The problem is complex, but the math is simple — and the state’s public medical school hopes it equals more primary care doctors for underserved Georgia.

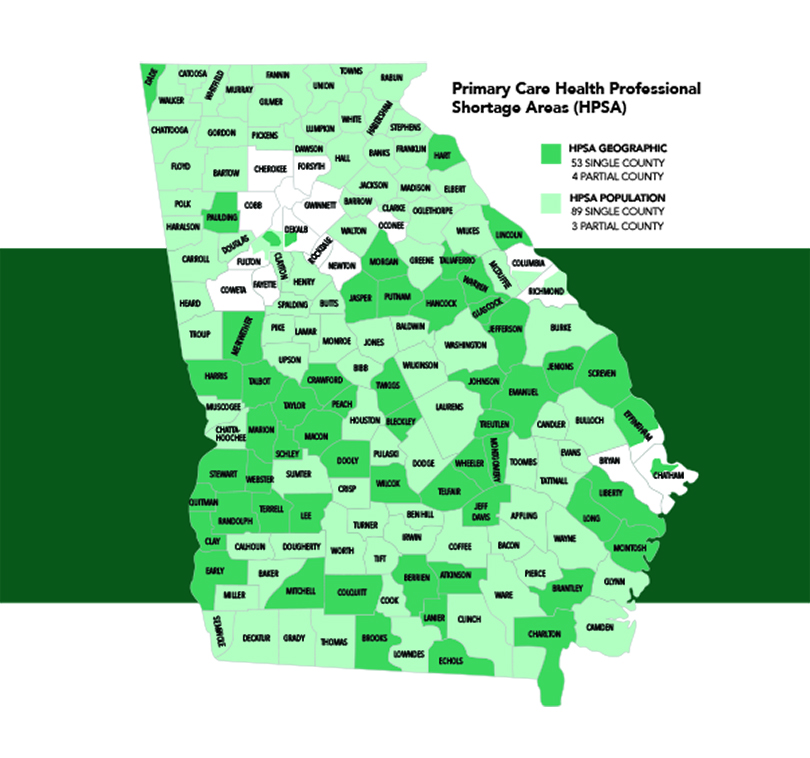

Eighty-nine of Georgia’s 159 counties are designated Primary Care Health Professional Shortage Areas by the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration. That means there aren’t enough doctors to treat the people living there or near there; the numbers of women lost to pregnancy-related deaths and babies who die before their first birthdays are higher than average; and the people who live there are poor — living 100 percent or more below the federal poverty level.

About 3.2 million Georgians live in a designated shortage area and the state would need 672 new doctors to move to those areas to alleviate the current deficit, according to research by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

To help reduce the problem, MCG is proposing a new curriculum that it hopes will ensure the areas of the state that need new doctors the most get them.

The proposed 3+ Track will allow an eventual 50 students per class to finish medical school in three years, go directly into a residency program in family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics/gynecology or general surgery in Georgia and then commit to six years of service in an underserved area of the state. If they do so, their tuition to medical school would either be free or their student loans would be forgiven.

While a three-year accelerated curriculum is not novel in the nation, it’s something MCG’s administration says the medical school is perfectly positioned — and needs — to do.

“While we have one of the largest medical school classes in the country (at 230 students per class) and a significant number of our students go into primary care, we don’t have as many entering primary care in Georgia — especially in underserved Georgia — as we would like,” says Dr. D. Douglas Miller, MCG’s vice dean for academic affairs.

In the 2019 MCG Match, for example, 164 students matched to primary care residencies, but only 27 of them matched with primary care residency programs in Georgia. “As the state’s only public medical school, we have to think about how to address that issue because it’s part of our mission and our responsibility.”

The Problem

There is a crisis, particularly in underserved Georgia.

Eight counties have no doctor, 11 have no family medicine physician, 37 have no internist, 63 no pediatrician, 75 no obstetrician/gynecologist and 78 no general surgeon.

The health statistics for the state are proof of the impact – four of those eight counties rank in the lowest quartile of the state for health outcomes, which measure things like life expectancy, maternal and infant mortality rates, and number of deaths from chronic diseases like diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

The problem is only expected to worsen as the country’s population ages, more physicians reach retirement age and government insurance programs like Medicare and Medicaid place more and more importance on value-based care — keeping people out of hospitals, preventing hospital readmissions and dealing with chronic illnesses on an outpatient basis.

“That requires more primary care physicians,” Miller says. “Not more (sub)specialists.”

It’s both a public health and economic issue — people without access to health care often put off preventive care and when they do show up in the system, they are the sickest of the sick and costs to treat their complex health issues skyrocket.

“Studies show that for every primary care physician you add, you save millions in health care costs,” adds Dr. David C. Hess, MCG dean. “You find disease earlier and you prevent disease when care is not haphazard. Studies have shown that having more primary care physicians is associated with lower mortality rates, never mind better quality of life.”

Doctors working in underserved areas of the state save Georgia around $56.5 million in health care costs each year, according to research by Tripp Umbach, a recognized leader in health research, strategic planning, economic analysis, feasibility studies and market research.

The problem is also an economic development one, says Daniel Dorsey, external affairs coordinator for the Georgia Board for Physician Workforce, which works to identify and meet the physician workforce needs of Georgia.

“When a physician establishes a practice, they bring around 10 jobs with them, which is a huge economic driver for what could be a small area,” he says. “When larger companies are taking a look at places to establish new sites, proper economic climate is a big factor. If these rural areas don’t have a health care infrastructure, companies may pass on investing in that county. We have to have a healthy workforce there and one way to do that is making sure there are practitioners there to take care of the population.”

According to Tripp Umbach’s research, the economic impact of doctors in underserved Georgia is $84.8 million annually now. With their projections for needed physician growth that could reach $347.3 million by 2028.

A Proposed Solution

For its part, the Georgia Board for Physician Workforce works closely with other state agencies like statewide Area Health Education Centers to develop a physician pipeline by targeting students in underserved and rural areas early and often.

For its part, the Georgia Board for Physician Workforce works closely with other state agencies like statewide Area Health Education Centers to develop a physician pipeline by targeting students in underserved and rural areas early and often.

“It’s a concept of growing your own physicians,” Dorsey says. “AHECs around the state do an incredible job of engaging high school and college students that are interested in a career in the health sciences. We have to engage them and cultivate that interest early, help these students become health professionals and then return to these critical shortage areas. The state invests millions of dollars in medical education and we want to see a healthy return on that by keeping doctors here to practice.”

The board also incentivizes working in an underserved or rural area — defined by a population of 50,000 or less (about 120 Georgia counties) — by providing physicians with $25,000 in student loan repayment per year of service, up to four years. The retention rate of physicians who participate in that program is around 70 percent, Dorsey says.

At MCG, officials hope for similar numbers with the implementation of the 3+ Track, and they say the timing could be no better.

The premise is three-fold, Miller says:

1. Increasing the number of MCG students who pursue primary care residencies in Georgia.

2. Taking better advantage of MCG’s statewide campus model, which helps by exposing students to opportunities in rural and underserved communities and has helped build a network of connected community hospitals, community-based physician groups and health centers. “Our statewide education network is now more than a decade old and our campuses across the state create an opportunity to think differently about how we can take MCG and our state to the next level,” Miller says.

3. Adding a primary care curriculum track. MCG has already demonstrated the ability to run concurrent curriculum tracks, like the Northwest Campus in Rome’s Longitudinal Integrated Curriculum, which allows students to follow patients throughout all aspects of their care, and the AU/UGA Medical Partnership’s small group learning model.

More broadly, Miller says, the medical school is working to redesign and modernize its entire curriculum by shortening the traditional four years of medical school to three — for all students.

“Redesigning our full curriculum in parallel to the 3+ Track is a good fit. That means we’ll accomplish what we need for the 3+ Track, as well as what students not on that track need.”

The redesign will allow for more efficient content delivery, earlier introduction to patients and clinical experiences and less milestone-based and more competency-based advancement — meaning students who are ready to move forward earlier aren’t held back by timing restrictions. The redesign also allows flexibility during the fourth year — some students may be on the 3+ Track, while others may use the year to complete a master’s degree in biomedical sciences, public health or even business administration. Others may use the fourth year to delve deeper into their chosen specialty, do research or even interview with more residency programs.

The common thread for every student will be three years of tuition, instead of four.

“Financial debt is a big stressor and a big reason many people aren’t going into primary care, particularly in underserved areas,” Miller says. “It’s a real barrier. Take away some of that barrier, and we think we can create a workforce.”

MCG students, for instance, graduate with an average debt of $167,408. According to the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, in May 2017, the average primary care doctor salary was around $200,000 annually, while many other specialists make upward of $300,000.

The Long View

In this year’s state budget, the Georgia Legislature included a recurring $500,000 to allow MCG to continue mapping out the 3+ Track. Part of that planning includes figuring out how to place more students into Georgia residency programs when there is already a shortage of slots.

Nationally, there’s a shortage of residency positions. For example, in the 2019 Match, 44,603 applicants applied for 35,185 positions. Georgia is even worse.

The national average is 34 residency positions per 100,000 population while Georgia only has about 21 residency positions per 100,000, according to a recent report by the Georgia Department of Audits and Accounts.

Part of the answer, Miller says, is filling MCG and AU Health primary care residency programs with homegrown students first. “Of the five programs (family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics/gynecology and general surgery) we have 55 first-year residency slots,” he says. “In the 2019 Match, seven MCG students went to those slots. We need to significantly increase that number. At the end of the day, everyone we’ve talked to in the departments wants to put more MCG students in their residencies. I think filling 60-70 percent of those slots with MCG students would be a good start.”

Part of the strategy for graduate medical education also includes taking advantage of new residency programs across the state that were created by the work of the GME Regents Evaluation and Assessment Team, or GREAT, Committee. That team, established 10 years ago by former Gov. Nathan Deal, the Georgia General Assembly and the University System of Georgia, had a goal of creating 400 new residency slots across the state. If all projected programs open their planned residencies, the state will have added 581 new slots by 2025. “That is a more powerful way to get people into com-munities outside of Augusta,” Miller says.

MCG’s statewide presence will also be an asset as medical school officials look to add even more GME opportunities in cooperation with community hospitals and federally qualified health centers in underserved areas of the state, for example.

“Our goal, as it is with our students, is to get residents into community settings, smaller-practice venues and more community hospitals and get them exposed to that level and model of care,” Miller says. “I think if they’ve experienced being a general internist in a community like Albany, where there’s a need and they’ve gotten to like it, that would dissuade them from wanting to leave.”

According to Umbach’s research, that’s true. MCG’s class is 95 percent Georgia residents and about 40 percent of those who graduate from MCG remain in the state to practice. They project that would jump to 80 percent for those who complete the 3+ Track.

For every MCG graduate who practices in an underserved area in Georgia, their total value to the state equals $7.2 million annually, according to Umbach.

“The physician shortage in rural areas is a huge issue, one that’s only going to worsen over time,” Hess says. “Programs like this are essential to ensuring the healthiest future for every part of our state.”

It’s a big investment for the state, but one that will see significant returns on investment, Hess says.

The Association of American Medical Colleges has released its latest report on physician supply and demand. Some key points –

- The projected shortage of between 46,900 and 121,900 physicians by 2032 includes both primary care (between 21,100 and 55,200) and specialty care (between 24,800 and 65,800)

- The United States would need an additional 95,900 doctors immediately if health care use patterns were equalized across race, insurance coverage and geographic location. This shortage would be in addition to the number of providers necessary to meet demand in Health Professional Shortage Areas as designated by the Health Resources and Services Administration

- While rural and historically underserved areas may experience the shortages more acutely, the need for more physicians will be felt everywhere. The overall supply of physicians will need to increase more than it is currently projected to in order to meet this demand.