According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, misuse and overuse of antibiotics is the leading cause of antibiotic resistance in bacteria.

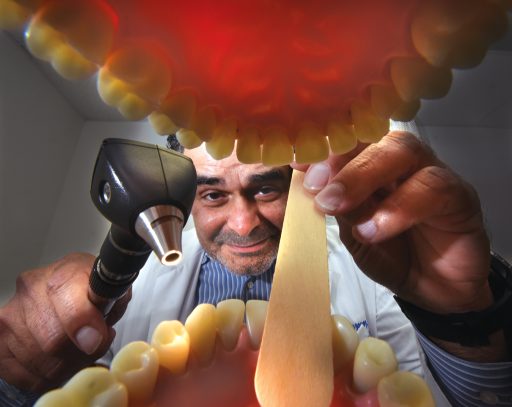

It’s an alarming find, but not a very surprising one, said Dr. Jose Vazquez, chief of the Antimicrobial Stewardship service at Augusta University Medical Center.

Vazquez, a member of the Infectious Disease Society of America, the International Society for Infectious Disease and the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases, is an expert in the field of chronic wound infections. He has witnessed firsthand the devastation so-called “superbugs” wreak on the human body. As a practicing physician, he’s also seen the role “clumsy caregiving” has played in creating antibiotic resistance.

“A friend of mine was going to her doctor recently because she thought she had strep throat,” Vazquez said. “When I questioned her, her defense was that her doctor had prescribed all these various antibiotics the last time she went in with the same symptoms.”

After hearing the list of prescriptions, Vazquez said many were inappropriate treatments for the symptoms she’d described.

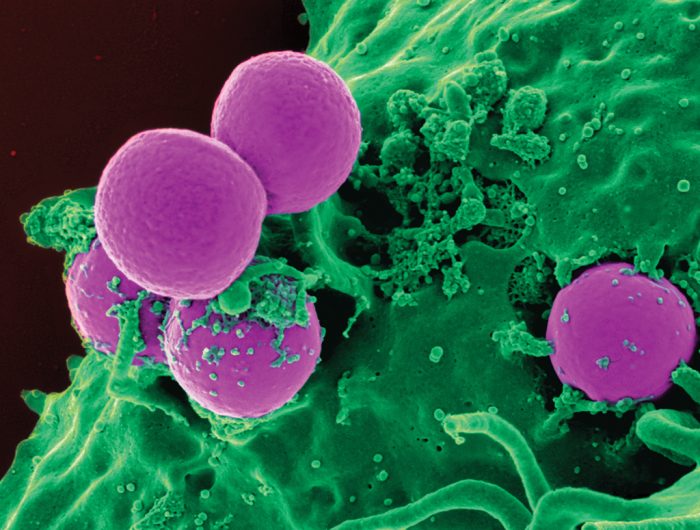

Such misdiagnoses are not only common, they’re also extremely dangerous because viruses like the ones responsible for strep throat aren’t affected by antibiotics. Instead, “good” bacteria – such as Lactobacillus, which produces lactic acid to aid digestion – take the brunt of the damage. Afterward, any single-celled organisms that survive, including potentially harmful bacteria, begin to develop genetic resistance to the antibiotic used.

“After repeated exposure, a gene in the organism’s system will mutate, causing the bacteria to develop a certain type of resistance mechanism,” Vazquez explained.

Some bacteria develop thicker cell walls to keep antibiotics out. Others filter medication from their system entirely. But the most interesting, and perhaps most disturbing, form of antibiotic resistance is a type of cell-to-cell communication known as “quorum sensing” – a process in which bacteria share genetic material to coordinate resistance activation.

Vazquez, whose research involves investigation of the epidemiology and management of mucosal candidiasis, invasive candidiasis as well as the management of systemic fungal infections, warns that, while comparatively rare, superbugs are becoming increasingly more common in the United States. Only recently, he and his team worked to treat a patient suffering from an antibiotic-resistant strain of Enterococcus – the most common cause of urinary tract infections. Though Vazquez and team were able to cure the patient, others are not so lucky.

A report commissioned by the British government found that, if left unchecked, superbugs will kill more people annually than cancer by 2050.

Better use of antibiotics and stronger infection control programs top the list of ways physicians can fight the growing superbug menace, but for the average person, Vazquez has one piece of advice.

If your doctor gives you antibiotics without telling you why, he said, “You shouldn’t be going to that doctor anymore.”