“Take a soda straw and just breathe through it, and that is what it’s like,” says Dr. Paul M. Weinberger. “It’s shocking.”

And it can be deadly.

The day Debbie Anderson really felt it, she didn’t know whether to call 911 or husband Mark. The disciplined doer was no couch potato bounding up the stairs of her Martinez, Georgia, home that day. She is a lifelong mover, playing high school basketball and softball then growing into a trim adult runner, walker, golfer, tennis player and bike rider. She is a 61-year- old with an endless, self-prescribed list of things to always do, do and do.

But that day, it felt like something was in the way of her getting a deep and meaningful breath. “It scared me,” she says, which made breathing even harder. She thought she would pass out or worse.

It wasn’t the first time she felt this, just the worst time. The first time was probably years before when she could hear her own wheezing as she uncharacteristically fell behind her friends hiking a mountain trail. She was told it was likely exercise-induced asthma — certainly it got worse when she regularly pushed herself. Anderson wanted the inhaler to help her, but it didn’t really. Instead, she got progressively worse. So that day, she collected herself and called her internist, Dr. Andrew Sanders. He sent her to Weinberger (’05), a reconstructive airway surgeon at the Medical College of Georgia.

The rare and narrow

Anderson had idiopathic subglottic stenosis, a rare, unexplained narrowing of her trachea, the short, cartilage-ringed tunnel that funnels air directly into her lungs. “We have no idea how quickly it happens,” says Weinberger. The “squeaky noises” patients start making when they breathe are commonly blamed on problems such as asthma, and patients often get shuffled to multiple physicians. Routine exams through the mouth really provide no clear clues since the trachea, which starts just above the tip of the breastbone, can’t be seen from there.

“The average ENT will probably see one of these in a lifetime. The average pulmonologist, internist and family medicine physician will never see one,” says Weinberger, who yearly will only see three or four patients like Anderson with the rarest of this rare airway disorder.

A healthy trachea is about the same length and width as putting your thumbs end to end. In patients like Anderson, scar tissue can inexplicably build inside the air passageway, narrowing it to straw size or less. As the name indicates, there are no known causes, not even smoking, but Weinberger theorizes that there is some sex-linked genetic trait because of the propensity for this idiopathic type to occur most commonly in middle-aged, otherwise healthy women.

Acquired subglottic stenosis also is more common in women, but about 40 percent of cases are in men. Known causes include long-term intubation for patients, such as adults and premature babies in intensive care, as the tube that enables their breathing during a period of crisis ultimately results in scarring that threatens breathing again, says Dr. Gregory N. Postma, vice chairman of the MCG Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery and director of the Center for Voice and Swallowing and Airway at AU Medical Center.

Now that more patients survive severe illness, there are more with this unfortunate consequence, Postma says. In fact, when endotracheal tubes first came into common use in the early 20th century, the then-high-pressure tubes resulted in high levels of tracheal stenosis. Today, anesthesiologists tend to reach for the smallest tubes that will do the job, sometimes even opting for pediatric tubes in adults, says Dr. Steffen Meiler, chair of the MCG Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine (More on Meiler, page 38).

But even when everything is done right, scarring may result from the unnatural state of having a tube in the windpipe, agree members of this elite, high-risk airway team.

External trauma to the airway is another cause of subglottic stenosis; increasingly, so is obesity as well as the often-related esophageal reflux, as acidic stomach contents find their way into the airway where they bathe, inflame and scar the trachea. A common thread is the inflammation, a natural part of healing, which — like those airway tubes — can also do damage.

When there is quite literally not enough passageway to take a deep breath, inserting the instruments to fix the problem is itself a problem that starts with putting the patient to sleep.

“You have to work fast,” says Meiler, acknowledging that even in an academic medical center where many cases are complex, these patients are among the toughest from the all-important airway point of view.

Patients are totally supine for maximum visibility down their airway and fully paralyzed for the delicate work ahead. To negotiate the treacherous path before them, Meiler and his ENT colleagues have a common focus on airway management and a heightened sense of team as they stand at the head of the bed.

An angle with a view

Surgery starts with mask ventilation where Meiler essentially becomes the ventilation machine breathing for the patients. A super-narrowed trachea often means he must act quickly to start jet ventilation, taking high-pressure air from the wall of the operating room, down-regulating it to a safe pressure for the lungs, then shooting the oxygen past the voice box through whatever narrow passage is there. Weinberger carefully but quickly places a video-assisted laryngoscope into the patient’s mouth. The laryngoscope has an angle that improves the chances they can actually visualize the glottic opening between the vocal cords that they need to enable breathing support. Once it’s in place, Meiler methodically gives oxygen for a few seconds, stops, and the paralyzed patient spontaneously exhales as the lungs and ribcage naturally recoil. Meiler notes that this labor-intensive approach does not, like mechanical ventilation, also scrub carbon dioxide, but higher levels are well-tolerated as long as oxygen levels stay solid. Weinberger likens jet ventilation to one of those fans without blades. “If we know the anesthesiologist can breathe for the patient with the mask, the pressure drops down a lot,” he says. But not much and not for long.

Like one room isn’t stressful enough, Meiler typically moves back and forth between Weinberger’s and Postma’s rooms on Thursdays, the day all types of nonemergency airway surgeries are done at AU Medical Center. But for these patients, there are always contingencies. Multiple referrals and delays may mean the situation is dangerous by the time Weinberger or Postma sees a patient in clinic, so there also are standing orders to get those patients straight to surgery. Weinberger at least gave Anderson one day’s notice. Whatever day the airway team works, there are anesthesiology residents and laryngology fellows learning to be the next generation of airway experts.

Once they have secured access to or through the trachea, Weinberger’s treatment of choice is endoscopic dilation of the narrowed passage with an amazingly powerful balloon that can be as small as the tip of a pen. Weinberger likens this technology to what EMTs and paramedics use on the scene to pop the door off a car.

“These balloons are crazy strong,” he says. The clear, cylindrical-shaped device is quite literally strong enough to stand on so it could clearly do a lot of harm, as well as good, inside the confines of the delicate airway. In fact, his amazement and concern over their force led to a published study of computer-generated cricoid cartilages — the ring-shaped cartilage of the nearby larynx. In this study, Weinberger and his team used a 3-D printer to create over 160 cricoid cartilages and showed that fracturing was definitely a valid concern using both the flexible and more rigid versions of these balloons. But the airway team is already holding its breath at that point since just inserting the balloon occludes, at least for a few moments, whatever narrow path for oxygen the patient had left.

In this tight, delicate anatomy, there is another powerful and risky tool at use. A computer-controlled laser — similar to the technology used for the Stone Mountain, Georgia, Lasershow Spectacular — moves the burning laser light faster than a human hand could, reducing damage to nearby tissue. It enables strategic cuts that prompt the scar to cave where Weinberger wants. “It’s kind of weakening the scar tissue,” he says. The tradeoff here is that the laser, limited to use by the military and in health care, also can burn through wood or steel and certainly the airway.

Always part of Weinberger’s technique are the steroid injections that, over time, will help calm the chronic inflammation that is a common factor for even idiopathic patients like Anderson. Patients these days also routinely take home a prescription for a drug that reduces stomach-acid production.

In the best-case scenario, outpatient injections of steroids may be all a patient needs. In the most difficult scenarios, like when patients arrive at the Center for Voice and Swallowing and Airway with a tracheotomy to enable breathing, airway surgeons must open the neck then clean out the tracheal blockage. Weinberger prefers to avoid this open approach if at all possible. His lessons learned include the fact that cutting out scar tissue amplifies the scarring problem, and much as with the breathing tubes, the tracheotomy that enabled breathing likely also worsened it. While some scar tissue may return after dilation, the hope – and the reality for most of his patients – is that less comes back, leaving patients with more room to breathe.

Commonly patients may need more than one dilation. Anderson had two, and Weinberger took a third look at her in August 2014. But so far, no additional work is needed.

Postma, who has a fitness instructor and a distance biker among his airway patients, encourages all to stay active and attuned to their breathing. Stronger hearts and lungs can even enable them to breathe through a smaller windpipe and at least delay another dilation or outpatient “tune up.”

Anderson didn’t need encouragement. “In two days, I was upstairs on the treadmill, and I was running. I was so excited to be able to breathe.”

h5>

The Natural Path of Air

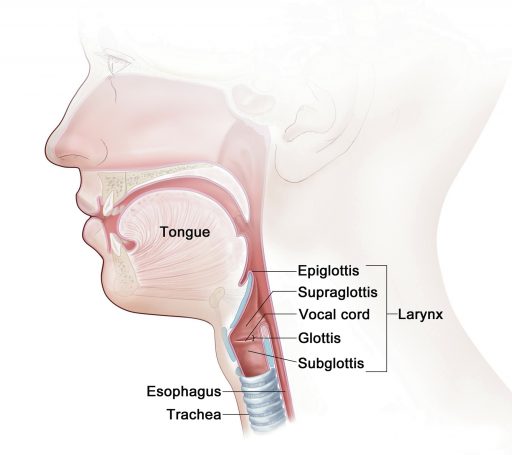

The curved path to the trachea starts with the mouth. Next is the oral pharynx, which is basically the part of the throat behind the tonsils and a connector where swallowing starts. The larnyx follows, a sorting machine that sends food and liquids down the esophagus and air into the trachea, the final connector to the lungs.

Finding the Best Practices Treatment

Alternatives in Adult Rare Diseases: Assessment of Options in Idiopathic Subglottic Stenosis, funded by a $2.3 million grant from the federal Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute and led by Drs. Alexander Gelbard and David Francis at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, is taking an international look at treatment approaches and outcomes for idiopathic subglottic stenosis. The study brings together for the first time the world’s top airway surgeons at 30 academic medical centers, including Augusta University Medical Center.

“Because it is so rare, nobody has been able to pull together enough patients to make any headway with this disease,” says Dr. Paul M. Weinberger, a principal investigator. “This is the first study to really pull people together who treat this.”

Like his comparatively small number of colleagues across the country who tackle these tough surgeries, Weinberger thinks his approach is the best or he would change it. But the head-on comparison will enable a larger, more anonymous assessment of multiple specifics – such as steroids or no, endoscopic or no, laser or no, rigid dilator or no – and the results.

While his success rate with the idiopthic cases is essentially 100 percent, there is always power in objective data review, he says.