Today, she’s the director of a National Institutes of Health office, but there was a time when Robin Boineau, ’90, wasn’t sure she’d even get into medical school.

She had the chops: Her mother, Dr. Barbara Boineau, was a clinical psychologist, and her father, Dr. John Boineau, was a cardiologist and arrhythmia researcher at Duke University. And she’d always liked medicine. Still, “I’m a cautious person by nature,” Boineau says. “I tend to be more pragmatic, and it’s not easy to get into medical school.”

It took the Medical College of Georgia to get her back on track.

After her parents divorced, Dr. John Boineau moved to Georgia and joined the faculty at MCG. Soon after Boineau graduated from University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, her father arranged for her to meet with MCG’s admissions director, Dr. Boyd Sisson, to assess her chances. Six of his words changed the course of her career: “You might be a good candidate.”

It was just enough encouragement. After graduating from MCG, Boineau completed an internal medicine residency at Brown University and a cardiology fellowship at Duke University. She interviewed for three possible jobs—at a private practice in Dallas, an academic position at Stanford University, and at NIH. Boineau’s first job after training was with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in the Division of Epidemiology and Clinical Applications, where she was a medical officer, initially overseeing large epidemiology studies and, after four years, switching to large NIH-funded clinical studies. With an NHLBI reorganization, she joined the Division of Cardiovascular Diseases and continued working as a medical officer to oversee both large clinical studies and basic science research related to heart failure and arrhythmias.

Now, this past October, she was named director of the Office of Clinical and Regulatory Affairs (OCRA) at the National Institutes of Health’s National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, where she helps oversee more than $150 million dollars in funding for priorities as diverse as pain and mind-body approaches, natural supplements and diet, the microbiome, and whole-body health.

MCG, she says again, is what got her here.

A great education

As a student, Boineau says she “liked to be a wallflower” — just put her head down and work. “It was hard work,” she says, “but I learned, and I was ready when I got to my residency.”

She remembers acutely the “great education” of her first two years of introductory courses as well as the nurses at the Charlie Norwood Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center — “They made sure you knew how to draw blood.”

Other moments that stand out include her third-year rotation with a family practice in Jesup, Georgia, and the late Dr. Ollie McGahee Jr., ‘58, a “brilliant doctor,” who by his unassuming demeanor combined with excellent communication skills taught her the value of humility and how to be a good communicator.

She also remembers her surgical rotation at Memorial Hospital in Savannah, where the chief resident Dr. John Hungerpiller taught her one of the most difficult parts of a doctor’s job: how to talk to family members when their loved one ends up dying. And although she was likely assigned the least intense room with the most senior nurse at Memorial’s trauma center, she also remembers the responsibility of being told, “This is your patient; you need to find out what’s going on.”

“That was helpful to learn, how important it was to feel responsible,” she says, “not to feel like somebody else was in charge but that it’s your job to be very thorough and not assume somebody else is going to do this.”

There were many experiences like that along the way, says Boineau. “I felt really that MCG prepared me for becoming a physician and taking care of patients as well as thinking scientifically,” she says.

“We were expected to learn information and get tested on it, retain it and then apply it, both in the classroom and in the medical setting. And that’s true for research. When you do research, you have to know when you see something different, and you have to be able to say, ‘This is a different variable, why is this different,’ and start going down that road.”

For the greater good

It’s a cool spring morning in Washington, D.C., and Boineau is sitting at her computer, while behind her, through the windows of her home near the National Cathedral, the first early blossoms are starting to peek out.

Boineau is still mostly working from home due to the continued impact of COVID-19. Just a few months into her new position as director of OCRA, she can’t help but draw the line between the pandemic and her work now.

For the general public, complementary and integrative health tends to connote the idea of supplements or massage therapy. OCRA does indeed conduct research in areas such as nutritional interventions and mind and body approaches. But a huge area of interest is whole person health, which involves health restoration, resilience, disease prevention and health promotion across the lifespan. In a time of pandemic, it resonates.

“A lot of the [NIH’s] institutes and centers are focused on diseases, and so I think this focus on health and wellness and resilience is really an important focus,” she says, “for making sure we don’t think about only treating disease, but also what can we do to make sure we have a healthier population and what are the resources people should be focusing on.

“It’s going to be a really big thing for the federal government and the NIH to tackle: What can we do to reengage people in understanding the importance of public health and how what you do affects your neighbor. I think we really saw that with the pandemic.”

While Boineau has stepped back from her own cardiovascular research — she’s currently helming a slimmed-down portfolio of just two studies — she says the director role only amplifies what got her interested in research in the first place: the ability to improve treatments and positively impact patients.

She chose to work at the NIH, she says, for two practical reasons: First, her friends in the Class of ’89 at MCG, already in a practice, were sharing their frustrations with practice culture due to changes in reimbursement. “As they got hired into practices, they were expected to work really hard, you had less time to spend with your patients and got less reimbursement,” she says. “Because I like to be so thorough, I was really concerned about having to push patients through really quickly.”

But the biggest reason for moving to D.C. was this: “You can help people in clinic, but if you can advance the science, you can help more people.”

During her career at NIH, she says she has had the good fortune to be part of several large projects that have become evidence-based medicine.

For example, Boineau was engaged in multiple studies that changed clinical practice. In the 2005 SCD-HeFT (Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure) study, researchers found that ICDs, or implantable cardioverter defibrillators, reduced mortality by 23% for patients with reduced dysfunction congestive heart failure — hearts that have difficulty pumping. That was compared to the heart rhythm medication amiodarone or placebo.

She also conceived and was the NIH lead on TOPCAT (Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function Heart Failure With an Aldosterone Antagonist Trial), aimed at patients with hearts that have difficulty relaxing to allow filling of the heart between beats. Considered a negative study, it found a fourfold difference in results between patients randomized from Russia and neighboring Georgia and those enrolled from the U.S., Canada, Brazil, and Argentina, who saw benefits. The FDA is now considering approval for the study drug based on those findings in North and South America.

And she was part of the FREEDOM trial, which examined the efficacy of drug-coated stents compared to bare-metal stents for patients with diabetes mellitus and multivessel coronary artery disease — and found bypass surgery was superior to percutaneous coronary intervention using stents.

At the same time as FREEDOM, Boineau was also part of the TACT, or Trial to Assess Chelation Therapy — part of a push by Congress that was expected to debunk chelation, a controversial therapy that removes metals from the body, used for over 50 years by a minority of practitioners to treat symptoms of cardiovascular disease. The study, led by both NHLBI and NCCIH (then known as the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine), was “widely expected to drive the final nail into the coffin for chelation therapy,” according to an expert analysis of the study by the American College of Cardiology. But the positive results “stunned the cardiology community that this worked,” says Boineau. The study is now being replicated in TACT2 in patients with cardiovascular disease and diabetes with results expected in 2023.

The chelation study is one project Boineau continues to be involved with. But while it has made her own research portfolio smaller, the opportunity at OCRA has expanded her horizons in other ways. Boineau describes herself as a lifelong learner, and during her time at NIH, she had long conducted explanatory clinical trials, which control who is randomized into the study to increase the likelihood of a difference between active and placebo groups. The NCCIH’s focus on pragmatic clinical trials conducted within health care systems — which include a wider patient population under real-world conditions, with fewer selection criteria —“was a growth area for me.”

As OCRA’s director, Boineau is also working with NCCIH-funded researchers to ensure their study design is sound, that the question being asked has the proper number of patients enrolled, and that study methodology is optimal, to ensure that the highest-quality data is produced and subsequently published in high-profile journals.

It all goes back to her unofficial mantra: “When you advance the science, you help more people.”

“The other point that I’m often not able to make when I talk to people [is this],” she says. “My dad was an NIH-funded investigator, and I saw how hard he worked. I really want to feel like I grease the wheel for the researchers. I’m there to make sure that what we are planning on doing is clear, that we all understand clearly about why it’s important to collect this information, how it’s going to help the final study in the long run. That experience of having seen my dad and his colleagues be really diligent researchers has really been valuable in understanding how hard these researchers are working behind the scenes and my wanting to be as helpful as possible.”

——————

Family Ties

As the daughter of Dr. John Boineau, Dr. Robin Boineau had a great role model. Her father, who passed away in 2011, is considered a pioneer in the development of the surgical treatment of Wolf-Parkinson-White syndrome, a heart condition that can lead to episodes of rapid heart rate. He also developed the Cox-Maze procedure, a surgical treatment for atrial fibrillation, in which the heart rhythm is irregular and too fast. And he was the author of The ECG in Multiple Myocardial Infarction and the Progression of Ischemic Heart Disease, a textbook which is considered a classic in the field.

As the daughter of Dr. John Boineau, Dr. Robin Boineau had a great role model. Her father, who passed away in 2011, is considered a pioneer in the development of the surgical treatment of Wolf-Parkinson-White syndrome, a heart condition that can lead to episodes of rapid heart rate. He also developed the Cox-Maze procedure, a surgical treatment for atrial fibrillation, in which the heart rhythm is irregular and too fast. And he was the author of The ECG in Multiple Myocardial Infarction and the Progression of Ischemic Heart Disease, a textbook which is considered a classic in the field.

Along with Duke University and MCG, he served on the faculties at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and Washington University in St Louis.

————————

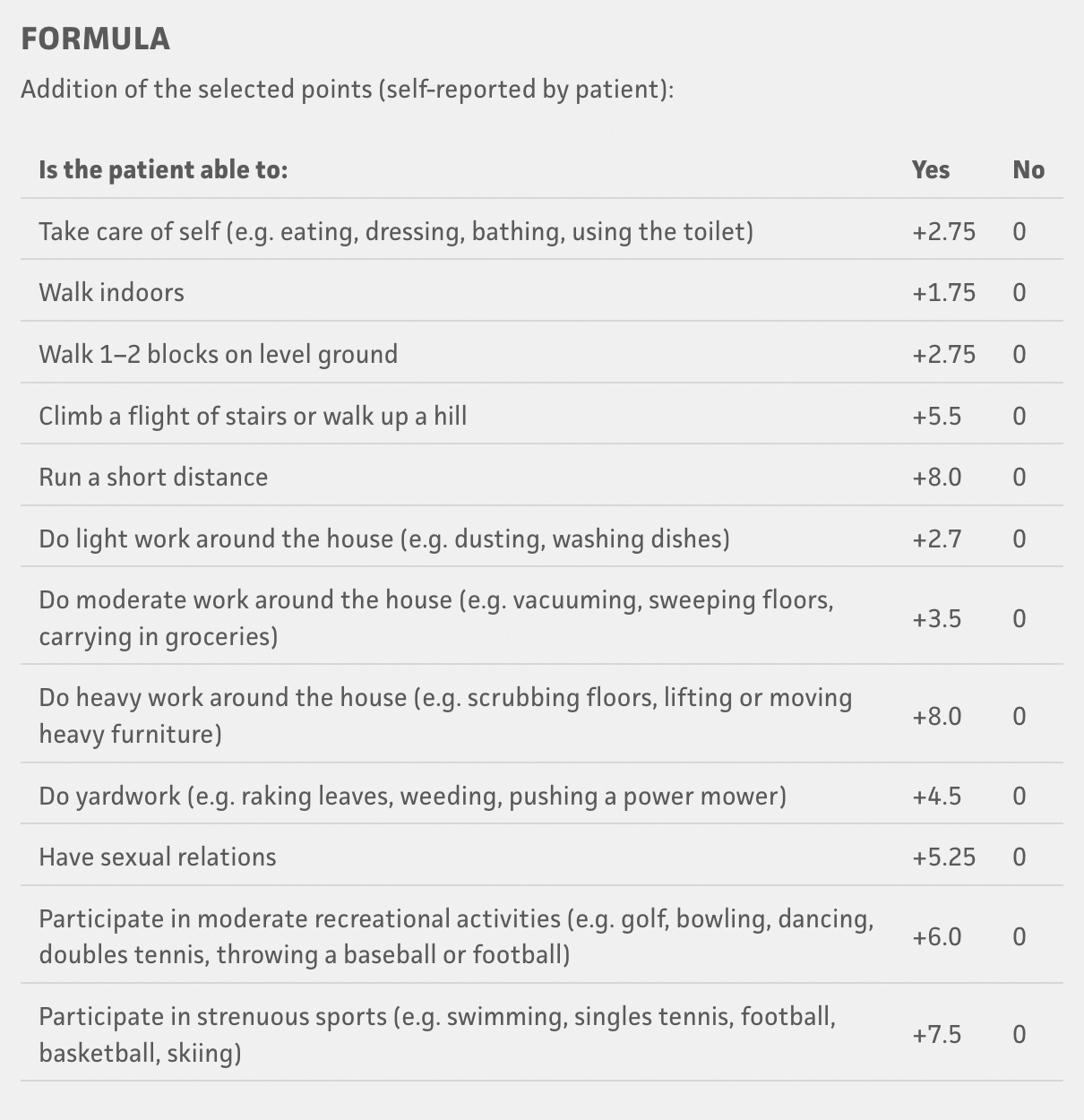

Growing DASI

Dr. Robin Boineau is also recognized for a project she worked on before she ever applied to medical school.

The Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) has been translated into multiple languages and is widely used today as a self-reported patient questionnaire to estimate the heart’s functional capacity during exercise, since decreased exercise capacity is associated with worsening health. But back in 1983, it was just an idea by a core group of Duke University cardiologists — Dr. Rob Califf, now Commission of Food and Drugs at the U.S. Food & Drug Administration; Dr. Mark Hlatky, now professor of Health Policy – HP/Health Services Research and Professor of Medicine – Cardiovascular Medicine, at Stanford University; Dr. Michael Higginbotham, now in private practice in Cheyenne, Wyoming — and several biostatisticians, Dr. Frank Harrell, professor of Biostatistics at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, and Dr. Kerry Lee, emeritus professor of Biostatistics & Bioinformatics at Duke University.

The group would later become the Duke Clinical Research Institute. They hired Boineau, fresh from a master’s degree in exercise physiology from the University of Georgia, to develop the initial questionnaire. She did the leg work, developing an approach based on different activities that people might regularly do, interviewing people undergoing exercise testing at Duke, conducting statistical analysis to narrow it down to the best questions, then conducting further interviews to test the final questionnaire’s validity.

Boineau had about 15 people left to interview before she had to move to Augusta for medical school. “It was a great way to utilize my skillset while applying for medical school,” she says. “I didn’t know it was going to turn out to be as valuable a tool as it did for researchers.”