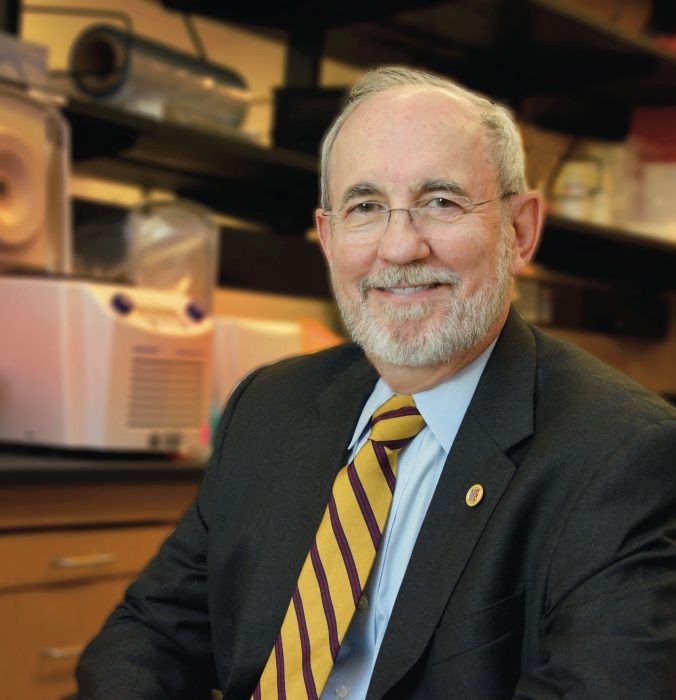

Whether he’s talking about his day job at his biotech company or his other day job scouring oceans and jungles across the world for downed warplanes, the common thread is clear.

“It’s all about the impact those two things can have on people,” says Dr. Pat Scannon (’76). “That’s what matters to me.”

Scannon, a Kentucky native who landed in Augusta as a military brat, admits he’s always been obsessed with chemistry — getting his first set in third grade because he liked “to burn things and make colored smoke.” It stayed with him. After college, he enrolled at the University of California at Berkeley to earn his doctorate in organic chemistry. While there, he says he began to find himself intrigued with something new — the chemistry of medicine, or how chemistry helps bring about new treatments and cures.

“I can still show you the spot on the UC Berkeley campus where I went from wanting to be a chemist to wanting to be a physician,” Scannon says.

He came back home to Augusta in 1972 and enrolled at the Medical College of Georgia. After graduation, he headed back to the West Coast to fulfill his commitment from the U.S. Army scholarship that had put him through medical school. He completed an internal medicine residency at Letterman Army Medical Center in San Francisco, and because he already had a doctorate in chemistry, the Army asked him to stay on and do research at Letterman’s Army Institute of Research. He still owed them a few years.

“I was doing research looking into the development of hemoglobin-based blood substitutes,” he says. “That was really my first foray into biochemical research, and it was really interesting to me. I began to become aware of the subtleties, of the things you can do with proteins and synthetic molecules.”

While researching blood cells and manufactured blood products, Scannon began to take note of monoclonal antibodies, laboratory-produced molecules engineered to bind to cells or proteins that had only then been recently discovered. The antibodies have many applications, such as turning the body’s immune response up or down. At the same time, Scannon says, he noticed a major shift going on in the technology world – from what had been an IT-based business (think Silicon Valley) to more interest in biotechnology.

He isn’t sure how, but in 1980, the idea came to him to start a company that could develop monoclonal antibodies as therapeutics. The idea for XOMA was born. Working to develop potential new therapies was a natural progression, he says.

“I had just finished my residency, and there were certain parts of medicine that I had a real tough time with. One of those was oncology,” Scannon says. “The only thing medicine had to offer were highly toxic chemotherapies and radiation therapies, which are incredibly tough on patients.”

He saw in monoclonal antibodies the opportunity for new, gentler treatments — the hope being that those manufactured antibodies could bind specifically to diseased cells in humans, like cancer cells, and make them more visible to the immune system, with minimal side effects.

Scannon started knocking on the doors of venture capitalists in 1980. “It was like the Wild West out there then,” he says. “No one knew what they were doing. The most business experience I had at the time was selling doughnuts as a Boy Scout on Walton Way. In the process of starting a company with a totally new concept, I was shown out of a lot of buildings back then.”

But then, Genentech Inc., a little-known genetic engineering company, went public. Their stock skyrocketed overnight — even with no marketed products or profit to show for it. Scannon calls that the biggest boost he ever got. Suddenly, biotech was a new buzzword, and raising money wasn’t so hard. XOMA opened its doors in 1981.

Today, the company remains at the forefront of research into monoclonal antibodies. A few years ago, scientists there developed a special class called allosteric modulators, which instead of acting like a light switch to turn immune response on or off, act more like a dimmer switch. “You can literally design how much you want a receptor to respond,” Scannon says excitedly. “There are many diseases where you neither want to turn a cell completely on or off.”

These dimmers have potential as new therapies for endocrinologic diseases such as diabetes, parathyroid hormone and adrenal gland diseases. Two of their antibodies will be in phase two studies this year. XOMA has also been fortunate to work with pharmaceutical companies — doing research collaborations with the likes of Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson, he says.

For nearly four decades, the focus has remained consistent.

“It isn’t enough for me to do medical research unless I can find a path for doing some good and taking care of patients,” he says. “The Medical College of Georgia developed in me a real love of taking care of patients, and I’ve never lost that intense feeling of wanting to try to help.”

A different kind of research

Even as he was busy building XOMA from the ground up, Scannon found himself looking for a new hobby in the mid-80s. That search led him to scuba diving and to what would eventually become a second full-time job.

Searching for a spectacular underwater view, he signed up for a group diving trip to Palau, a group of islands in the Pacific Ocean known as one of the world’s premium scuba diving destinations. It was also the location of several battles with Japanese forces on land and in the air during World War II.

He and his wife stayed a few extra days in Palau to take in more diving. “In a moment of insanity, we hired a guy and just said, ‘Take us to a place where we can dive and see wreckage,’” he says. “We got to know him over the next couple of days, and he told us about this obscure place, back behind a little island, that no one had really investigated.”

Just as they rounded the corner of the island, they saw it: a wing sticking out of the water. Scannon jumped out of the boat to investigate.

“In addition to being a junior chemist as a kid, I had built just about every model airplane you could find, so I had some sense that this might be an American wing,” Scannon recalls excitedly. “I saw part of the engine, and it said ‘…eneral Electric.’ I knew it probably wasn’t a Japanese plane, but no one knew much about it. I decided I was going to find out. ”

In early 1944, during World War II, America was making progress toward the takeover of Japan’s Pacific frontier territories. The islands of the Pacific, like Palau, were important because they protected Japan’s territory in the Philippines, Indochina, Malaya, Borneo and the Dutch East Indies. The islands were the scene of many air fights between the U.S. and Japan, and many American and Japanese planes still lie beneath the ocean’s surface and in the jungles of Palau — many with their crews’ remains still in them.

Scannon was determined to change that.

“I started going back by myself and looking for wreckage, and I think maybe the second or third time I went, I was deep in a mangrove swamp and I got in trouble,” he says. “I just barely got out of it. I decided then that I would find some other knuckleheads to do this with me.”

That was the birth of the Bent-Prop Project. Now, once a year, a group of volunteers travels with Scannon to Palau to find planes in the Pacific and in the mud and muck of the surrounding jungles. The group works with the Department of Defense’s POW/MIA Accounting Agency, which identifies the remains and notifies families when appropriate.

They found the first crash site underwater in 2004, with the remains of its eight-man crew on board. The feeling of finding that lost plane was unexplainable, he says. But the most exciting part was the closure it brought to the families of those missing in action.

“It provided answers they never knew,” Scannon says. “There is something distinctly different in Killed in Action, which means remains were discovered, and Missing in Action. It’s hard to believe, but many families that I’ve interviewed, they are 99.9999 percent certain that the person died, but that left that .0001 percent.”

Until recently, BentProp had been limited, in the water at least, by the amount of air they could carry in the tanks on their backs. A tank of air typically gives you 10 minutes at 100 feet below – not much time for searching.

In 2013, the group joined forces with the underwater robotics teams from Scripps Institute of Oceanography and the University of Delaware, which completely revolutionized what they could do, allowing them to search larger areas quicker and more comprehensively, Scannon says. “It was completely state-of-the-art technology built using the same scientific principles that have been used to search for the Malaysia Airlines crash.”

In 2014, they found two crash sites. Last year, another. With the Scripps and University of Delaware teams on board, they had found more in two years than the past 14.

And they do all of this trying their best to stay under the radar – never telling a family they’re looking for a missing American. That worked until 60 Minutes and Anderson Cooper showed up. The resulting documentary aired to an audience of 17.5 million in November 2014 and was rebroadcast that following Memorial Day. Suddenly, they weren’t below the radar anymore.

“Families began coming to us,” Scannon says. “Hundreds of them.”

One of those families was Paul P. Bensman’s, a 25-year-old airman from Alton, Illinois, whose plane had gone down in the jungles of Palau.

In 2006, the group had found a crash site in the jungle that they knew had a three-man crew – one of them being Bensman. They held their usual flag ceremony and, per protocol, notified the Department of Defense about their find. The DOD team investigated the site, but were unable to locate remains. Scannon guesses that one possibility is that they were buried somewhere else, maybe by the Japanese. Since there was nothing to report, DOD put it on the shelf and Scannon’s group moved on to other searches.

The Bensman family had been among the millions who saw the 60 Minutes piece. They reached out to Scannon to see if, by chance, he knew anything about Paul’s crash. They knew through their own research that his plane had gone down in the jungles of Palau. Through that phone call, they learned so much more. Scannon also told the family about the flag ceremony they had held at the crash site to honor the missing soldiers – something they do every time they find a crash site.

Plans were made to bring the flag back to his family in a “small” get-together in his hometown’s Catholic high school. “When we got there, there were over 100 chairs,” Scannon recalls. “It wasn’t just his family, who had traveled from five states, but the entire community who were eager to be involved in something giving them some sense of what had happened to one of their own.”

The mayor declared it Paul P. Bensman Day. The local Veterans of Foreign Wars did a 21-gun salute. The local television station showed up. The group presented the flag from the original ceremony to one of Bensman’s sisters. Bensman had also been engaged when he died, and his fiancé had never come to grips with her loss, although she did marry eventually. Her daughter had seen the 60 Minutes piece, and the two were also in attendance that day.

“Before Paul died, he had sent her a record with a recording of his voice. She decided to play it that day,” Scannon says with tears in his eyes, the lump in his throat obvious. “She hadn’t heard his voice in 70 years, and here he was singing ‘You Are My Sunshine.’ There wasn’t a dry eye in the house.”

Examples like those are what keep him going. “The adventure part is very cool, but this is our way of saying thank you,” he says. “This comes back to the human part of my life. I was never really interested in the planes — I was always interested in the people.”