Renowned physician’s credentials questioned as she works to help fellow passenger

She was president of her first-year class at the Medical College of Georgia and is now on faculty at Harvard Medical School.

She’s earned a master’s degree in health policy and management from Emory University and a master’s of public administration from Harvard.

She’s held leadership positions in groups like the American Medical Association and the American College of Physicians, and she’s been invited to give hundreds of regional, national and international presentations on her work in obesity medicine.

But on October 30, 2018, Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford, ’07, was simply a physician trying to help a woman through a mid-flight panic attack, no matter what the flight attendants on board believed.

Just like waking up to eat breakfast

It was a Tuesday and Stanford was returning to Boston from a business trip to Indianapolis. It was just like any other day, she remembers thinking. “I travel a lot for work, so being on a plane for me, is like waking up to eat breakfast,” says the internist/pediatrician who is recognized nationally as an expert in obesity medicine. “In fact, it was going to be a short trip home. The next day I had to be in Pittsburgh to give the keynote for the American Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, and then the next day, I had to be at the American College of Physicians headquarters in Philly.“

With about 130 emails to check, Stanford had settled into seat 9B for the two-and-a-half hour flight. Just before the flight crew closed the doors to the plane, a young woman rushed on the plane and to her seat – 9A. As the plane climbed to its cruising altitude of about 30,000 feet, it encountered turbulence and began to shake. The woman next to Stanford, who had fallen asleep, suddenly jerked awake, began kicking seat 8A in front of her, pushed her seat all the way back and began to tremble and hyperventilate.

Stanford sprang into action. And that’s where the trouble began.

“I was trying to figure out what was going on with her. I didn’t know if she was having a seizure,” Stanford says. “She was so close, directly to my left, that even if I weren’t a physician, I would have been trying to figure out how to help this woman.”

A flight attendant approached Stanford and asked if she was a doctor. Stanford answered yes and produced the pocket-sized version of her medical license she keeps in her wallet. “She looked at it very quickly and walked to the back of the plane as I was still trying to figure out what was going on with this woman next to me.”

Stanford sensed that the woman was having a panic attack and as she was making sure, another flight attendant approached and asked to see her medical license again. She produced it again and then began thinking of ways to help the woman next to her relax – including switching seats to allow her more room to stretch out. As soon as the two switched seats, both flight attendants reappeared asking for more verification that Stanford was a physician.

“The first flight attendant asked, ‘Are you a head doctor?,’” she remembers. Confused at what they meant and why they were questioning her credentials while a passenger was in distress, Stanford stated she was an MD and reminded them that they had both just seen her medical license.

“That’s when the second flight attendant asked ‘Well, is that really yours?’ implying that I was carrying someone else’s license,” Stanford says. “I think that after she said that, they both realized that was over the line and they both left and walked to the back of the plane. Meanwhile, I’m still focused on this patient and I’m the only one that’s helped her at this point.”

An eerily familiar scene

The incident felt eerily familiar to Stanford. Just two weeks before, she’d had the opportunity to interview Dr. Tamika Cross, who had come to the Massachusetts Medical Society to lecture on gender and racial bias in medicine.

The incident felt eerily familiar to Stanford. Just two weeks before, she’d had the opportunity to interview Dr. Tamika Cross, who had come to the Massachusetts Medical Society to lecture on gender and racial bias in medicine.

In 2016, Cross, a young black obstetrician/gynecologist at Memorial Hermann Hospital in Texas, was flying Delta Airlines home from a friend’s wedding when a man on her flight fell ill. A call for help came over the loud speaker, but when she tried to help a flight attendant dismissed her saying “We are looking for actual physicians or nurses,” according to Cross.

She shared her story on Facebook, which resulted in thousands of comments and similar stories from minorities and women who said they had faced the same skepticism about whether they “looked like doctors.”

Her story helped trigger changes in Delta policies, too. As of Dec. 1, 2016, the airline stopped requiring medical professionals to produce his/her credentials before helping a passenger in distress. Stanford’s flight from Indianapolis back to Boston was a Delta Connection flight.

Viral

Stanford was able to successfully calm her fellow panicked passenger by talking to her and reading her emails on her laptop. As the plane began getting ready to make its final descent into Boston, one of the flight attendants returned to row 9. “She told me, ‘I just want to let you know that we don’t need to see your license again, because we think you did a good job,” she remembers.

After walking the young woman to her next flight, Stanford headed home to her husband. After she relayed what had happened to her, he encouraged her to tweet Delta about it.

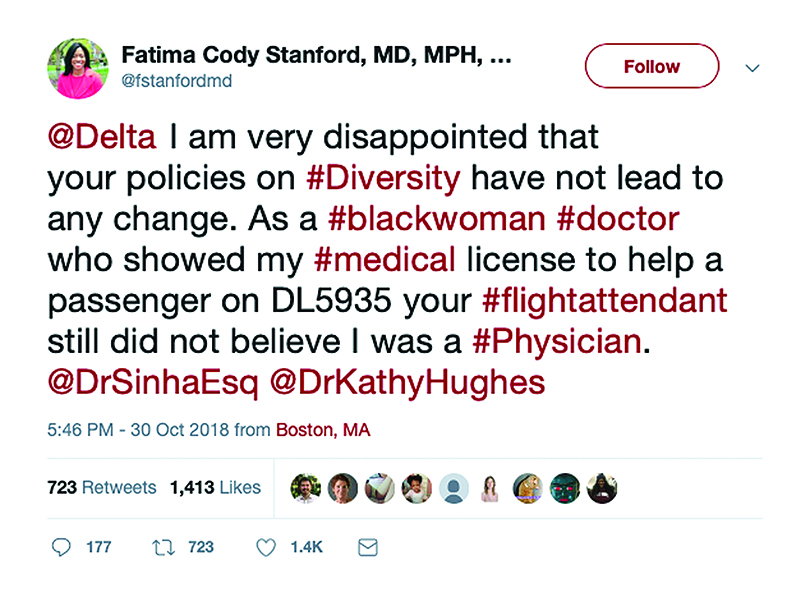

At 10:30 p.m., she wrote on Twitter: “@Delta I am very disappointed that your policies on #Diversity have not (led) to any change. As a #blackwoman #doctor who showed my #medical license to help a passenger on DL5935 your #flightattendant still did not believe I was a #Physician.”

By the next day, The Boston Globe had found her tweet. So had the Boston Fox affiliate. And then media outlets around the world did too. “My husband had predicted that this would go viral, and I was doing like 20 interviews a day,” Stanford remembers.

She didn’t publish the details of the flight on social media to seek notoriety, rather to shine a light on something that she had seen firsthand and that continues to be an issue for minority physicians – something she wants to see change.

“Yes, I think this happened because I was black. Some people think it was because I look young,” she says. “I think it was a compilation of things – first because I was black, second I was female and third was my age. I think commercial airlines need to continuously train their employees in matters like this – in explicit and implicit bias. It’s not just the airlines. It’s an issue that’s so pervasive throughout society.”

And as important as that issue is to Stanford, she also says that at the end of the day, what mattered most was that her patient was OK. “They were so focused on whether I was who I said I was, or who my license said I was, that they never stopped to ask this woman how she felt. Her being OK and feeling better was what was most important.”

Making it better for those who come behind her

That protective and proactive nature is what called her to pursue a career in medicine in the first place, she says. “When I think about the role of the physician and the care of patients, and really just how influential they are in the daily lives of their patients, that was really compelling to me at a very early age. I had a strong desire and felt a pull to (become a physician) very early – about the age of 3.”

Stanford was her high school valedictorian and attended Emory University, where she was again top of her class and earned a bachelor’s degree and a master’s in health policy and management.

After working as a prevention coordinator for the Dekalb Rape Crisis Center, Stanford came to MCG in 2003 to pursue her dream.

Her years at the state’s medical school were not all happy though.

“Unfortunately, what happened on that Delta flight was one of the less damaging experiences of my life,” she says.

A natural go-getter, Stanford ran for first-year MCG class president and won. As the first black class president, she was soon approached by the university’s historian about honoring Grandison Harris, the former slave who robbed Augusta graves to provide early MCG students with cadavers, at the medical school’s upcoming spring body donor memorial services. After bringing up the idea up to her classmates – about half of whom had strong objections about bringing up the medical school’s controversial past – something shifted, Stanford says, and things became difficult.

It wasn’t uncommon that she would have things thrown at her during class and a newsletter was circulated among her classmates that made fun of her “black traits, the size of my nose, the width of my hips and butt, the contrast of my teeth’s color to my skin color” for example. She ran for president again her second year and was defeated.

“What I experienced at MCG was harder because those were my peers, who are now physicians,” she says. “But that did help me know how to navigate situations like what happened on the plane. That experience, and my experiences in medical school made me want to find some way to make things better for those who come behind me. I’ve had physicians from all over the country tell me how they were better treated after hearing about my experience (with Delta). I hope hearing what happened to me on that plane and how I dealt with it makes it better for those that come behind me.”

Did You Know?

- Dr. Fatima Cody Stanford also earned

her master’s in public administration from

the Harvard University Kennedy School

of Government. - After an initial interest in orthopaedics,

she pursued a residency in internal

medicine/pediatrics. - Her grandmother took her to Bill Clinton’s

1993 inauguration, which she says influenced her

to become a voice in public health policy. - She worked as a health communications officer

at the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention before coming to medical school. - She completed a three-year fellowship

in obesity medicine and nutrition at

Harvard Medical School and

Massachusetts General Hospital. - Prior to the American Medical

Association’s vote to acknowledge

obesity as a disease, Stanford

served as their keynote speaker. - Her work in obesity medicine

and disparities has been

covered by news outlets such as

The New York Times, CNN,

Time, Self and Cosmopolitan.