Just days after the killing of George Floyd, Kyle Goble, a second-year medical student teaching SEEP’s health disparities course, decided to break from his curriculum.

With protests and demonstrations still rampant, Goble had to give his students a safe space to talk and vent —about what was going on in the world, about health inequities they’d experienced and what it was like to live with the consequences, and most of all, just about taking this course.

2020 not only marked a year of significant racial unrest, but it was also the 50th year for SEEP, or Student Educational Enrichment Program, the Medical College of Georgia’s summer pipeline program for students from underrepresented, nontraditional and/or economically disadvantaged backgrounds. As a pipeline program, SEEP was designed to help solve racial issues in health care through simple addition: Better balancing the ratio of minority patients to doctors by placing more minority or economically disadvantaged physicians into practice.

For a decade or more, studies have confirmed that racial bias affects how doctors interact with patients. For example, a 2012 analysis reviewing two decades of published research found that Black patients were 22% less likely than white patients to get pain medication. In 2017, a six-year study by three California universities found that despite declining rates, racial discrimination is still the most common reason cited by Blacks for receiving poor service or treatment from a doctor.

Data from the Association of American Medical Colleges also continues to see an alarming lack of underrepresented students in medicine and other health professions. For example, compared to data five years ago, more male Black students were enrolled in medical school in the 1970s, according to the 2015 AAMC report “Altering the Course, Black Males in Medicine.”

Begun in 1970, SEEP is one of the nation’s oldest diversity pipeline programs, offering pre-college (in Augusta and Savannah) and intermediate and advanced college tracks. “The program has been doing this for a long time, so you would think over time, maybe we don’t need to do this anymore,” says Linda James, SEEP’s director for the past 17 years. “But this work is just as important, more so now, than ever.”

Fifty and counting

Goble’s health disparities course was possibly the first time that some students were able to speak openly about their feelings and fears about the world around them in a professional setting, and many reported it was one of their favorite parts of this past year’s SEEP program.

At the same time, some of us may have heard the term “minority tax” — when a minority person has the burden of extra responsibilities regarding achieving diversity. “Asking minority students to be in an academic space to talk about health inequity is an example of a minority tax,” says Goble.

“So really it was just an opportunity to debrief and vent about what it feels like to do this work.

“It was nice for me as well,” Goble adds. “I’d been feeling that minority tax burden significantly for the past several months in other ways than SEEP. So it helped me too…to take a pause and reflect on my emotions.”

At the same time, he says it’s important to understand that “they are absolutely going to feel that pressure and that pain. We’ve all agreed to give a little of ourselves to do this work, but it’s not a feeling to be avoided…It’s a decision you have to make yourself about how much to put on the line to fight for the truth and what you know and believe to be right.”

It can feel like a heavy responsibility for young shoulders, but as a mentor, James too talks to students about the power they have to go back into underserved regions to provide health care and make their contributions to improve health disparities and inequities.

“They have a role to help address that, to advocate for these injustices and inequities to go away,” says James, who is also assistant dean for student diversity and inclusion in the MCG Office of Student & Multicultural Affairs. “They have a right and responsibility to help effect change.” In fact, the SEEP program targets underserved regions of Georgia in recruiting participants, because these young people are most likely to understand the need and to eventually help meet that need, James says, and the national numbers back that up.

Made for the job

Growing up biracial in mostly white Arizona, Goble says he didn’t necessarily understand the historical context of health inequities then. But then he finished projects as an undergraduate and in graduate school on how biased health care negatively impacts the health of Black and brown people — in higher rates of breast cancer metastases in Hispanic and Latinx women; in challenges with access, contraception and abortion in Black women; and in the high prevalence of perpetual pediatric asthma clusters in historically Black urban neighborhoods. All of that was enough to jade him from his plan to enter medical school, since he couldn’t imagine being part of a profession that didn’t align with his personal values of equity and access.

Then, he moved to Georgia to take an administrative position with Morehouse School of Medicine’s pediatric residency training program. His program director, a Black woman, refused to let him give up on his original plan, especially with his broad experience in health inequities. She told him, “We need you. You have the heart and the mind for this work, and you can’t waste it. You’re obligated to participate in this movement.”

Goble followed her advice, took the MCAT, and was accepted to MCG, where he is now planning a career in pediatrics. Goble was seeking work during the summer between his first and second year when he heard about SEEP through a fellow student who recommended him to James for a teaching position.

James immediately asked him to teach the health disparities course, not only that, but to design a new curriculum. “She said, ‘Be creative. I trust you, you’ve been in this space and you know what you’re talking about.’ With her approval, I had the space that allowed me to deliver the content and message in a way that was genuine and spoke to students.”

He knew he didn’t want a course that just listed disparity after disparity without any explanation of why or how they came to be. He also didn’t want to “preach to the choir. Our students were from disadvantaged backgrounds…we live in these issues.” And being a couple months into COVID-19, he’d seen the data that suggested minority populations — Black, Hispanic and Latinx — were being disproportionately affected. Which begged the question: How was it that a brand-new virus that had only been around a few months was already showing the same patterns of disparities as heart disease, maternal mortality and HIV?

Goble focused his curriculum around three goals: 1) For students to be able to make the very important distinction between the concepts of health disparity and health inequity; 2) For students to apply critical thinking and understand root causes of health inequities, both historical and modern day; and 3) To provide students with a basic primer on how to communicate and advocate about health inequities now and later as a physician or other health care provider.

The last item was a doozy. “It’s an inherently controversial conversation,” says Goble. “It’s an inherently political conversation — all things American medicine tends to try to ignore or avoid. Now look at where that has gotten us as a medical system with implicit and explicit biases and actually covert racism and discriminatory practices.”

“No one helped us”

At age 16, Jada Henderson, ’23, was rushed by ambulance to the hospital. She and her mother huddled together in a room in the ER of what many consider one of the premier hospitals in the Southeast as doctors talked over them about her condition.

Henderson is Black. And she still recalls vividly how frustrated and angry she was — to be diagnosed with something that she didn’t understand, that wasn’t explained to her or her family, but that she was abruptly told wasn’t curable. “No one helped us … I felt very vulnerable in that moment,” she says.

“But it also ignited that dream of mine to help people.”

Henderson began telling everyone she knew that she wanted to become a doctor. In high school, Henderson achieved a 4.1 GPA and was one of 1,000 students out of 23,000 applicants to earn a Gates Millennium Scholarship, which supports high-achieving students with significant financial need, to pay for her undergraduate education. Her high school guidance counselor also connected her with SEEP.

Her first day, she thought, “Oh, no, I’m not going to make it.” But by the end, she says, “I could really say to myself: ‘You could become a doctor; this is tangible.’ I really credit SEEP for that.

“I had the opportunity to find out that all these people weren’t intimidating. It felt good to feel included in conversations. I hadn’t felt included inside medicine before that.”

While Henderson would prefer not to go into details, she is now getting help to manage her condition. Even so, that, along with the rigors of medical school, hasn’t stopped her from taking on leadership roles within MCG, including with the Student National Medical Association (SNMA). When it became public in May that Ahmaud Arbery had been killed just miles from MCG’s Southeast Campus in Brunswick, Henderson was among the students who met with administrators to discuss the importance of acknowledging these events.

She was also among those who helped organize the workshop “Courageous Conversations” to facilitate open discussion. “To me, it felt inappropriate to start the school year without discussing some of this,” she says. “The truth of the matter is that students come into contact with minority patients. The other reality is that at some point in time, all of us have been affected by our nation’s history. Whether good or bad or indifferent, it influences us, and whether we realize it or we don’t, it has created biases. There are a lot of classmates who are well-intentioned but who may be stalled as medical students because they don’t realize how race plays into medicine…. Racism is not just being sad because of microaggressions at work. There are real, live, physical consequences to race.”

“Courageous Conversations” would become a mandatory two-day workshop, held the first week of August 2020 during orientation for second-year MCG students, designed to help create affinity groups and diversity spaces where students can safely process, reflect, discuss and address racial injustice in relation to current events and medicine/health equity.

One slide in the workshop’s Powerpoint quotes the AAMC statement made on June 1 of this past year: “…the people of America’s medical schools and teaching hospitals bear the responsibility to ameliorate factors that negatively affect the health of our patients and communities: poverty, education, access to transportation, healthy food and health care. Racism is antithetical to the oaths and moral responsibilities we accepted as health professionals who have dedicated our lives to advancing the health of all, especially those who live in vulnerable communities.”

Delivering on the promise

SEEP ultimately delivers on its promise and on the crux of that oath: According to SEEP data recorded since 1978, more than 70% of its graduates have completed pre-medical/pre-health preparation and entered into a health profession. About 50% — nearly 600 individuals to date — chose medicine, matriculating at MCG and other medical schools throughout the country. The remaining students entered programs in dentistry, allied health, nursing, public health and biomedical graduate studies. “If students are successful in going on and matriculating into a health professions program, SEEP plays a significant role in enhancing their preparedness and competitiveness,” James says.

SEEP graduates like Dr. Jerthitia Taylor Grate, a 2002 MCG graduate and OB/GYN with a special interest in high-risk obstetrics and infertility, who went back to her hometown of Valdosta to practice medicine with her father, 1979 MCG graduate Dr. Samuel Taylor. Or the handful of SEEP graduates currently on the MCG faculty: Dr. E. Vanessa Spearman-McCarthy is a 2005 MCG graduate who completed a combined internal medicine and psychiatry residency program at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston; she has been honored by the Association of Medicine and Psychiatry for pioneering the unique pairing of the two specialties in an inpatient setting, and honored for her education of MCG students and residents as well as her humanity. Or 1991 Morehouse School of Medicine graduate Dr. John Lue, an OB/GYN, robotics expert and honored educator.

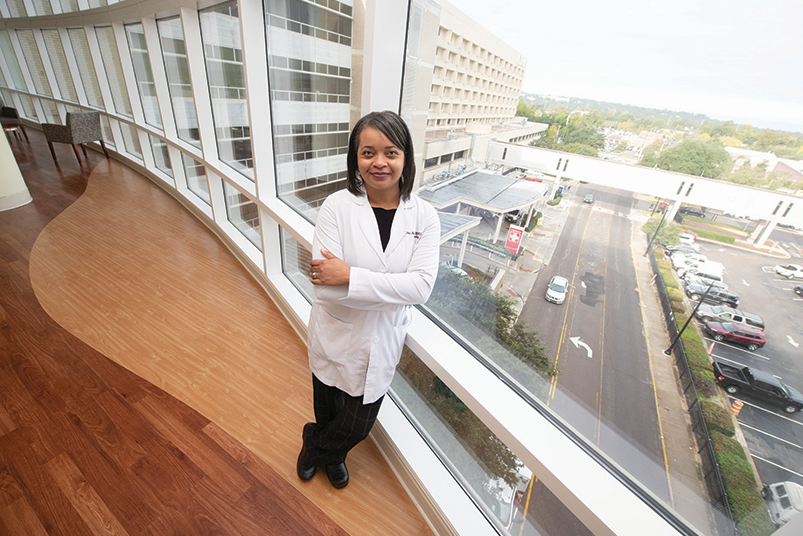

Or Dr. Sherita A. King, who went to medical school and did her urology training at MCG, followed by a sexual medicine fellowship at San Diego Sexual Medicine; today she is among a small number of Black female urologists in the nation, and her expertise includes male and female sexual function and incontinence.

Or like sisters Dr. Pamela Martin, a 2003 PhD graduate, and Dr. Debra Moore-Hill, ’07. Martin is a professor in MCG’s Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and a federally funded scientist studying diabetic retinopathy, who most recently was awarded a grant by Novartis for a clinically translational study of a new FDA-approved drug crizanlizumab (Adakveo) and whether or not it can prevent or reduce the frequency of sickle cell-related complications in the retina.

Moore-Hill is director of the adult neurology residency program, director of the continuous and prolonged ICU EEG program at Augusta University Health and a member of its multidisciplinary neuro-oncology clinic. As a neurologist, she specializes in epilepsy in pregnancy, epilepsy in women of childbearing age, and epilepsy secondary to neuro-oncological disease, and also cares for seizures in critical illness.

It was SEEP, says Moore-Hill, that “put the roadmap in front of us, and we were able to follow it.” Adds Martin: “I don’t know if I’d be where I am without SEEP.”

The two sisters grew up a few miles up the road from Augusta, in Harlem, Georgia. Their father was a factory worker, and their mother had planned to become an educator, but left school to care for their ailing grandmother. “But she was always so vocal about the importance of education,” says Moore-Hill. Adds Martin, “She was always pushing us — you can do anything, you can be anything.”

Martin says SEEP gave her not just confidence but also connected her with like-minded students, physicians and professors, which was affirming. “Before SEEP, I didn’t have the experience of knowing anyone who looked like me who was a physician and very few people who were college graduates,” says Martin, who was the first in her family to earn a doctorate and also teaches in SEEP’s biochemistry course every summer. “I had no knowledge of where do I even begin.”

Likewise, Moore-Hill provides clinical mentoring to SEEP students, a key part of the curriculum that allows students to shadow a health care practitioner. She says that SEEP pushed her. “When you’re at a smaller private college and you’re considered to be the smartest person, it kind of boxes you in a little bit,” she says. “Because you can grow more if you see peers who are also growing. So, SEEP was helpful for me to expand upon my academic skill. I had to study harder.” She gained significant traction and was able to distinguish herself even amongst the SEEP students, winning an award for the highest physiology course score one year and best research paper another year.

“It also helped me, in the time before social media, to see what other people with my aspirations were doing, and therefore what I should be doing to make sure my medical school application was more competitive. The SEEP program had lots of courses for MCAT preparation and networking. It just really provided a needed avenue to young doctors who looked like me…. I think often that’s the biggest barrier for younger kids wishing to pursue medicine. When you are knocking on that door, finding out who’s there to help you is important. SEEP opened that avenue completely for me.”

The way forward

Approximately 2,200 students who grew up with a dream of entering a health profession have found a pipeline through SEEP.

At SEEP’s inception in 1970, MCG was just three years past desegregation, during which Drs. Frank Rumph and John T. Harper became the college’s first two Black students. Yet, even as recently as the late 1990s, some classes could still count the number of minority students on one hand. Today, through concerted efforts by administrators such as Dr. Paul Wallach, who served as vice dean for academic affairs at MCG from 2012-18, incoming classes have reached closer to 50 to 60 Black and Hispanic students, out of a current class size of 240. While that number still is not reflective of the population of the state, it’s much closer. According to Georgia’s 2010 census, the state’s population is 30.5% Black, 8.8% Hispanic, and 3.2% Asian-American, with 4% from another race and 2.1% identifying as multiracial.

MCG’s numbers have dipped over the last couple of years because of reduced availability of scholarships for underrepresented in medicine students, James says. However, heightened racial tension over the past many months across the nation already has current Vice Dean Doug Miller and Dean David Hess enabling more support and conversations about the issues that minority students face, with the goal of more positive growth in both student numbers and scholarship in the near future.

Familiar faces

Dr. Folami Powell, who teaches in SEEP’s biochemistry course, has participated in research projects at MCG looking at humanism in the medical profession and identity. “One of the themes that comes up is the importance of having people that you can identify with in these positions,” says Powell, who is also a researcher and assistant professor in MCG’s Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. “In order to realize that this is something you are capable of doing and can aspire to be, part of that is having someone who looks like you in these positions.”

But that can only be the beginning.

Echoing other SEEP participants, Goble says that pipeline programs “are such a critical component and what we know to be necessary for solving these health inequities, specifically physician workforce diversification,” which according to some studies increases the likelihood of minority patients discussing health problems, improves the quality of notes taken by physicians, and could even close mortality gaps in area such as heart disease by up to 19%.

Because if it hasn’t been made clear already, diversity in medicine is not just a “feel-good” proposition. “We see the studies coming out in terms of newborn mortality and the difference that it makes when the physician is someone from an underrepresented population,” says Powell. “When you do have that influence and that person who is always there to speak up on issues that [otherwise] really aren’t brought to light, it’s a huge difference.”

She adds, “[But] it is challenging again to be the only person, the only one speaking up. The more that you have that representation, the less people feel like that pressure’s on them. Everyone wins from different programs in medicine being more diverse. Because we’re a diverse country — health care should reflect that.”

In an ideal world, pipeline programs wouldn’t exist. Nor, perhaps, would free clinics, scholarships for under-represented students, or the need for repeated conversations about race. “But we don’t live in an ideal world,” says Goble, “at least, not yet.”

The Spirit of SEEP

An oral surgeon in Warner Robbins, Dr. Vincent Carey, a 1991 Dental College of Georgia graduate, grew up in Macon, Georgia, in the 1960s and 1970s, in a rambling, four-bedroom house with his parents, his grandmother and his siblings — all 15 of them.

“We were the family on the other side of the track,” he says now with a bit of a laugh. From his grandmother, who was the family’s unofficial dentist, he learned the art of pulling a tooth without pain. “She’s the one, whose actions I witnessed, who steered me toward dentistry,” he says.

After high school, he attended Georgia College & State University, a time that he says was fraught with highs and lows.

At the predominantly white school, Carey faced microaggressions and racism on a level he’d never experienced before, culminating in an accusation of plagiarism by a professor, which Carey resoundingly disproved. Then the collegian completed the project again, on a different topic —“just to show them they weren’t going to stop me.”

But Georgia College was also where a friend introduced him to SEEP and to MCG. He was accepted, and while the work was challenging, the environment was refreshing. “The professors didn’t make it easy, but they cheered me on,” says Carey, compared to college, which was a morass of landmines and booby traps. “It gave me a new life; I was almost a beaten-down man [before]…then I was like a kid in a candy store…I can’t describe it. It’s something that you feel but you really can’t put it into words.”

It was a true turning point; everything from that point, says Carey, stems from SEEP. “SEEP prepared me for dental school [at the then-MCG School of Dentistry], so that I could represent SEEP and the dental school once I graduated,” he said.

Today, his sign may say oral surgeon, but he says he has an even more important job: serving as a bridge from his community into professional schools.

“This is not for me, to make money,” he says quietly. “This is because I care about my patients, I want them to be healthy. Also, the flip side of that is I want your children to see that if this is what they want to do, it’s possible.

“The oath we took the day we graduated from dental or medical school is to do no harm. Do no harm is not just to not cut somebody in the wrong place….they [patients and families] look at you as the guy who’s supposed to be a positive role model.”

To that end, Carey has established two scholarships for SEEP students who enter into health professions. First is the Thaddeus & Ira Chapman Scholarship for a SEEP student who matriculates into MCG, in honor of Carey’s SEEP classmate, the late Dr. Thaddeus Chapman, an OB/GYN and 1991 MCG graduate.

“If he had only $5, he’d find a way to give you $10 if you needed it,” says Carey. “He embodied the whole spirit of SEEP.”

The Jessie Kate and Vincent Carey Scholarship, for a SEEP student who matriculates into the Dental College of Georgia, is named both for himself and his grandmother, whose teeth-pulling expertise first captured his interest in dentistry. “Without her, I wouldn’t have been in SEEP. I wouldn’t have been in dental school, and I would not be here in Warner Robbins,” he says.

Other notable SEEP alums

Jabaris Demond Swain, MD, MPH

2006 MCG graduate

Cardiothoracic transplant surgeon-scientist and global health scholar, Perelman School of Medicine University of Pennsylvania

General surgery residency at Morehouse School of Medicine; NIH postdoctoral clinical translational research fellowship studying heart failure reversal using a novel gene therapy platform combined with cardiopulmonary bypass; completed one year as a junior clinical fellow in cardiovascular intensive care; earned an MPH at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health in clinical effectiveness; general surgery residency at Brigham

and Women’s; completed cardiothoracic surgery fellowship at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, followed by

an additional year of advanced fellowship training in cardiopulmonary transplantation and mechanical circulatory support

- Work focuses on augmenting access to clinical education and care delivery for cardiovascular disease within resource-limited settings like Rwanda

and Haiti - More than a decade with the nonprofit Team Health for annual travel to Rwanda to perform cardiovascular surgery and care for young adults and adolescents suffering from heart disease

- Served as a research advisor to the Rwanda Ministry of Health.

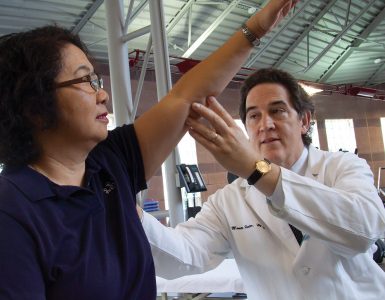

Lisa Cooper, MD, MPH

General internist, social epidemiologist and health services researcher Bloomberg Distinguished Professor, Equity in Health and Health Care, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Bloomberg School of Public Health

1988 graduate of the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill; internal medicine residency at the University of Maryland School of Medicine; fellowship in internal medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

James F. Fries Professor of Medicine, Division of General Internal Medicine

- Director, Johns Hopkins Center for Health Equity

- Pioneered research on how race and ethnicity affect health and patient care

- Designed innovative interventions targeting physicians’ communication skills, patients’ self-management skills, and health care organizations’ ability to address needs of populations experiencing health disparities

- 2014 recipient of the Herbert W. Nickens Award from the AAMC for outstanding contributions to promoting justice in medical education and health care equity in the U.S.

- Recipient of the Helen Rodriguez-Trias Social Justice Award from the American Public Health Association

- Member of the Maryland Health Care Quality and Costs Council where a special workgroup on disparities made recommendations leading to the passage of the Maryland Health Improvement and Disparities Reduction Act of 2012.

To establish your own scholarship for SEEP or to honor a SEEP mentor, contact Ralph Alee, executive director for major gifts at MCG’s Office of Advancement, at 706-721-7343 or email ralee@augusta.edu.

Editor’s note: While the impact of SEEP on the wellbeing of individuals is clear, the impact on the economic health of communities also is significant, with an estimated annual impact of $146.9 million, supporting 3,315 jobs and direct and indirect tax revenue of $24.3 million, according to an analysis completed by the consulting firm Tripp Umbach in 2020. 95% of these impacts are in Georgia.