The emerging standard of care for big clots in big blood vessels in the brain

He wasn’t driving to work. He wasn’t alone upstairs in their rambling home doing his usual morning stint on the computer. He wasn’t across the country alone either as a locum tenens neurologist in North Dakota, where an aging population of less than 1 million is scattered across more than 71,000 square miles.

Instead, Dr. Edward Mendoza had coaxed his wife Kay down the spiral staircase of their Martinez, Georgia, home the morning of Wednesday, July 26. He wanted to surprise her with a built-in, lighted cabinet he had made to display some of their travel memorabilia and to go over additional construction work on tap for the day that she would have to oversee while he was at work.

Mendoza wondered aloud if the built-in was crooked then he kind of wandered off and became uncharacteristically quiet. Kay figured he was upset about the ongoing troubles with extensive renovations to their home.

Then he began staggering, his head cocked to one side. The comparatively small woman grabbed her six-foot husband around the waist and helped him sit down. Certain now that frustration was not the problem, she called 911.

The 71-year-old neurologist and retired lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Army was having a massive ischemic stroke.

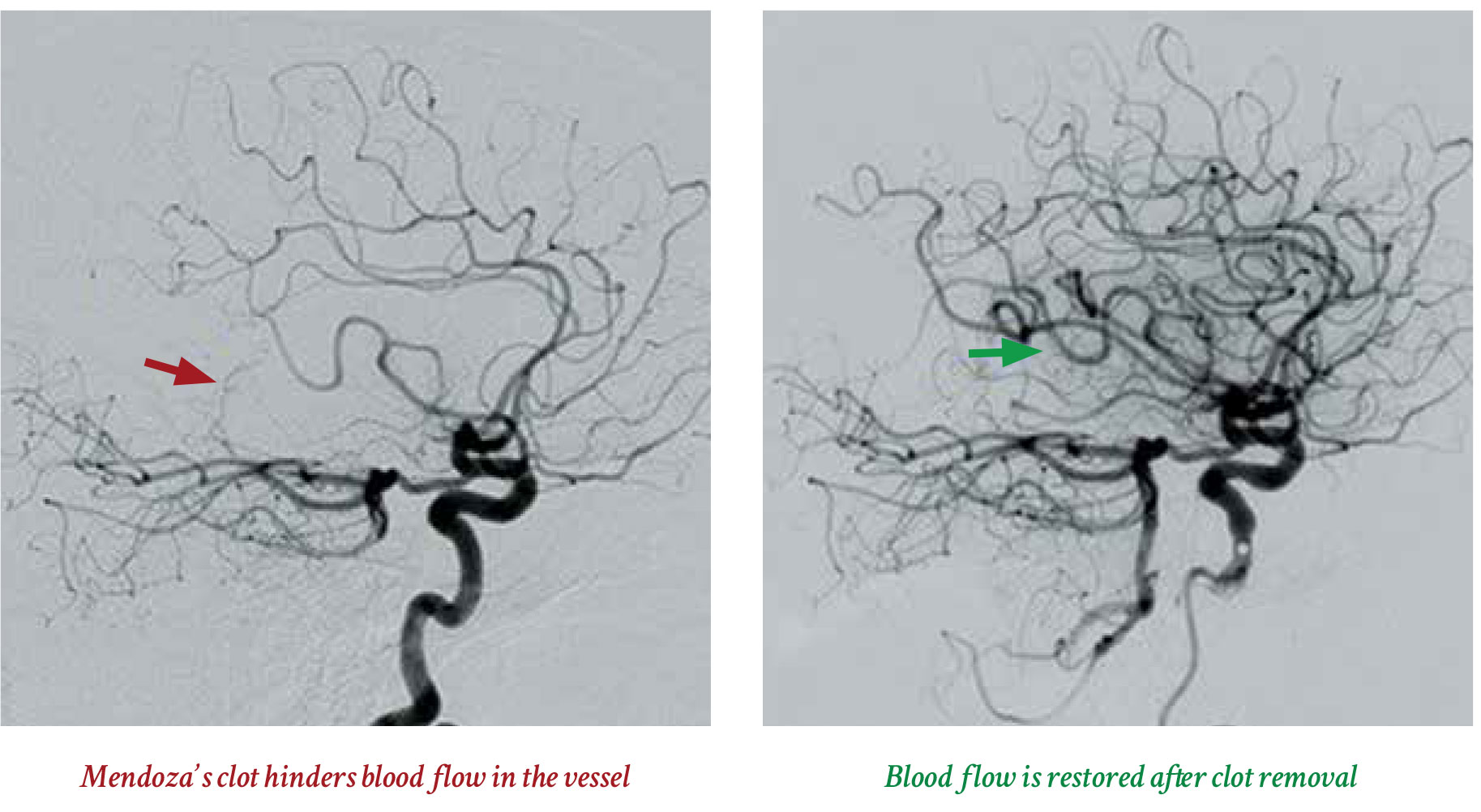

His clot was in the stem of the middle cerebral artery, the largest branch of the internal carotid artery and a common stroke spot. It feeds big areas of the brain important to motor and sensory skills as well as speech and language.

“The effects when that part of the brain has interrupted blood flow are not subtle,” says Dr. Jeffrey A. Switzer, director of the Advanced Comprehensive Stroke Center at the Medical College of Georgia and Augusta University Health. “They are very dramatic.”

Holly Hula, stroke program manager, saw Mendoza when he arrived, his long frame on a stretcher, his eyes deviated toward his left side, where the stroke occurred, the right side of his body paralyzed as a result. He could not talk, could not follow commands. She knew he was a neurologist and that meant he probably knew what had happened and what could result.

Time means brain

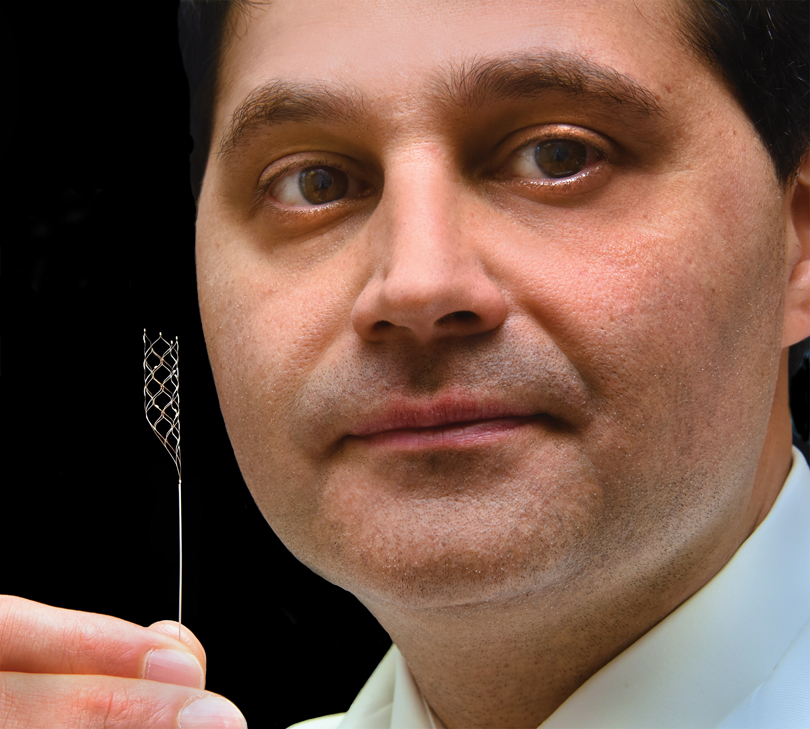

At 10:19 a.m., about an hour after his arrival, interventional neurologist Dr. Samuel Tsappidi punctured Mendoza’s femoral artery. He threaded a titanium-based wire up through the clot, placed a catheter over that, then injected dye to ensure he really had made it through the clot. He then pushed the self-expanding clot retriever, which looks a bit like a piece of chain link fence, through the catheter and the clot. There is a soft pop as it expands. Tsappidi pulled Mendoza’s clot out in two pieces, but at one time, the most desired result. The neurology resident closed the groin area at 11:14 a.m.

Forty-eight hours later, Mendoza walked out of neuro intensive care.

Big clots in big vessels that affect big portions of the brain occur in about 20 percent of acute ischemic strokes and mechanical thrombectomy, while still not widely available in the United States, is considered today’s standard of care, Switzer says.

It’s also a point of enthusiasm and pride among MCG stroke team members.

Like his patients, endovascular neurosurgeon and 2002 MCG graduate Dr. Scott Y. Rahimi likes the essentially instant results, as those vital vascular trees fill back in and brain tissue awakens.

Conversely in this severe stroke scenario, 80-90 percent of patients can be left moderately to severely disabled, if they survive, and even with tPA, the now 20-year-old clot dissolver also used to treat ischemic strokes.

With mechanical thrombectomy, 40-50 percent of these patients can regain their independence if not quite 100 percent of their function, Switzer says.

Stroke, like trauma, appears to be a bit of an equalizer in that it can really happen to anyone. The MCG team has treated patients in their 20s and in their 80s. There are the usual risks like smoking, high blood pressure and cholesterol and obesity. But there also are risks like severe dehydration or a hole between the chambers of the heart from birth or atrial fibrillation, when the heart’s upper chambers sometimes beat randomly and out of sync with the pumping chambers below.

Mendoza was diagnosed with atrial fibrillation while a student at Emory University School of Medicine right after his heart rate soared while playing basketball. He always knew the risks but was too busy to dwell.

The American Heart Association says atrial fibrillation accounts for 15-20 percent of strokes. The MCG stroke team and Mendoza agree that it accounted for his. Inefficient beating can cause blood to pool in the heart, clotting factors can pool as well and clots can form, like the fresh red one Tsappidi pulled out of Mendoza. Clots that break off from diseased arteries are more yellowish, like cholesterol, often their primary component.

Risks and rewards

Unlike more established trauma systems across the nation, there are still problems with patients getting to a hospital and to one that can remove those clots even in the heart of the stroke belt.

Denial and delay are definitely two problems faced by EMS personnel, says Jody Stafford (see MCG Medicine, Spring/Summer 2015), a paramedic for Augusta-based Gold Cross EMS, who was attending a recent stroke assessment course taught by Hula to help address these issues. “Everybody is in denial, nobody wants to admit they are having a stroke so that puts us behind the eight ball,” he says.

“This is one of those things we really can’t do anything about until we get them to the hospital,” Stafford adds. “It’s real imperative that we get them there as quick as we can.” Like with cardiac arrest, an ischemic stroke makes Stafford think about time and lost tissue.

Our brain is pretty much us

When he was in medical school at MCG, Rahimi thought for a time about specializing in vascular surgery because he liked the fine motor work of dealing with blood vessels. In anatomy, he can remember dissecting out all the blood vessels, even when he didn’t have to.

When it was time for his neurology rotation, which at the time was combined with neurosurgery, his friends told him that he could get a better grade in neurosurgery. He believed them, swapped out his neurology spot and ended up in the operating room watching neurosurgeon Dr. James Fick operate on a gliobastoma, a super-aggressive brain tumor. When Rahimi saw the pulsing brain, the blood vessels on its surface, he found a calling and went to then-neurosurgery chair, Dr. Mark Lee, that day.

“This is probably as instantaneous as it gets,” Rahimi says, looking at an angiogram of the vascular network in the brain that is restored, much like a tree revived by the spring, following mechanical thrombectomy.

He was at Emory completing his neurovascular surgery fellowship, where the Mechanical Embolus Removal in Cerebral Ischemia, or MERCI, device, the first Food and Drug Administration-approved retriever to remove clots in an ischemic stroke, was already in use. MERCI had a balloon catheter to block blood flow during the retrieval process and a coil that straightened out after it passed through the catheter and clot, recoiling on the other side to better grasp the clot. The second generation of this device worked better than the first but overall success was not great, Rahimi says. The Penumbra Aspiration System followed a few years later, which basically suctions the clot out. Stent retrievers, like the ones used at MCG and its health system, would come next.

While clinical trials of all the devices reflected benefit in each, side-by-side studies ultimately showed the stent retrievers had better functional outcomes in patients.

The third time can be the charm

The FDA first approved the stent retrieval device in patients who did not get or did not respond to the clot buster tPA in 2012, and four years later declared it an initial therapy for ischemic stroke. The FDA cited studies that showed 29 percent of patients treated with the stent retrieval device as well as tPA and other medical management like blood pressure control, had few to no residual symptoms following an ischemic stroke like Mendoza’s. That’s compared to

19 percent in patients who did not have mechanical thrombectomy.

Just this February the FDA extended use of the Trevo clot retriever up to 24 hours after the onset of stroke symptoms following results of the DAWN trial, which showed 48 percent of patients treated with the device were functionally independent versus 13 percent who received medical management only.

Used well, tPA could dissolve a big clot like Mendoza’s maybe 30 percent of the time, Switzer says. But when his interventional colleagues Rahimi and Tsappidi go after a clot, there is more like an 80-90 percent chance they can remove the clot and more rapidly reestablish the flow of blood and oxygen.

As with Mendoza, they often use tPA as well to start to eat away at the big clot and maybe even give them more room to work inside the blood vessel. tPA can be particularly beneficial when patients are in for a long transport to the stroke center, like the rural communities MCG serves with its telestroke system, REACH, Switzer notes. “That can mean two more hours of dying brain cells.”

“Time is critical following the onset of stroke symptoms,” commented Dr. Carlos Peña, director of the FDA Division of Neurological and Physical Medicine Devices in February. “Expanding the treatment window from 6 to 24 hours will significantly increase the number of stroke patients who may benefit from treatment.”

But time matters even more for some of us. “They say you lose almost two million brain cells a minute without oxygen,” Rahimi says, referencing most of us. Those who likely will benefit most from this expanded 24-hour window are unknown until they hit the door of a stroke center, says Switzer. These are patients where the physical exam, like Mendoza’s, may indicate that a lot of brain is immediately at risk. But additional perfusion tests currently run at MCG for patients arriving beyond the six hour window, show – unlike Mendoza – that the actual infarct area in the brain is not as bad because of collateral circulation some people are fortunate to just have. These small vessels continue to provide minimal support to some brain regions that otherwise would be in immediate jeopardy. They call this at-risk region the penumbra and while no one suggests waiting any longer than necessary, this part of the brain in these individuals offers some temporary protection until the culprit clot can be removed and blood flow restored. Switzer notes that this can particularly benefit patients who wake up from a night’s sleep to find they have had a stroke, a reality for about 1 in 7 patients.

“The DAWN trial gave us hope that we can help more people with clots back here,” Hula says, pointing toward the back of her 40-something head.

An aging population paired with unhealthy lifestyles like high-fat diets and little physical activity, mean the demand for these kind of services will only increase, Rahimi says. But plenty of potential patients already are out there waiting for well-tuned delivery systems to develop, Switzer adds. He pragmatically notes that many of those patients are now likely dead or confined to a nursing home.

Because he was not driving or alone, because his wife called EMS and because the Gold Cross paramedics brought him straight to the region’s only Advanced Comprehensive Stroke Center, stroke team members met Mendoza at the Emergency Department door and got a direct briefing from the paramedics. He got a CT to first check for bleeding and the extent of early damage, and then a CT angiogram so the contrast medium could identify the offending clot.

Kay had met Mendoza when her husband of nearly 28 years did not come home from a jog. David Gill was found on the roadside in a coma, but the quick EMS response did not help much that time. Horribly conflicted about ceasing life support for her 50-year-old husband, her then-chef instructor in Texas offered the wisdom of his father, neurologist Mendoza.

Mendoza and Kay would actually meet a year and a half later. They would just click and soon marry. They have great fun traveling the world whenever he is not working as a medical coding consultant, a neurologist at Augusta State Medical Prison or in North Dakota, or as a volunteer teacher at a Friday resident and student neurology clinic with 1964 MCG graduate Dr. James McCord. Kay so hoped that she had not lost him, too.

His extremities were moving again in no time but Mendoza was still having trouble talking. He drew a triangular graph of his chances of recovery and performed his own mini-mental status exam. He looked at his pre- and post-angiogram and reasoned that this guy was devastated. He was back at work two days after leaving the hospital.

Mendoza says he never needed official rehab, but did start his own regular cardio workout back in his basement near the scene of his stroke. “They did a great job,” he says of his colleagues at MCG, the day before he and Kay were heading out of town again to make room for Masters Golf Tournament visitors at their home.

“Now we will see how much longer we can go,” he adds. “Every day is a miracle day.”

- About 795,000 strokes occur in the United States each year and stroke is the fifth leading cause of death and a leading cause of adult disability

- 87 percent of strokes are ischemic, where normal blood and oxygen flow is stopped

- Risk factors include: High blood pressure, High cholesterol, Diabetes, Tobacco use, Physical inactivity, Obesity, Heart disease and Atrial fibrillation

- Aging, gender (more women than men have strokes) and race (minorities have a higher and earlier risk) are uncontrollable risk factors. So are a family history and a previous stroke or transient ischemic attack. 20-30 percent of the time, the cause is unknown, or cryptogenic, Tsappidi says.

- Stroke can mimic hypoglycemia, seizures, alcohol intoxication, drug overdose/toxicity, cerebral infection even a brain tumor.

- Most commonly used field assessment is the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale.

Facial Droop: One side of face does not move at all

Arm Drift: Arm does not move equally with the other

Speech: Patient has slurred speech, uses inappropriate words or cannot speak. With a severe stroke, like Mendoza’s, speech is lost.