The Beauty of the 200-mile Satilla River is second to none, but Augusta University researchers believe the altering of the river’s landscape is destroying the wetland’s ecosystem.

From the enchanting Callaway Gardents to the breathtaking waterfalls in the Chattahoochee National Forest, Georgia has no shortage of stunning locations.

One of Georgia’s hidden gems is the Satilla River, which stretches over 200 miles. Numerous species of fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals call this basin home. The diversity of the river’s wildlife includes common species, but among them are endangered animals such as the indigo snake, the wood stork and the redbreast sunfish.

Although the river’s beauty is often described as being second to none, Augusta University researchers believe the altering of the river’s landscape is destroying the wetland’s ecosystems.

Plunging into crisis

Over the last 100 years, the Satilla River has been cut eight times for industry purposes. However, the most notable passage is Noyes Cut, which was originally opened in 1910 for log transport and then expanded in the 1930s by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Since its expansion, Noyes Cut has not been maintained or managed, said Augusta University biology professor Jessica Reichmuth. This has resulted in an increase of sedimentation downstream as well as changes in the water’s flow and dissolved oxygen level more than likely caused by altered tidal exchange.

“With these changes to the water column, we are now beginning to see a potential impact in the area’s estuarine community,” Reichmuth said. “Research is showing a change in distribution of resident and migrating fish species in addition to commercial species including white shrimp, American oyster and the blue crab.”

The first complaints about the river’s sedimentation levels were made in 1935 by Dover Bluff Club landowners, after which scientists began researching the property. However, Reichmuth says these past studies primarily focused on the water chemistry, noting changes in salinity, dissolved oxygen and water flow. The goal of her study is to provide a more holistic assessment of the area by combining an analysis of the water quality and chemistry as well as the biology and ecology of the river’s estuary.

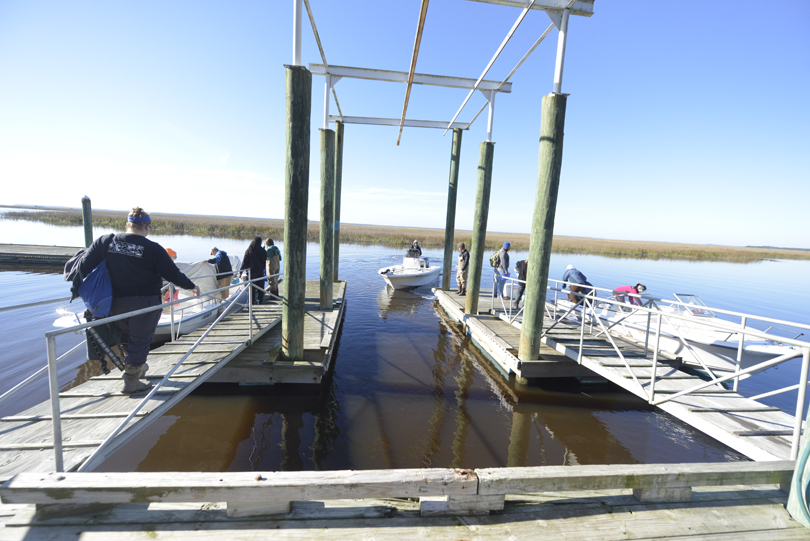

For over three years, Reichmuth and other faculty from Augusta University’s Department of Biological Sciences (in addition to faculty from Georgia Southern University) have studied the river’s estuarine systems by pulling samples from four sites, including Piney Bluff Node and Noyes Cut, to study the area’s fish assemblages, invertebrate and plant communities, soil microbiology and water chemistry.

The research team’s combined analysis of sediment metal and sediment grain size revealed the highest levels of silt and metals are found at the river’s Piney Bluff Node, which sits downstream of Noyes Cut. This area also showed a decrease in salinity and fish assemblage diversity, including the absence of long-distance migrators and diadromous fish such as American eel and

striped bass.

These changes in the river’s ecosystem support Reichmuth’s hypothesis that Noyes Cut has altered the flow in that portion of the Satilla River.

“Our data continues to show evidence that the altered landscape has impacted the wetland environment, and the accumulation of metals and silt is having a profound effect on the microbial community as well as the carbon cycling and other important biogeochemical cycles,” Reichmuth said.

Reichmuth’s research team has been working closely with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineering on this crisis, and even when the Corps concludes its modeling efforts later this year, Reichmuth’s team plans to continue assessing the interactions between the area’s structural development and the wetland’s ecosystem.

Turning of the tides

Accompanying Reichmuth’s research team on this project are students enrolled in her biology undergraduate research course, and they have volunteered nearly 2,500 hours to the study. Reichmuth says she is using this project to help them think outside of the classroom and apply what they learn in lectures to real-world problems.

Senior cellular molecular biology major Alexander Leach has been studying the Satilla River’s soil bacteria since 2015, and he hopes to present his results by the end of the year.

“I have learned so much by working on this study, and the first-hand experience has made me more conscious of what I am doing with my own work in class,” Leach said. “The opportunity of working with professionals and faculty has been an eye-opening experience, and I have considered pursuing a graduate degree in ecology and research.”

Senior ecology major Elise Thomas and senior cellular molecular biology major Keturah Mingledolph have also worked on this project for two years and share similar stories.

“Since working on this project, I have studied the genetic diversity of the river’s crabs and sampled the stomach contents of over 200 blue crabs to learn more about their diet,” Mingledolph said. “This has been such an amazing experience, and it feels good to know that our work will help to make things better for those living near the Satilla River.”

“We learn about so many organisms in zoology, and to get a chance to see them in person is mind-blowing,” Thomas said. “For the last year and a half, I have visited the river every month studying diatoms, and I plan to continue this research even after I graduate next spring.”

Oftentimes, undergraduate research is viewed as beneficial only for the students. However, Reichmuth says seeing her students participate in this study is a full-circle moment for her.

“I see myself in these students because it was undergraduate research like this that inspired my career path” Reichmuth said. “I feel like I’m passing the baton to the next generation of scientists, because when our students succeed that means we succeed.”

Many of the students who have participated in the Satilla River study have presented their results at various conferences throughout the country, and some will have their work published in peer-reviewed journals.

This study was initially funded for the first year through Augusta University’s Center for Undergraduate Research and Scholarship Summer Scholars Program in addition to the Small Grants Program. The previous two years were funded by the Georgia Department of Resources Coastal Incentive Grant Program. Reichmuth is currently applying for more funding and hopes to have a complete ecological assessment soon.