For Fox News journalist Benjamin Hall, who in March was lying in a hospital bed in Kyiv, Ukraine, with multiple severe injuries, the grizzled man with the salt and pepper hair had to be one of the most beautiful sights he’d ever seen.

That man was Dr. Richard Jadick, who’d just driven 12 hours past multiple Ukrainian and Russian checkpoints on a rescue mission organized by Save Our Allies. The mission: To retrieve Hall, who had been injured during an attack on a car that killed Fox News cameraman Pierre Zakrzewski and Ukrainian journalist Oleksandra “Sasha” Kuvshinova.

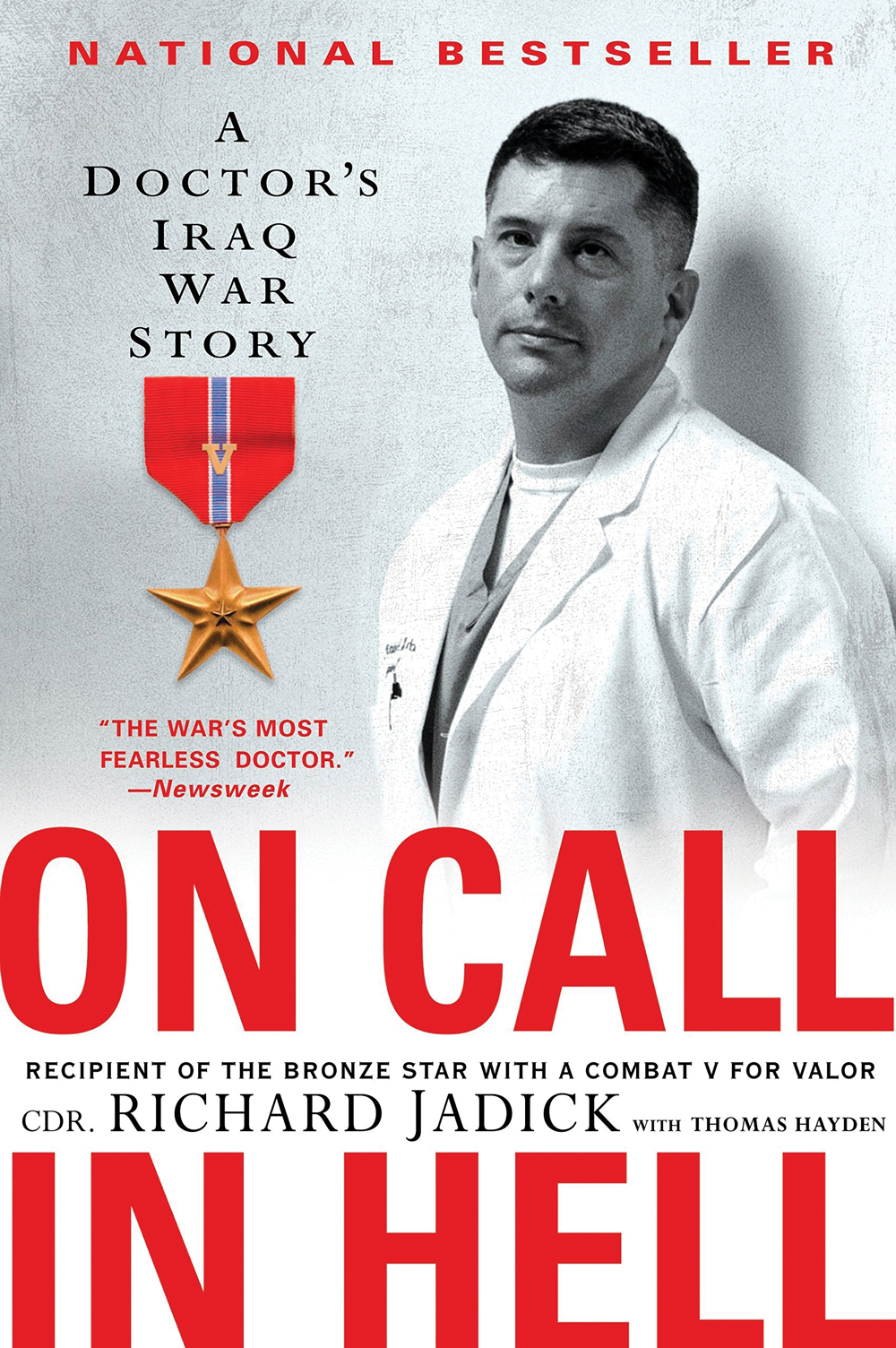

Jadick is a urologist at Wellstar Health System and completed his urology training at the Medical College of Georgia and the AU Health System in 2009. He has other titles too: Marine, Navy doctor, Bronze Star with Combat V for valor recipient, author of On Call In Hell, motivational speaker. Then there are those he shrugs impatiently at: war hero and the “world’s most fearless doctor” — for saving at least 30 soldiers during the height of the battle of Fallujah during the Iraqi War in 2004.

I don’t know about that, he says: “I just showed up, just like everything in life. That’s what it’s about.”

How Long Before We Can Get Out of Here?

Inside the thin walls of the rattling old ambulance, Jadick was cold. It was March and 26 degrees, and he’d been asked by an old friend at Save Our Allies, a nonprofit that rescues and aids Americans and allies in war-torn environment, to assess refugee sites in Poland for Ukranians fleeing the Russian attack. He was working on a plan to help transport the wounded out of Kyiv, Ukraine’s capital city, when he got the call that his expertise was needed to rescue Hall.

He and Dakota Meyer, a Marine and Medal of Honor recipient also involved in Save Our Allies, drove six hours north to the Baltic Sea to pick up the old ambulance, then drove it nine hours back to Poland. Then Jadick, two contractors and a Ukrainian translator boarded the vehicle. Once they were inside the Ukrainian border, they went to their first stop, a safe house inside an ornate Russian Orthodox church, to be briefed.

With a top speed of 40 kilmeters per hour — just 24 miles per hour — the trip would take the men 12 hours, with multiple stops at checkpoints. “We didn’t want to get into the Russian checkpoints, and we weren’t sure how the Ukrainian checkpoints would go too,” says Jadick. It was a repeat of getting out of the ambulance, being frisked, and having soldiers search through the vehicle. With the translator’s heavy Russian accent, the goal was to limit how much he talked. So Jadick had to say, again and again, “I’m a doctor, we’re bringing medical supplies.”

At one point, the vehicle broke down at a checkpoint, with Ukrainian soldiers standing close by with guns and watching them. As the contractors sweated over the engine, the men could only crack sarcastic jokes to lighten the tension: “I’m like, you guys are supposed to be super-secret squirrels, how come you can’t fix this thing?” Jadick said to them.

They challenged him to tell them what was wrong. “It’s broken,” Jadick told them, and they swore in return.

“You laugh — a lot,” he adds. “I never felt in danger, but I always felt like this could escalate quickly into something bad”— so there was that nervousness.

The roads, too, were challenging, bombed out and packed with mortar rounds. Every so often, they’d pass ruins and see artillery going off, and would have to figure out another road in. And always, always, was the steady westward flow of cars leaving Ukraine to find safety.

But they made it.

At about 11 p.m. in the city hospital at Kyiv, Jadick met the orthopedic surgeon who was managing Hall’s care during the day and holding a weapon at night to protect the building. Then, Jadick went upstairs to check on Hall, who was “pretty banged up.” Hall looked at him and said, “How long before we can get out of here?”

“I think we’re leaving in the morning, 11:30,” said Jadick. The plan was for him to assist the Ukrainian surgeon with an operation, then evacuate.

Jadick had already scrubbed up when the word came from one of the contractors: “Listen, it’s no good. We’re not staying here. We’re out. So pack him up.”

Intelligence had come through that Kyev and its hospital were being targeted. So, the team devised an evacuation plan. Then, it was 12 hours back on those roads, with Jadick carefully protecting Hall from further complications from his many injuries, which included a skull fracture, shrapnel embedded in his neck, and a mangled hand and leg.

They were able to meet up with Ukrainian special forces and Polish special forces. Then Hall was transported by Blackhawk helicopter to a Polish hospital where Jadick worked on him, then to Landstuhl Medical Center in Germany and finally to Brooke Army Medical Center in Texas.

From his hospital bed in April, Hall tweeted, “To sum it up, I’ve lost half a leg on one side and a foot on the other. One hand is being put together, one eye is no longer working, and my hearing is pretty blown… but all in all I feel pretty damn lucky to be here – and it is the people who got me here who are amazing!”

My Job Is To Use What I’ve Been Given

Jadick is 56 this year. When he volunteered to join the Marine unit in Iraq, he was 38.

“Volunteer is a weird word,” he says, “because it’s just knowing that you have something you can bring to the table and you shouldn’t sit at home if you can do it better. That’s the way I thought” — and the way he still thinks. “Listen, I truly believe God has given me a bunch of stuff. My job is to use it.”

“Volunteer is a weird word,” he says, “because it’s just knowing that you have something you can bring to the table and you shouldn’t sit at home if you can do it better. That’s the way I thought” — and the way he still thinks. “Listen, I truly believe God has given me a bunch of stuff. My job is to use it.”

As a kid, Jadick’s idol was “Hawkeye” Pierce, the fictional doctor on the TV show MASH. “I liked movies of war, but I never wanted to go out and kill people,” he says. “I always thought being a doctor and taking care of a unit was pretty cool.”

Joining the Marines was his “in” to pay for college. He then served for six years, never thinking he’d get into medical school. “I was never smart enough,” he says. But, “no guts, no glory, so I put in my applications.”

His military experience helped him ace his interviews, and he graduated from the New York College of Osteopathic Medicine in 1997, this time through a scholarship with the Navy’s Medical Corps program. He finished a residency in osteopathic medicine in Bethesda, Maryland, with the National Capital Consortium Program, and when 9/11 happened, he knew he wanted to serve overseas.

The Marine Corps doesn’t have its own doctors, but contracts with the Navy to provide them. So, the Navy doctor went back to the Marines.

His first tour of duty was in 2003 in Liberia and Monrovia during the shelling of the Liberian embassy. A year later, the First Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment was desperately looking for a doctor to join a mission in Iraq.

Jadick signed up. The mission would become known as the Second Battle of Fallujah, described by U.S. military as “some of the heaviest urban combat U.S. Marines have been involved in since the Battle of Huế City in Vietnam in 1968.”

His wife, Melissa, was nine months pregnant with daughter MacKenzie at the time; Jadick was also just about ready to start another residency in urology. But, “you want to be part of something bigger than yourself,” he says.

The battle was unlike anything Jadick had experienced before. On the first day of the attack, he quickly realized that his aid station at the base camp six miles outside of the city center — a 45-minute drive — was essentially useless. “These guys die quickly,” he says. There is no Golden Hour — “If this guy’s shot, he’s going to bleed out in 10, 5 minutes.”

In a combat scenario, “you have to be as far forward as possible…there’s no time, you have to be right there if you want to intervene.”

Jadick swiftly made the decision to move into the heart of Fallujah, where he would be five minutes away from Marines under heavy gunfire who might need emergency medical attention. He took an armored personnel carrier, a gun team of four vehicles and a pack of medical supplies on his back about the size of an office chair. Then, “We rolled into an ambush,” he says. “We were in the kill zone.”

At one point, Jadick exited the vehicle to help get a couple of patients loaded. Head down, focused on the men, he didn’t see the two insurgents loading a rocket-propelled grenade, aiming it straight at the back of the vehicle from 50 meters down the road. His gun team intervened, and the rocket skimmed off the top of the carrier. “You just rely on them to do their job, and I’m supposed to do my job,” he says.

As the battalion surgeon, Jadick’s decision to place his aid station in the midst of the battle of Fallujah, where he could quickly pack the wounds, stabilize the men and get them out, has been credited for saving the lives of at least 30 Marines. “I had never seen a doctor display the kind of courage and bravery that Rich did during Fallujah,” said Lt. Col. Mike Winn, the executive officer for 1st Battalion, 8th Marine Regiment, who nominated Dr. Jadick for his Bronze Star, during an interview with The Augusta Chronicle in 2006.

Jadick remembers it differently. When asked what stands out for him from those days, he pauses, then says, “The death.” He pauses again, and his voice breaks. “The guys who you don’t save. Body bags — putting people in body bags. That resonates with me every day.”

For the lives he saved, he prefers the words “help” or “assist.” “You do as best you can, then get out, and they do well,” he says. “That’s a positive.”

He also thinks about the confidence and training he was able to instill in the corpsmen who worked side by side with him at that aid station, under heavy fire. “I always used to say this: When there’s a wounded Marine on the street, what’s supposed to happen? Well, you need to get the right people at the right time to the right place. And the right place is right there, on the street. The right time is as fast as possible, not within a golden hour, not within 10 minutes, if you can get there in one minute, that’s when you should be there. And the right people are the most experienced.”

Jadick says when he left Fallujah, “it was those guys. So I was pretty proud of that.”

Whatever You Do

Jadick retired as a commander from the Navy in 2013. It can be more difficult to move up in the ranks when you often deploy as a medical specialist for other branches of the military. So he came home to the state he fell in love with during his urology residency at MCG, joining Piedmont Newnan Hospital and its urology group and, more recently, Wellstar.

The field of urology attracted him because of the patient population. “In urology, I can cure cancer,” he says. “I can fix your problem…Let’s make you pee better. That’s easy, I can do that. Or let’s cure your kidney cancer. I’ll take out the kidney and you’re done. You don’t have cancer anymore.”

He says he considered trauma at one point, “but I had enough of trauma.”

His goal for the next five years is to grow the urology program at Wellstar as the place for urology patients living on the south side of Atlanta. At that point, he and his wife, Melissa, a pediatrician, will be empty nesters, with children MacKenzie, 18; Eva, 15; and Gregory, 13, all in college. “What am I going to do as a grownup?” he says. “I don’t know.”

He doesn’t necessarily want to run for office, but he’s considered being part of the political process at the local or state level. Or, he could go back into nonprofit work, which he did for several years at The Independence Fund, an organization that works to improve the lives of veterans who are catastrophically injured or ill.

“It’s about giving back,” he says. “Helping people, being a part of the community, being a positive influence on those around me is something I try to do. I am never perfect at it. I always fall short. I do try, I stumble, I get back up, I put another foot forward.

“Imperfection is kind of the hallmark of everybody. But what do you do with that imperfection?”

I’m Already In Iraq

Jadick was on a ship coming back from his first deployment when he found the Medical College of Georgia online. At the time, the Section of Urology, headed by Dr. Ronald Lewis, was looking to add another two residents a year, but the positions were not yet funded. Jadick says he thought, “If the Navy pays for me to go, maybe they’ll take me.”

Jadick hit it off with Lewis and with faculty member Dr. Art Smith, a former Navy captain, during his initial interview. He got the offer a few months later, but he told them, “I’m already in Iraq” — with the battalion in Fallujah. MCG hoped he could start in July or August, Jadick thought it might be September or October, but it wasn’t until the following March before he returned stateside.

MCG held the position for him.

“I’ll never forget what MCG did for me,” he says. The training was hard work, he says, but it “was amazing. It was exactly what I needed. It gave me enough autonomy with some guidance. …We suffered, but when I say we suffered, we enjoyed every minute of it.

“Because your suffering, it just brings out a very fun, humorous sense. You’ve got to work, you’ve got a mission, but you’re there with people you like and people you respect and people who are teaching you things. It was just a good amalgamation of all of that.”