear down other players, if not with raw talent, then with grit and determination.

For Newman, that makeup provided the perfect structure for success.

“In my opinion, in college golf you’ve got to have two guys who can go out and potentially win the golf tournament every week, and that’s what we had in Henrik and Patrick,” he says. “We were so confident in their ability to go out and play a good round that I think it freed the rest of us up a bit. So we did what good three, four and five players on a DI college golf team should do: we shot around even par, and when you added it all up, we had a really solid team.”

According to Krywulycz, it all comes back to being competitive.

“Adding Henrik and Patrick and the ability that they had to shoot the rounds they did allowed us to compete at a national championship,” he says. “And then, I think, right at the end of the final matches that year, it probably fell back to that competitive nature we had. We were just a really aggressive, competitive team — more so than probably anyone else.”

Nationals

Getting to Nationals is the culmination of a successful season, but once there, the season starts anew: Over the course of a week, 32 teams start, and only eight make it to match play. So for the first two rounds you’re just trying to claw your way to the top eight so you can advance. Which is tough in itself, but even tougher when you add in the practicalities.

“Every morning, we packed our bags just in case we got knocked off,” Krywulycz says. “But I remember thinking the whole week, ‘We’re going to be here for the whole week. We’ll keep playing. We only have to win three out of five matches. We’ll be here the whole week.’”

But it wasn’t easy. They had to play a good final round to make it to match play — to get to the point where they could go head-to-head with the top teams in the nation: Georgia Tech in the first round. Florida State in the second round. Oklahoma State in the third round.

“We just embraced the underdog mentality,” Newman says. “Who’s going to expect Augusta State to compete with Georgia Tech, Florida State and Oklahoma State?”

Expected or not, that’s just what they did.

“It was an unbelievable team effort,” Newman says. “We all just played our roles throughout the week and stepped up at the right times.”

Newman had a bad second round in stroke play but went out strong in the first match play round, shooting four under on the front nine.

“I’m sure my teammates didn’t expect me to win,” he says. “I was playing a kid that totally killed me in stroke play.”

Newman did what he had to do when he had to do it, as did the others, which brought them to the final round of match play and a whole new set of obstacles.

the final round

For Floyd, the final round looked like it was going to be a disaster before it even started.

“To this day, I don’t know if it was food poisoning or something more than that, but it was brutal,” he says.

He started to feel a little rough after the match against Georgia Tech. At dinner that night, he couldn’t really eat, but it wasn’t until he got back to the hotel that everything really went south.

While the rumor that he received an IV makes for a dramatic story, the truth is he downed as many Gatorades as he could that next morning and, thanks to the Oklahoma State coach agreeing to let his match go off last to give him extra time to warm up — he’d been in a fetal position in the back of the van while the others were out at the range and getting their matches started — he was able to stabilize physically so he could put himself together mentally.

“There’s that old saying: Beware of the sick or wounded athlete,” he says. “Once I actually got up and moving and realized the severity of the situation, it all kind of blacked out, and the adrenaline took over.”

Norlander and Reed did what everyone expected Norlander and Reed to do — they won their matches — which left it up to Newman, Krywulycz and Floyd.

Newman lost the first match, but it takes three to win five, and Krywulycz and Floyd were still on the course, Floyd pulling up the final pair.

“Don’t get me wrong — walking around a golf course lugging a 50-pound bag when you’ve got food poisoning or the flu or whatever it was isn’t much fun, but you’re out there in the final round of the national championship,” Floyd says. “You’ve got to just suck it up and do it.”

Living up to his grinder reputation, Krywulycz was hanging tough and scrapping, relying on his toughness when things started to turn against him.

“That last match in the final was probably the epitome of how I played all year — and in general how I play golf,” he says. “I just tried to stay in it long enough.”

Four down through five holes, a fan came up and told him to hang in there, and he thought, “I’m doing everything I can, and it’s not going to be enough.”

But that’s the thing about being a grinder. Sometimes, hanging in there gets you where you need to be, and on 18, he evened his match. And when he did, he smiled. It was as if he could feel the tide turn.

“Ever since I got to college and figured out what college golf is all about, I’d always dreamed of being in that spot and playing for a national championship,” he says. “It was an exciting moment that probably comes back to how our team fought every day against each other to get better — it probably allowed me to think that way. I think if I was on another team that wasn’t as competitive, I wouldn’t have had the experience to just be in the moment and think, ‘How good is this?’ It probably allowed me to finish out the match.”

With Floyd still battling it out behind him, Krywulycz forced a playoff. Both he and Oklahoma State’s Kevin Tway managed to hit the fairway with their tee shots, and their approaches both landed within 20 feet of the hole on the 405-yard par 4. Shooting first, Krywulycz left his birdie putt just short. Tway conceded the par putt, then hit his own birdie putt nearly 5 feet past the hole.

On 17, Floyd could see through the trees toward the action on No. 1.

“Josh was with my group, and we realized the big group of people over there had kind of hushed, so we knew somebody was about to putt, and it just so happened when I looked over there, it was Kevin Tway lining up about a 5- or 6- footer to extend the match,” Floyd says.

It was one of those magic moments. Without saying anything, everyone on 17 stopped and watched what was happening through the trees.

On No. 1, Krywulycz was watching, too, but mentally he was already thinking about the next hole.

“You’re always taught in match play to protect against the worst outcome, so I was thinking, ‘What would happen if he makes his putt and extends the playoff,’” he says.

He’d lost the second hole to Tway earlier in the day, so Krywulycz was thinking about his tee shot.

What does it look like? What does it look like?

“That’s what I remember repeating to myself,” he says. “‘Picture your tee shot. What does it look like?’”

As competitive as the Jags were, they didn’t like too many teams, and not too many teams liked them. But Tway — Krywulycz had a lot of respect for him, so when Tway’s putt, the most important putt of his collegiate career, slid by the hole, giving Krywulycz the match and the Jaguars the championship, Krywulycz’s first inclination was to feel bad for him.

“I remember thinking of how bad I wanted it, and then how obviously he wanted the same thing and how bad he was probably going to feel,” he says. “So we didn’t initially celebrate. We probably waited 10 or 15 seconds for him to pick up his ball and shake hands and walk off the green.”

On 17, that silence was deafening.

“I remember seeing that putt miss and not really hearing anything but that awkward silence for a couple of seconds,” Floyd says. “Then our fans and our guys started to celebrate. I remember dropping my putter and going to Josh and giving him a big hug.”

The next few minutes were kind of a blur.

“You’ve pictured winning, but not really what it looks like after,” Krywulycz says. “It’s just kind of a unique moment, and as time went on it started to get better and better. You let it sink in a little, and then on the drive back from Tennessee as the day turned into night, it just got better as it really sank in.”

It was, he says, a lot to process.

“You know you’ve won, but you don’t know what that means,” he says. “You think you do, but you don’t.”

what it means

After they sealed the championship, their close-knit little world got a lot bigger. There was a police escort to Christenberry Fieldhouse, where several hundred people waited to welcome them home. Then there was a trip to the White House — the White House; a reception at the Augusta National; a banquet back at Christenberry, where they received rings for their championship.

It was a special time for all of them.

“We were a pretty close-knit team, and all that all just brought us closer,” Newman says. “We’d always talked about what it would be like to win a national championship, and you spend your entire college career working hard with these guys, day in and day out, to try to achieve something, and when you can get to the end of the line and say you did it …”

They did it, all right.

And then they did it again.

Back-to-back national championships are rare in DI golf. Since 1980, only one team did it before Augusta, and only one team has done it since.

“The first one was like a fairy tale,” Krywulycz says. “The second one was kind of just to show everyone we could do it.”

Not only did the Jaguars win the next year, they took down No. 2 seed Georgia Tech, top-ranked tournament host Oklahoma State and then No. 5 seed University of Georgia.

“When you go out and you prove that you can do it, you’re not necessarily the underdog anymore,” Newman says. “I really think for us, the confidence just went to a completely different level.”

Even with a target on their back, they knew the odds were against them.

“We knew the odds we were up against,” Krywulycz says. “We knew how good the other teams were, and we knew their advantages going to Oklahoma. It didn’t make sense for us to win.”

But they did. The DI golf team at the DII school won consecutive national championships.

Band of brothers

“It’s crazy for me to think that it’s been 10 years,” says Newman, who played professional golf for about a year and is now working for Augusta Sportswear. “There’s not a week that goes by that it doesn’t get mentioned to me in some capacity.”

For Floyd, who played professionally for three years and is now in the insurance business in Augusta, the memories remain powerful.

“Every Friday we went to dinner; every Saturday we hung out. On the weekends we went out and did things together,” he says. “We essentially became best friends, so that makes it even more cool.”

As the head coach of the College of Charleston, college golf has remained a major part of Krywulycz’s life.

“It’s all I do every day,” he says. “It’s all I think about, and that’s directly related to the experience I had in Augusta.”

As of March, Norlander has played 66 PGA events and has won almost $1.8 million. Reed has eight PGA Tour victories, has earned over $30 million and returns to Augusta every April to play the Masters, which he won in 2018.

When it comes to the overall legacy of the championship seasons, Bryant probably says it best.

“We continue to try to make not only this university very proud, but to make the people in this community very proud of what we have done and what we’ve accomplished,” he says. “Because one of the things we say to all of our athletes is, ‘No matter where we go or where we compete, there is one constant on all our uniforms, and that’s Augusta.’ That’s a powerful brand and a powerful message for us all.”

© Copyright Augusta University. All Rights Reserved.

For nearly 200 years, Augusta University and its legacy institutions have been centers of learning and drivers of discovery and innovation in Augusta, the state of Georgia and beyond. Our community of alumni, students, faculty and friends are amazing people living incredible lives and making invaluable contributions to our world.

We are pleased to publish four magazines in which we get to tell their stories: