Down-to-earth craniofacial surgeon has worlds to offer patients

Dr. Jeff James still remembers his reaction during his fellowship in cleft-craniofacial surgery when he prepared to perform surgery on a 10-week-old baby.

He and the surgeon overseeing the operation were assuring the infant’s mother that her baby would be in excellent hands during the procedure to correct his cleft lip and palate. The initial surgery at 10 weeks is generally the first step of a protocol to correct the birth defect in which the lip and/or mouth don’t form properly in gestation.

But despite their words of comfort, the mother was sobbing inconsolably. James certainly understood her apprehension about the surgery, but he was startled to find she was also in mourning. Yes, her newborn’s face was atypical, and she intellectually knew that the gaps in his lip and palate needed to be corrected. Yet it was the face she’d fallen hopelessly in love with for the past 10 weeks, and on a visceral level she couldn’t explain, she was heartbroken that it was about to change, even if for the better. She gazed at that face through tear-stained eyes one last time before kissing her infant goodbye.

“We see that reaction all the time,” James’ mentor explained as they began the surgery. “The moms love their babies just the way they are.”

James was incredibly touched by the sentiment. But what overwhelmed him even more was the mother’s reaction when they presented the baby to her after the surgery.

This time, her tears were nothing but joyful. Her baby’s defect had been corrected. He was now well on the road to a healthy future, free of a defect that otherwise likely would have caused respiratory, speech, feeding and social problems as he began his journey through life.

“That feeling changed my whole life,” says James, who joined the DCG faculty in December 2017 to help as many craniofacial patients in the Augusta area as possible.

And what an impressive resume he brings to the table. James, who hails from Plainview, Texas, laughs about his hometown, “People think they know what flat looks like. They have no idea. In Plainview, you can stand on a nickel and see Dallas [350 miles away].” But what Plainview lacked in topography, it made up for in excellent dental care as James grew up. His father and grandfather practiced dentistry in the area, and his mother was a dental hygienist. His sister became a dentist and married one as well.

So a dental career was the obvious choice for James as well — right?

Not necessarily. James vacillated between dentistry and medicine, then opted for both. After earning his undergraduate degree at Texas A&M University, he enrolled in dental school at the University of Texas. But the more he pursued the discipline, the more he gravitated toward surgery. After earning his dental degree, he went on to Louisiana State University, where he earned a medical degree and completed an oral surgery residency. “For so long, I’d been on the fence between medicine and dentistry,” he says. “Then when I discovered oral surgery, I realized this was the field that bridged the chasm.”

The curriculum, he acknowledges, was grueling, “but there was overlap with what I’d learned in dental school,” he says. “I studied nonstop, but I felt like I had a leg up in several areas. By the time I took my boards, I’d had hands-on experience with just about everything you could imagine. I’d seen it all.”

Still, “when I got into oral surgery, I knew I wasn’t done,” James says. “I immediately started seeking fellowship opportunities.”

He had met his future wife in Louisiana, and Aimee, who was studying to become a nurse anesthetist, fully supported his dream deferred. With her blessing, he went on to complete fellowships in cleft/craniofacial surgery and facial cosmetic surgery. “It’s funny,” James says genially, “because I remember complaining about a test once when I was a kid, and my dad said, ‘Look, tests will be a part of your life forever.’ I wasn’t convinced at the time, but I’m convinced now.”

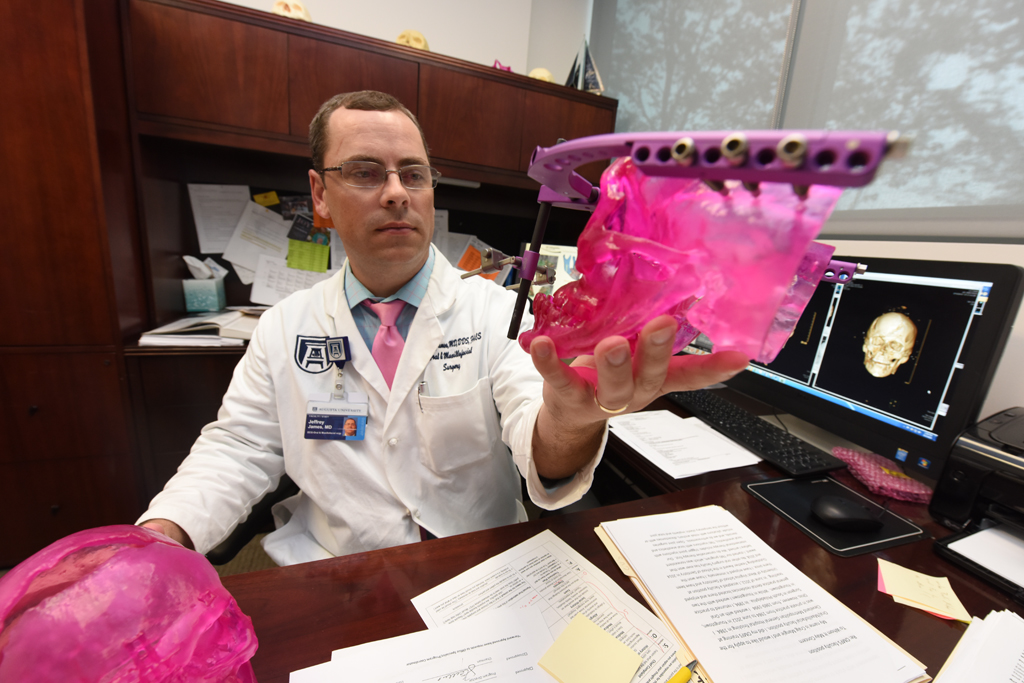

He anticipates being a lifelong learner, but James at last felt he had the education he needed to begin his career in earnest. When Dr. Mark Stevens in the DCG Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery recruited James as advanced education program director, James immediately set in motion his dream of a one-stop shop for patients — particularly newborns — with oral and craniofacial issues necessitating a multi-pronged approach to treatment.

His services include cleft and craniofacial surgery, as well as oral, trauma and cosmetic procedures for all ages. The DCG’s biggest selling point, in his estimation, is housing a multidisciplinary team under one roof — particularly important when dealing with parents of a child with birth defects. “We ideally start working with the parents during the pregnancy,” James says. “Craniofacial defects can be diagnosed as early as the second trimester, and we want parents to know we’ll be with them every step of the way. The educational component of our services begins immediately.”

Next, he and his colleagues — specialists in areas including neurosurgery, genetics, orthodontics, speech therapy, pediatric dentistry and psychology — huddle to create a long-term treatment plan. Many craniofacial defects, including clefts and plagiocephaly (in which the sutures of the skull fuse prematurely) require multiple surgeries and procedures over a period of years. But although James and his colleagues always have the big picture in mind, they counsel parents to take one day at a time. “Our team coordinator pulls it all together and removes the confusion for them,” James says. “All they have to concentrate on is their next appointment, and they come to the same location [for almost every visit]. Nearly every single dental specialty plays a vital role in treating craniofacial conditions, and we’re all right here together.”

James is more attuned to parents’ concerns than ever before; at press time, wife Aimee was expecting twins. “We are so excited,” he says. “I’m a small-town, down-to-earth guy — I’m just Jeff — and now I can relate to my patients better than ever.”

And he’s busy ensuring that with every passing year, he will have more and more to offer them. He is enrolling patients in several clinical trials assessing ever-improving treatment protocols, and he enjoys sharing the fruits of his education and experience with the next generation of dentists. He’s also busy spreading the word of his services, hoping referring physicians both locally and beyond come to find him a trusted and invaluable resource.

“The tough part is getting the word out,” he says. “The easy part is treating the kids. The most fun day of my life is a day spent with a patient.”

He prides himself on being enormously accessible — each patient or parent gets his email address, and he responds within 24 hours — and he allots one afternoon a week for unscheduled, “potential” patients. “My time is theirs,” James says. “There are so many walls these days between patients and providers. My mentor told me once, ‘Don’t ever let society put you on a pedestal that separates you from your patients,’ and I’ve never forgotten that. I’m all about making sure they can reach me directly.”

The payoffs, he insists, are enormous. “Kids with health issues seem to have the secret to life,” he says. “They go through surgery after surgery, but they have the best attitude.”

And as for their parents’ tears of joy upon seeing their child’s defect corrected? That’s just priceless,” James says. “Our goal is to send their kids out into the world without anyone ever knowing they had a problem.”

Can You Help?

The craniofacial work at The Dental College of Georgia is an example of the life-changing — and often life-saving — efforts unfolding daily on our campus. Your support will help us reach more patients than ever. It will also help advance our groundbreaking research, ensuring that treatment will continue to improve. To make a donation, or to discuss other ways to advance DCG’s mission, contact:

Rhonda Banks,

Director of Development

robanks@augusta.edu

706-446-4664