Any event planner will tell you that coordinating a successful event is all about the numbers.

How many people can a particular venue hold? What kind of incentives should you provide? How many parking spaces, press releases and paid promotions will it take to make sure everything runs smoothly?

Finding answers to these questions and more can make hosting even a small event a nerve-racking experience.

But imagine hosting an event for nearly 500 people, outdoors, in the middle of July, at a commercial nursery where Spanish is the common tongue. Where half of the attendees are farmworkers and day laborers, and the other half are doctors and researchers working alongside students, nurses and volunteers to provide free health screenings and conduct community health research.

If it sounds overwhelming, that’s because it is. But that hasn’t stopped Augusta University and community partner Costa Farms from hosting the Costa Layman Health Fair, a comprehensive worksite health fair and research opportunity, for more than a decade.

Why?

Because over the course of the last 10 years, the health fair’s coordinators have learned that while hosting a successful event might be all about the numbers, hosting one with the power to change lives is all about the people.

From chaos, clarity

Since its inception in 2005, the Costa Layman Health Fair has served two major functions for both the university and the farmworker community.

In addition to providing meaningful outreach training for students from the College of Nursing, the College of Allied Health Sciences and The Dental College of Georgia through the Costa Layman Community Outreach Program, the fair has also helped to engage Costa Layman employees, many of whom are Hispanic farmworkers, in health care awareness, health promotion and disease prevention.

Both fronts have proven tremendously successful.

But it’s the newest opportunity – interdisciplinary research – that has the university’s health sciences educators most excited.

Dr. Andrew Mazzoli, director of the university’s Respiratory Therapy Program, has been involved with the Costa Layman Health Fair since 2009. Together with Debbie Layman, a College of Nursing alumna and former Costa manager, and Dr. Pam Cromer, associate professor of biobehavioral nursing, he was one of the first to propose adding a research component.

The first step was getting approval from the Institutional Review Board.

“This is real-people research in the environment where they’re working,” Mazzoli said. “That’s such an unusual model that when we first went to the IRB, we sort of had to convince them that, yes, we were going to have some sense of controlling the data and being true to the questions we were asking.”

Cromer said overcoming the language barrier was a primary concern.

“The bilingual issues of some of the Hispanic farmworkers was the biggest issue with the IRB,” she said. “We had to take special steps to insure these workers understood the informed consent required documents to be translated into Spanish and use certified interpreters and translators during all phases of the project.”

The second, and by far the hardest, obstacle was bringing the research to the farm – an environment Mazzoli described as a sort of “controlled chaos.”

“There are a lot of distractions out here,” he said.

Set up under the corrugated steel roof of an open-air loading platform, said distractions are easy enough to find. But location isn’t the only limiting factor.

“Worksite productivity is stressed, and certain crews with time-sensitive irrigation responsibilities feel pressured to get back to work,” Cromer said. “In order to capture the most numbers, scheduling that crew requires all booths to open at 7 a.m. to accommodate them and get them back into the fields before the sun gets too hot for watering.”

Despite the chaos, fair attendees come away with newfound clarity about their health and well-being.

Mazzoli and a team of students from the Respiratory Therapy Program spent the morning performing pulmonary function tests and obstructive sleep apnea screenings. Of the farmworkers they tested, more than 15 percent were referred for further evaluation.

The figure represents a huge impact on patient quality of life. That, according to Mazzoli, is something that can’t be measured.

“These folks are in an environment where there’s a lot of stuff to be breathed in,” he said. “When we pull up folks who maybe have obstructive sleep apnea or who have a pulmonary function disorder, they wouldn’t have found that out any other way.”

From darkness, opportunity

From darkness, opportunity

While crucial to understanding the health needs of the farmworkers as a whole, the information Mazzoli and his team collected represents only a fraction of the data gathered.

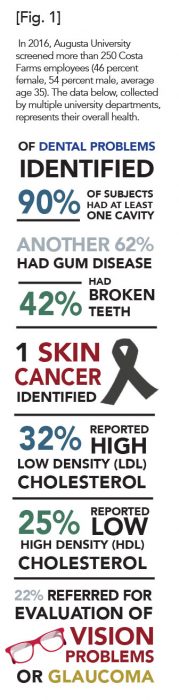

In addition to respiratory health screenings, teams from the College of Nursing, the College of Allied Health Sciences and The Dental College of Georgia provided a number of free examinations, including dental screenings, HIV testing, heel bone density, carpal tunnel and dermatological screenings as well as various tests for visual impairment.

Cromer and her team, comprised of Clinical Nurse Leader students and College of Nursing alumni, spent the morning collecting data on various cardiometabolic risk factors.

“Heart disease is our top priority in any population,” Cromer said. “And so, we want to study any of the potential effects the environment might have on patients we assume to be at risk for heart disease.”

Over the years, Cromer and her team have gathered data from hundreds of patients as part of the ongoing Cardiometabolic Risks of Hispanic Farmworkers in Southeast Georgia (CHARM) study. Led by Dr. Yanbin Dong, associate director of the Georgia Prevention Institute, the study serves a threefold purpose: to characterize long-term progression of cardiac and other metabolic risks, investigate for possible influences related to health risks and establish a biorepository for future studies with university-wide multidisciplinary collaboration.

The information collected is troubling at best.

Following the 2016 health fair, Cromer and her team found that vitamin D deficiency was the number one cardiometabolic risk factor among farmworkers (73 percent prevalence) with more than 85 percent of female workers testing positive for either vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency. The second biggest risk was obesity (71 percent), followed closely by hypertension (54 percent) and diabetes/prediabetes symptoms (53 percent).

The numbers show a population in desperate need of medical intervention. Combined with other teams’ findings, the data paints an even darker picture. (Fig. 1)

But Cromer doesn’t see it that way.

Instead, she said, she and her team see opportunities in the figures. Opportunities to improve health care and health awareness for an at-risk population and opportunities to foster even more collaboration in the future.

“We feel like everybody has a specialty, and if we can work together and learn from each other and use that skillset and that knowledge, then ultimately, the patient benefits,” Cromer said.

From understanding, love

While other physicians worked the fair in lab coats and scrubs, Dr. Jose Vazquez and his team at the HIV screening booth wore jeans and T-shirts.

Together, they spent the morning manning the Augusta University Ryan White Program’s mobile HIV testing unit, providing free, confidential testing in the comfort of an air-conditioned mobile clinic.

The casual dress was a conscious decision. Not because of the heat – a humid 91 degrees – but because of the community.

“The biggest concern with this population is that they wait until they’re very, very sick to come to the doctor,” Vazquez said. “Other populations we see – at the slightest drop of a hat, they’ll come in to be seen.”

Part of that discrepancy stems from a distrust of Western medicine. A 2012 Census Bureau report discovered that 72 percent of Hispanics refused to take prescription drugs. Another survey administered in Colorado in 2013 found that 45 percent preferred home remedies to formal care. Factors like communication barriers, lack of insurance, and pride also play into the equation.

The end result, Vazquez said, is that many Hispanics – especially on the farm – receive care too late or not at all.

“These guys, once we see them and they’re infected, they’re very sick,” he said. “It’s so much easier to catch them early on when they’re asymptomatic, but it’s a struggle.”

Overcoming that struggle requires a certain level of understanding. Dressing casually and, in the process, removing the stigma of seeing “the doctor” is only one example.

Another is bringing the care to the people.

“It’s important for our students because they’ll do more pulmonary functions in one day here than they will in an entire school year in the classroom,” Mazzoli said. “But it’s important for the workers. This is where they work. We’re not having to drag them away to the university.”

The extra effort makes a difference. Despite the cameras and the commotion, it isn’t uncommon to find farmworkers grinning and trading friendly banter back and forth with their caregivers.

But the work shines through in the form of research, as well.

“Information obtained from the CHARM study lets researchers study the epidemiology and development of the farmworkers’ cardiometabolic health,” Cromer said. “Using that data, we can implement early prevention, lifestyle modification and therapeutic treatment, which will in turn lead to higher quality of life and productivity among the farmworkers’ community.”

As for why many teams show up in greater numbers year after year, Mazzoli said it stems from a lesson he and his fellow professionals try to impart to students.

“I’ve always told my students when they leave, go forth and do great things, and do small things with great love,” he said. “That’s when people get taken care of.”