Study Assesses Ecological Impact of Thwarting Mother Nature

RIVERS PREDATE human beings by 10 million years or so, but that hasn’t stopped people from doing everything in their power to try to bend those bodies of water to their will.

Countless hours have been expended trying to straighten them, reroute them, dam them, tame them, and otherwise shape them to human specifications. Often, those efforts are costlier than anticipated – particularly to future generations.

Cutting to the Chase

DR. JESSICA M. REICHMUTH, Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences at Georgia Regents University, has spent several months trying to quantify the cost to one river in particular – or at least one portion of it.

[su_pullquote]River! that in silence windest Through the meadows, bright and free Till at length thy rest thou findest In the bosom of the sea! –Henry Wadsworth Longfellow[/su_pullquote]Reichmuth and her colleagues have received funding from GRU’s Small Grants Program and Center for Undergraduate Research and Scholarship Summer Scholar Program – and is seeking additional funding from the Georgia Department of Natural Resources Coastal Incentive Grant Program and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Sea Grant – to assess the Noyes Cut on the Satilla River Estuary.

“We’re trying to holistically assess the impacted tidal creeks and reference creeks in the estuary around Waverly, Georgia (about 90 miles south of Savannah),” says Reichmuth.

A cut is an embankment wall to straighten creeks and ideally prevent standing water. Extensive channels have been cut into southeastern tidal marshes to improve navigation, log transport, and access to a main river channel, Reichmuth explains. “The Satilla River Estuary has been no stranger to these anthropogenic modifications; over the past 100- plus years, eight cuts have been made in this system.”

The Noyes Cut was made in the 1930s to help timber manufacturers move trees on barges from pine uplands through the marsh of the estuary to the Satilla’s main channel. But however economically expedient the cut may have been some 80 years ago, Reichmuth says, the costs now far outweigh the benefits.

“The cut is not maintained and, to our knowledge, does not retain any of its past commercial value,” she says, noting that the pulp mill is long since obsolete. “Its main use today is to reduce travel time to the main channel of the Satilla River by a few local fishermen.”

Top-Down, Bottom-Up

IN SPRING 2013, Reichmuth, who joined the faculty after earning her PhD from Rutgers University, took a group of students to a meeting of the Southeastern Estuarine Research Society. The nonprofit group informally exchanges interdisciplinary information related to estuaries of the southeastern United States. It was there that residents of a section of Waverly called Dover Bluff made a request to help landowners dealing with challenges related to the cut.

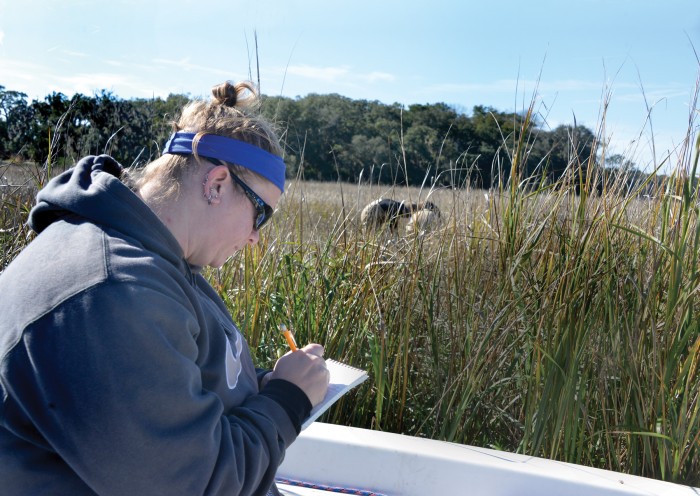

Reichmuth and the students enthusiastically took on the project of quantifying the ecological impact of the cut, a project that has involved several trips to the estuary to take water samples, assess the wildlife, and otherwise determine the costs to the environment. “We’re examining both topdown and bottom-up processes in the context of vertebrate and invertebrate ecology, phytoplankton abundance, plant community diversity, soil microbiology, crustacean genetic diversity, and water chemistry,” Reichmuth says.

Initial observations have included unusually tall marsh grass and reduced diversity of salt marsh plants in addition to a heavy accumulation of fine sediment and reduced numbers of oyster reefs in the estuary’s creeks. “The results will likely be used by state and federal agencies in the consideration of closing and restoring Noyes Cut, a project that has already been authorized and funded pending a nonfederal match,” Reichmuth says.

Faculty at Georgia Southern University are also participating, along with several of Reichmuth’s fellow faculty: Dr. Amy Abdulovic-Cui, who is using molecular

genetics to investigate crustacean population genetics and trophic level interactions; Dr. Chris Bates, who is using molecular techniques to investigate soil microbial diversity; Dr. Stacy Bennetts, who is studying the plant community composition, plant growth rate, and plant density; and Dr. Bruce Saul, who is researching fish assemblage diversity and the average size of fish populations. GRU undergraduate students, pursuing majors in fields including biology, ecology, and cell and molecular biology, are participating as well.

Eyeballing the Damage

FOR ALL the researchers’ high-tech capabilities to do things like measure the salinity of the water, Reichmuth says that anyone with a glancing familiarity of the area can eyeball the estuary and note the damage.

“Umbrella Creek [the creek outside the Waverly residents’ property] land used to be up to 300 feet wide, and today, the residents estimate it is 50 feet wide. In 60 years or so, there has been a huge reduction in creek width due to sedimentation being shuttled to this creek through this cut,” Reichmuth says. “Sedimentation can change the width and depth of a tidal channel. That’s important for migrating species like striped bass, American eels, and white shrimp. If those change, they might go up the wrong creek and think they’re farther up the river, then they might not successfully spawn, which reduces their numbers.”

Reichmuth noted that one of her students is a resident of nearby Darien, Georgia and has firsthand insight into the problem. “Her dad is a fisherman, and she understands the implications: good water quality means good levels of dissolved oxygen, the right salinity to support a healthy system,” she says. “For her, it hits home.”

The water quality also exemplifies the ripple effect of nature: Changes in the water affect the vegetation, which affects the lower life forms, which affect the species that feed on the lower life forms . . . etc., etc. Of course, the last link in the chain is the species that caused the problem in the first place: man.

Links to Human Health

“WE’RE definitely seeing water quality issues, and we’re noting changes in fish migration patterns,” Reichmuth says. “Six months [the length of the study] is such a short time, but we could be finding links to human health. If you can make the justification that protecting the environment is just as important to future generations as the economy, I think you can win out in both areas,” Reichmuth says, noting the irony that the environmental problems have long outlived the

economic benefits.

She stresses that the residents haven’t taken the problem lying down. “Some of the local landowners have come up with some ingenious ideas, including filling the area with old Christmas trees to block the cut,” she says.

Reichmuth hopes her study data will help pull in badly needed reinforcements. Once the study is complete, she will share the data with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, and the local government, which will determine next steps.

Endless Learning Opportunities

SHE IS gratified that the study is not only advancing ecological improvements, but jumpstarting undergraduates’ research opportunities as well. Says

Adrienne Kambouris, who is majoring in cell and molecular biology and forensic chemistry at GRU, “Being able to work directly with the Dover Bluff community, being able to see how their lives have been affected by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, is an invaluable societal experience. The people of Dover Bluff are humble and kind, and it’s gratifying to know that the research we are conducting will help them in the future.”

Adds Kambouris, “The scientific aspect is also fascinating. The changes to the Satilla River can be seen from the molecular to the community level. The students benefit from seeing principles discussed in the classroom happen before their eyes. Research gives the opportunity to learn collection and analysis techniques that we wouldn’t ordinarily be exposed to in a lab. I believe it is something all students should have the opportunity to experience.”

Her classmate, Jessica Bowles, concurs. “I’m learning a lot about how to take proper samples in the field and how to use special lab equipment once we get the samples back to campus,” she says.

Bowles, who will graduate in 2016, realizes how] fortunate she is to be participating so extensively in research as an undergraduate. “I am very excited to have this opportunity,” she says. “I work with a wonderful team, and I get to do my field work in a beautiful environment where there are endless opportunities for learning.”