The fist-sized heart is one of the first organs to develop and to function. The first heartbeats can start at four weeks of gestation; and the heart should be fully formed by week seven.

Congenital heart defects occur in those first few critical days and weeks.

There are known causes like thalidomide, a cancer drug that was also used as a sedative during pregnancy and can cause numerous malformations of a fetus, and the viral disease rubella, but mostly the cause is not certain.

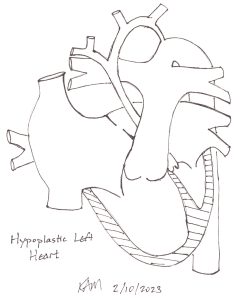

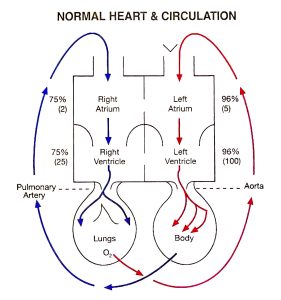

There are more than 250 different kinds of heart disease in children. One of the most serious is when the left ventricle, the pumping chamber of the heart, the mitral valves that keep blood flowing the right way and the aorta that should direct oxygen rich blood out to the body, don’t get as big and strong as they should. It’s called hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

These types of structural defects of the heart, which sustains the body with blood, oxygen and nutrition, are the most common birth defect, affecting about 1% of births per year in the United States, or some 40,000 babies, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They also are the leading cause of infant death from birth defects.

About 1 in 4 of those babies will need surgery or some other intervention in their first year of life.

Cardiac catheterization to diagnose these often-complex structural problems began to be performed routinely on children in the late 1950s. By the mid-1960s this approach was also being used therapeutically, like to palliate transposition of the great arteries where, like the name implies, the flow of the oxygen-rich blood and oxygen-poor blood is reversed. The earliest of these physicians were largely pediatricians who wanted to help and basically taught themselves. Pediatric cardiology became the American Board of Pediatrics’ first subspecialty certification in 1961.

In those early days, it was adult heart surgeons who developed an interest in the very different heart disease of children and took the lead in trying to surgically repair the imperfections. The first successful intracardiac repair reported was sealing the hole between the upper chambers of the heart, called an atrial septal defect, in 1949.

Recognizing the unique complexity of congenital heart surgery, the American Board of Thoracic Surgery finally established a subspecialty certificate in congenital heart surgery in 2009. In 2020, the Cleveland Clinic’s fellowship program became the 12th and the last approved by the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education.

A Strong start

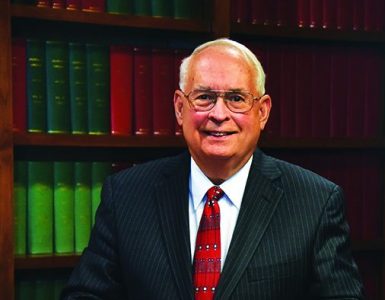

William B. Strong, MD, longtime chief of the Section of Pediatric Cardiology at the Medical College of Georgia, was the 280th physician in the nation to become board certified in pediatric cardiology and would later chair that subspecialty board.

He joined the MCG faculty in 1969, a year after MCG and its health system became a relatively early player in the formal education of pediatric cardiologists. Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, for example, which has one of the oldest and largest of these pediatric cardiology fellowships, got its start in 1965.

Strong had just completed his fellowship at Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital in Cleveland when he joined Gordon M. Folger Jr., MD, (who just passed in January 2022 at the age of 92) at MCG. Folger had helped establish MCG’s pediatric cardiology fellowship and was publishing about the medical school’s clinical experiences with children who had problems like cyanotic heart disease and tetralogy of Fallot, a combination of defects that result in oxygen-poor blood being pumped out to the body and consequently babies having a bluish tint to their skin. Folger was a great colleague, but Strong shortly found himself alone and he says, by default, a very young section chief before the age of 40.

But Strong, who exudes smarts and smiles but does not suffer fools, was undaunted. He began a series of great recruits most of whom would go on to lead other programs. His first recruit was interventional pediatric cardiologist Syam Rao, MD, who would later lead programs at the King Saud Hospital in Riyad, Saudi Arabia and at the University of Texas at Houston. Another, Linda Leatherbury, MD, a 1978 MCG graduate who trained at Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C., is back there on faculty now and is distinguished for her scientific studies in the origins of heart defects that had their roots while she was on the MCG faculty.

H. Victor Moore, MD, a 1963 graduate of Wake Forest School of Medicine who completed his surgical training at New York Presbyterian Hospital, joined the MCG faculty in 1973 as the medical school’s first designated congenital heart surgeon. Strong laughs that until the last of their some 30 years together at MCG and Children’s Hospital of Georgia, Moore referred to Strong as “Dr. Strong.”

Strong also recalls his longtime colleague, who remains his neighbor in West Augusta, as dedicated and principled, a breed of surgeon and individual who would send a child elsewhere for some rare surgery if he thought it best for that child and who could sometimes be found in the NICU in the wee hours rocking one of his tiny patients.

“Victor was unbelievably dedicated and essentially on call 24-7 for 30 years,” Strong says. “He was core to the early development and the strength of our children’s heart program. His surgical skills and postoperative management of children were excellent,” his longtime partner says.

They were a good fit, each, no doubt, exacting individuals, and no pushovers when it came to children or much else.

And there were others. It was 1985, when Strong and his longtime friend, the late educator Maury Levy, EdD, founded the Georgia Prevention Institute, one of the nation’s first initiatives focused on better understanding how children became adults with heart disease and how best to intervene. The GPI would yield pioneers in studies of salt-sensitive hypertension, the effects of stress on the cardiovascular system and the ill effects of obesity and inactivity. They were pioneers as well in building relationships with parents and the school system in Richmond County that have enabled longitudinal studies following hundreds of children with a family history of hypertension as they became adults.

And there were others. It was 1985, when Strong and his longtime friend, the late educator Maury Levy, EdD, founded the Georgia Prevention Institute, one of the nation’s first initiatives focused on better understanding how children became adults with heart disease and how best to intervene. The GPI would yield pioneers in studies of salt-sensitive hypertension, the effects of stress on the cardiovascular system and the ill effects of obesity and inactivity. They were pioneers as well in building relationships with parents and the school system in Richmond County that have enabled longitudinal studies following hundreds of children with a family history of hypertension as they became adults.

“The GPI was founded on the basis that adult cardiovascular disease and most chronic adult disease begin in the young,” Strong says.

Strong knew firsthand what it was like to lose someone too early to acquired heart disease. His father Ben had his first heart attack at age 36 and died of heart disease at 52. Ben Strong was active and strong but was also a smoker, the son says of the man who solidified his focus on the heart.

His “Gram Haslem” was sweet, colorful inspiration as well. When he was just a boy and wanted to come home after school and listen to Western star Tom Mix’s long-running popular radio show, his grandmother was no pushover either. “If you don’t get outside and play you are going to become … (well, not healthy),” she would tell him. So Strong, who in his 80s looks pretty much like he always has, would head outside.

Flash forward to 2005, when Strong cochaired a 13-member national panel convened on behalf of the CDC’s Divisions of Nutrition and Physical Activity and Adolescent and School Health that found pretty much what Gram Haslem told him: That school-age children should participate in 60 minutes or more of moderate to vigorous physical activity daily. Today record levels of obesity and problems like hypertension even in the very young, leave this pioneer still feeling a sense of tremendous frustration on this important front for children.

Cohesive care

Flash back to 1989. A few years after getting the Georgia Prevention Institute rolling, Strong was thinking that in the clinical setting the entire team of talented caregivers for children with heart disease needed a more united front.

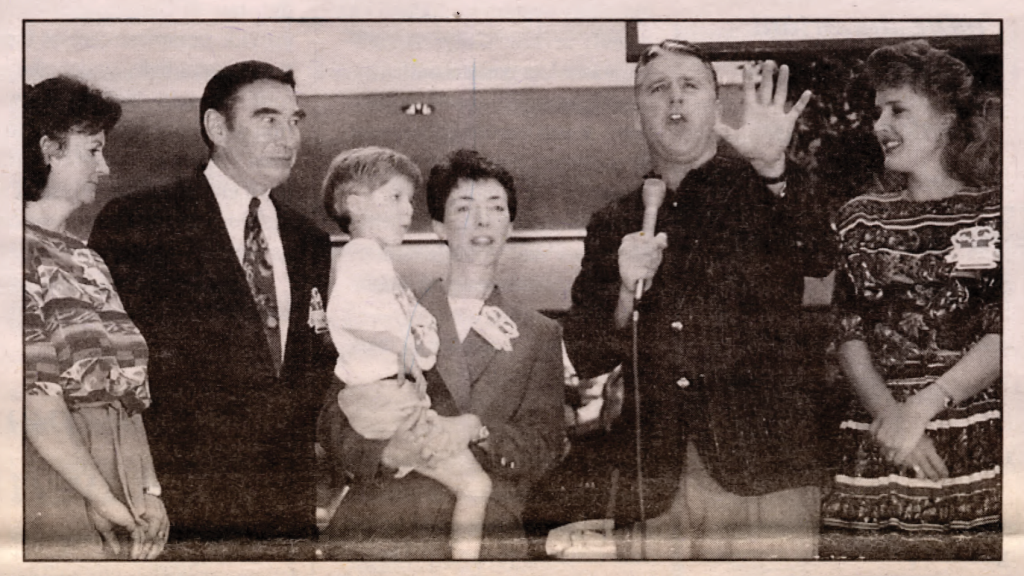

The Children’s Heart Program came together for the first time in September of that year with members of the pediatric cardiology and pediatric cardiovascular surgery teams as well as pediatric cardiac anesthesiology, pediatric critical care, neonatology, general pediatrics, nursing service, senior hospital administration and a mom to represent patients, Julie Moretz, who would later help the Health System develop one of the nation’s first programs in patient- and family-centered care and is now the health system’s AVP for patient and family centered care.

the Health System develop one of the nation’s first programs in patient- and family-centered care and is now the health system’s AVP for patient and family centered care.

The team adopted what Strong calls an “all for one and one for all” approach that brought all providers and patients to the pediatric cardiology practice site, which remains on the sixth floor of the adult hospital. They would also work collaboratively to set priorities for how limited resources would be spent. The nurses and other staff reported directly to the physicians rather than to an offsite hospital administrator. When, despite best efforts, clinic was running behind, one of the pediatric cardiologists would step into the waiting room and explain why.

Strong would talk to his young patients about their grades and their future. Like a mentor years before, he and his colleagues would sit with a child and his parents and draw out the child’s unique heart problem on a simple diagram of the heart, sign and date it, then give a copy to them to keep forever. Strong noted that not long ago a former patient, now in his 50s, ran into him in the grocery store and pulled from his wallet the tattered diagram he once drew for him.

With the same patient and family friendly mindset, Strong would establish some of MCG’s first satellite clinics at 14 divergent sites across Georgia from Athens to Savannah to Macon as well as Fort Jackson in Columbia, SC. It was a pragmatic move. Because of the relative rarity of congenital heart defects, pediatric heart programs probably needed a population of 2 million to draw from. As of this year the Augusta Metropolitan Statistical Area just reached about 610,000.

Bottom line, the heart program needed patients and patients needed the heart program. Strong remembers a family from Moultrie, Georgia. Both parents came each time as well as the young patient’s sibling. The drive up from South Georgia took more than four hours, each parent lost two days of work, the family had to stay overnight and eat meals out. Strong figured it cost them about $500 out of pocket each time in those days. But if he went to them, he could save the families having to make some of these trips and he could see 20 or 25 patients from that area on the same day.

It became one of those win-wins because the communities, physicians and hospitals there benefitted as well because more of the children’s care and parent’s money stayed there. Strong, a straight shooter but ever a gentleman, met the family practitioners, obstetricians and pediatricians on their various frontlines, including dinner meetings where he would talk with them about the patients from their communities. It was a good learning experience for the medical students who often made the journey with this natural educator. No doubt those were simpler times, Strong says, where the partnerships he formed across Georgia were sealed with a handshake.

Unfortunately, the Children’s Heart Program would become fractured about a dozen years later primarily because of the Department of Surgery’s lack of support of a programmatic approach, Strong says. It was about the same time as an Early Retirement Program offered by the university resulted in an unprecedented loss of faculty and staff across MCG and the university. Both helped set the tone for some bumpy years. Eventually, the satellite clinics could not be sustained primarily because of insufficient human power. Today only the Valdosta clinic is still active.

Strong retired from his position as section chief in 2001 but volunteered to take care of adults with congenital heart disease — a group that now outnumbers children born with heart abnormalities and that a decade ago emerged as another related subspecialty open to pediatric and adult cardiologists.

“Having a 35-year-old in pediatric intensive care didn’t work out that well most of the time,” Strong says, as largely dramatic shifts in survival both short and long term emerged because of focused programs like the one at MCG and Children’s Hospital of Georgia, with greater than 97% of children expected to reach adulthood.

Soon after Strong stepped away as chief, the pediatric cardiology faculty dwindled to only Bill Lutin, MD, today an acclaimed nature photographer, who managed with the help of then-fellow George McDaniel, MD, now on the faculty of the University of Virginia Children’s in Charlottesville, and Echocardiographer Celeste Lemieux Kessler, who remains on the children’s hospital staff today. Strong credits Lutin with the program’s survival in the lean early 2000s. Henry Wiles, MD, joined Lutin in 2001 and would serve as section chief from 2003-10.

Soon after Strong stepped away as chief, the pediatric cardiology faculty dwindled to only Bill Lutin, MD, today an acclaimed nature photographer, who managed with the help of then-fellow George McDaniel, MD, now on the faculty of the University of Virginia Children’s in Charlottesville, and Echocardiographer Celeste Lemieux Kessler, who remains on the children’s hospital staff today. Strong credits Lutin with the program’s survival in the lean early 2000s. Henry Wiles, MD, joined Lutin in 2001 and would serve as section chief from 2003-10.

Moore officially retired from his post in 2000, but was rehired to continue as the primary surgeon during a series of recruits that included the initial 2003 recruitment of James D. St. Louis, MD, who had completed his pediatric and neonatal cardiac surgery fellowship at Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City, Missouri before joining the faculty of Brown University Medical Center.

Moore, who St. Louis calls a great surgeon and mentor who solidified his decision to come to MCG, worked with St. Louis in his early days here. Still, St. Louis grew frustrated with the lack of clear direction for the pediatric heart program at those moments in time. He wanted more volume of cases, more complex cases, including a program for heart transplants and medical assist devices like left ventricular assist devices that can temporarily help support a child’s ailing heart. St. Louis left for the University of Minnesota Amplatz Children’s Hospital in 2008, where he became director of The Heart Center, Pediatric Cardiac Surgery, Pediatric Cardiac Transplantation and the ECMO Program. St. Louis would become surgical director of Pediatric Cardiac Transplantation at the University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine in 2014 and director of the Congenital Cardiac Surgery Fellowship program there four years later.

A new strength

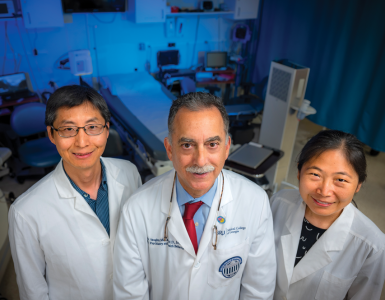

St. Louis returned to MCG and the Children’s Hospital of Georgia in 2020 as chief of the Section of Pediatric and Congenital Heart Surgery, co-director of the Pediatric and Congenital Heart Program and J. Harold Harrison MD Endowed Chair in Surgery.

He brought with him a broadened worldview of congenital heart programs and how they must change again here and elsewhere.

That same year the American Heart Association journal Circulation published a commentary about excessive mortality and complication rates in some of the nation’s children’s heart programs. It was clear something was not working in this high stakes, high reward field that today has approximately 150 centers — many within just 25 miles of each other — providing some level of this highly specialized care.

The math wasn’t working. Data collected by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons indicated centers which performed at least 300 cases annually had the lowest mortality rates while those with the highest mortality rates performed more like 100 cases.

“Sixty-five percent of the programs in this country do less than 100 cases a year, which is insufficient. That is the thing we are trying to change,” says St. Louis, who emerged as a leader in taking a national look at the problems and solutions.

As a member of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Task Force on Congenital Heart Surgery Database, St. Louis has been looking at numbers of centers, cases and survivors for at least a dozen years now. He’s also been a member of the society’s Workforce on Congenital Heart Surgery since 2016. He has been on the Executive Board of the Pediatric Cardiac Care Consortium also since 2011 and the Database Committee of the World Society for Congenital and Pediatric Heart Surgery looking at more numbers of cases and results worldwide. He’s been volunteering through the nonprofit Children’s HeartLink, in high-child density locales like China and Korea, where there are clear deficits of physicians and programs for children with heart problems.

The United States has the opposite problem.

While St. Louis and many colleagues agree that over all the care of these children in the US is superb, there are unacceptable results in some programs. For example, with the more complex defects, like hypoplastic left heart syndrome, which requires multiple surgeries to correct, having early mortality rates as high as 10-15% — compared with about 2% elsewhere, and with a major complication in at least a third of these tough cases. Many centers perform only a handful of surgeries like the Norwood operation, typically the first corrective surgery for children with this single ventricle defect. Numerous studies have associated higher volumes with the better success rates. There are also inconsistencies among centers in things like staffing, length of hospital stays and costs. Inconsistencies have also been found in lower-complexity care.

National media stories have brought the losses to life with children’s pictures and families’ sorrow. Calls began echoing for a process to help ensure the quality of the some-150 programs in the nation, most likely by reducing their number and thereby ensuring more experienced surgeons, pediatric cardiologists and all caregivers taking care of this unique subset of heart problems in children. The Circulation editorial called on the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, which sets payment standards for all insurance providers, to support a better system for these children and for professional groups to develop minimum standards for programs.

For the past two years St. Louis has worked on a Congenital Heart Surgeons’ Society committee to look at the data and produce standards for what a congenital heart program should look like, something which has not been done for 20 years in this country.

The draft is now under review by other societies relevant to congenital heart disease as well as third-party payor groups. The final report will likely recommend services any program must offer and those needed to provide high-complex care, as well as a minimum number of cases to maintain each.

A bottom line is that, maybe not tomorrow, but soon pediatric heart programs will be regulated in a sense by who payers agree to pay probably based on their numbers. “Pure numbers are probably not the way to make this happen, but it’s probably how it will happen,” says St. Louis.

And there is at least one more number concern. Despite there only being a dozen training programs for congenital heart surgeons in the country, that still translates to about 170 new surgeons out there learning at any one time, many of whom will not even find work in the surgical subspecialty they and St. Louis chose. If a surgeon does find work, they likely won’t find enough to keep them performing optimally, which ties back to too many centers doing too few cases.

It’s a bit of an odd problem to have in medicine where more typically every community, hospital and specialty is crying out for more. But it’s real.

So, much like hospitals across the nation began consolidating in earnest about a dozen years ago, in large part due to changing reimbursement trends, like a big push for more outpatient care, children’s heart programs are looking for ways to survive and thrive in a market that is out of balance.

Safety and success in numbers

Going back to those disturbing numbers, St. Louis had been searching for a good partner institution for the heart program in Augusta, where about 75-100 cases are done annually, a number that evidence indicates is not sufficient and which St. Louis says will change.

To help accomplish that, in the Fall of 2022, St. Louis signed a contract with Inova Health System, a dozen-hospital nonprofit, private health system based in northern Virginia that includes Inova L.J. Murphy Children’s Hospital. Inova, which has a 30-year history with complex heart care, was no longer satisfied with their outcomes. They shut the program down while considering what next and decided to commit the significant resources needed to make their program excel again. They had recruited Mitchell Cohen, MD, from Phoenix Children’s Hospital in 2017 as chief of pediatric cardiology and co-director of the pediatric heart program. In 2022 Inova recruited St. Louis as chief of Pediatric and Congenital Heart Surgery and heart program co-director, to take the lead in revamping and eventually expanding their program to include the most complex cases, and to start heart transplant and medical assist device programs.

While Inova has committed not to start another training program for heart surgeons, they will start a pediatric cardiology fellowship program to help ensure a healthy ratio in the nation where about 20 cardiologists are needed for one surgeon. Again oddly, there are currently not enough pediatric cardiologists to help take care of patients who need surgery as well as the majority who do not.

This time St. Louis will also remain at MCG and CHOG and direct both pediatric heart surgery programs. While many details are still in the works, his plan is to have the two children’s hospitals, which are an hour and 10-minute plane ride apart, develop a larger joint program that collaboratively will offer a full spectrum of care and have the number of cases needed to help ensure excellence.

Right after Christmas 2022, AU Health System and Wellstar Health System announced a letter of intent to move forward with plans for the Georgia-based nonprofit to assume management of the AU Health System, which includes the Children’s Hospital of Georgia. Obviously, just how plans for a joint program between Children’s Hospital of Georgia and Inova could work depends on finalizing the Health System partnership, something which should happen in the next few months, he says. But certainly, the proposed partnership with Wellstar bodes well for a more progressive health system in Augusta, including pediatric care, St. Louis says. “I think the announcement that Wellstar is moving forward has changed everybody here,” he says.

Joint pediatric heart programs are not unprecedented. “The first time Jim walked into my office, he said we have to partner with somebody,” says Valera Hudson, MD, a pediatric pulmonologist and 1985 MCG graduate who chairs her alma mater’s Department of Pediatrics and is pediatrician-in-chief of the Children’s Hospital of Georgia. The two meet regularly now and both are excited about what has already unfolded.

“It’s happening all across the country,” adds Kenneth A. Murdison, MD, chief of the MCG Division of Pediatric Cardiology, who believes the relationship is a sound opportunity for the MCG program to grow its patient numbers and ensure children with a range of care needs keep coming. It’s also a way to ensure that medical students and residents at MCG and the children’s hospital continue to get experience taking care of this unique subset of children.

Murdison notes that MCG and its health system are a bit of a rarity when it comes to these children, because the Children’s Hospital of Georgia backs directly up to the adult Augusta University Medical Center. “There is no other place in the state where I can prenatally diagnose a baby with congenital heart disease, have the baby born here and be in the NICU in 10 minutes,” Murdison says of problems which are increasingly diagnosed before birth, with good prenatal care.

An hour and 10 minutes by air

St. Louis started making the plane ride every other week to Falls Church, Virginia in September. He recruited a second surgeon, Bryan Bateson, DO, a graduate of New York College of Osteopathic Medicine who completed his general surgery residency at MCG and AU Health and Congenital Cardiac Surgery Fellowship at Seattle Children’s Hospital, to the MCG faculty in August 2022. At MCG, Bateson is also codirector of the Adult Congenital Heart Program along with Khyati Pandya, MBBS, director of Congenital Electrophysiology. Another pediatric heart surgeon likely will be recruited to MCG and Children’s Hospital of Georgia sometime in 2023, St. Louis says. His plan is to have three surgeons based at Inova and two in Augusta while he continues to operate at both places. He also plans to encourage the other surgeons to do some back and forth as well as the relationship develops.

In pediatric cardiology, Wiles, the senior pediatric cardiologist, is scheduled for a May retirement and the division is currently recruiting two more faculty to join the five who remain with his departure, says Murdison. John Plowden, MD, pediatric cardiologist and 1984 MCG graduate, is traveling Georgia to reestablish pediatric heart clinics that will again bring more care directly to patients. The physicians today say MCG’s current academic footprint, which has students living and learning all over Georgia, provides logical places to add the specialized clinical resources.

Likeminded Hudson, is moving toward ensuring the heart team has adequate ICU beds and is recruiting at least two more pediatric intensivists. “As this program builds in volume, the critical care docs will have additional training and expertise specific to caring for cardiac patients,” Hudson says.

The children’s hospital currently has 14 ICU beds and a six-bed Intermediate Care Unit and plans to add an additional 8 ICU beds. The longer-range plan is for a dedicated cardiovascular ICU in a new tower proposed as part of a major expansion for the children’s hospital. St. Louis says a dedicated ICU for these patients is today’s standard, and essential to program growth in size and scope.

Full circle

St. Louis was a 16-year-old volunteer in a hospital in Methuen, Massachusetts who quickly got promoted to emergency room orderly. He was working the night shift when a patient with a rupturing triple A, an abdominal aortic aneurysm, arrived. He was quickly promoted again, this time to holding the retractor during surgery. The sturdy football player remembers asking if he was looking at the heart and the surgeon assured him they were in the belly repairing a tear in the body’s biggest blood vessel. St. Louis wanted to be a surgeon from that day.

Working with Richard A. Hopkins, MD, then chief of pediatric cardiac surgery, while he was in medical school at Georgetown University convinced him that he wanted to a pediatric heart surgeon.

While mortality rates were high then, the ability to dismantle and reconfigure a child’s misshapen heart was quite a motivator. Flash forward 30 years and find him now working to do the same for children’s heart programs.

The Norwood

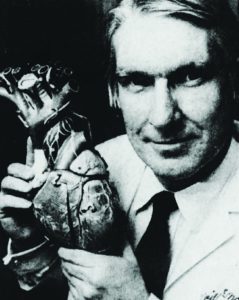

Kenneth A. Murdison, MD, was named chief of the Division of Pediatric Cardiology, in 2021. The native of Glasgow, Scotland who grew up in Canada, went to medical school at Queen’s University at Kingston and did his pediatric residency at Children’s Hospital of Western Ontario. He came south for his pediatric cardiology fellowship to the large program at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. There he unexpectedly found himself in the presence of William “Bill” Norwood Jr., MD, PhD, the surgeon who developed the first procedure to help correct hypoplastic left heart syndrome, which is fatal at birth without intervention. “He was a terrific surgeon. He changed everything,” says Murdison.

Like many pioneers, Murdison remembers this brilliant surgeon being a flashpoint for many in the pediatric heart field because they thought he was offering hope to parents for a hopeless situation. The procedure that became known as the Norwood would permanently reroute some of the blood flow within the heart to make the right ventricle, which normally pumps blood to the lungs to pick up oxygen, able to pump blood directly to the body, typically the job of the left ventricle.

Murdison and Norwood crossed paths again at Nemours Cardiac Center at Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children (now Nemours Children’s Health) in Wilmington, Delaware, where Murdison was named codirector of the Echocardiography Lab in 1998 and later medical director of the Inpatient Unit. Murdison was first author on a 1990 paper in the journal Circulation that would take a retrospective look at the famous Norwood procedure in 200 patients. What they found was that many children dwindled and died between the Norwood procedure and what was then the next step, the Fontan, where the surgeon does additional rerouting so the lone ventricle can work more efficiently by only pumping oxygen-rich blood to the body as the missing or undersized left ventricle was intended to do. Basically, the Norwood was putting too much pressure on the heart for too long with the time between the two procedures.

Norwood and pediatric heart surgery colleagues like Moore already had been thinking about how to make things work better. The evidence helped prompt the famous surgeon to also develop a go-between: the bidirectional Glenn procedure, which sent blood from the upper body directly to the lungs to take some of the pressure off the right ventricle. He also lent his name to the landmark paper.

“It gave a gradual transition between stage one and the Fontan physiology,” Murdison says. “It wasn’t such a shock and more kids started to survive.”

Norwood passed in 2020.