Dr. Brian Annex

Chair

Medicine

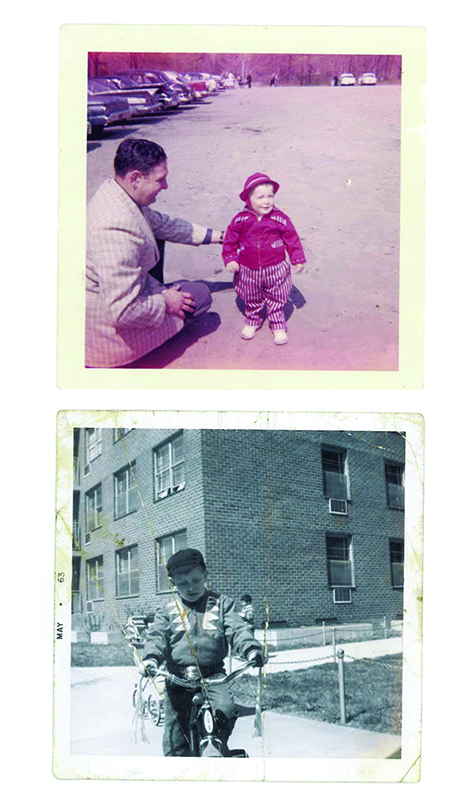

A very young Brian Annex liked figuring out how things work, why they didn’t and was drawn to the opportunities to do both in science and math.

He would grow up in one of Brooklyn’s massive, subsidized apartment buildings with father Howard, mother Sandra and younger brother Alan. He was working by age 12, delivering newspapers and making home deliveries for neighborhood pharmacies after school, because he wanted to work and liked having the spending money.

By his junior year of high school, Annex was also doing volunteer work at a New York City hospital, transporting patients, blood and generally trying to help. He liked it, and volunteered for the ambulance corps his first semester of college at the State University of New York at Stony Brook. He would become an EMT and an officer in the program.

In those first interactions with patients, he was able to balance empathy and objectivity, and find his future.

At Stony Brook, Annex would choose arguably one of the toughest majors: biochemistry. The cost of the state university made it a natural choice for him in 1977, but like other New York schools, it was also a great place to learn, for which he remains grateful.

When it was time for the next step of medical school, he applied to about a dozen programs, including Yale University School of Medicine. He reached for Yale “because there was something exciting about it.”

Annex was put on Yale’s wait list, but it happened, and he was at home the morning the call came. One of his first thoughts was that he could not afford it, but the person on the other end said the next call would be from financial aid. He ended up paying about what it would have cost him to go to a state medical school and found Yale an unbelievable place to learn.

Opportunities present

At Yale, the young man who did not categorize himself a top student became more immersed in science and medicine. While Annex grew up just five miles away from the international metropolis of New York City, it was at Yale that he first found himself surrounded by earnest brilliance from around the world. There was a definite level of expectation, but he quickly learned he could hold his own.

Although he arrived at his internship year torn between cancer and cardiology, within a month, two absolute legends were his first cardiology attendings at Tufts-New England Medical Center in Boston, and his career path was established. Dr. Jeffery Isner was a pioneer in gene therapy and the revascularization of an ailing heart, who would himself die of a heart attack at age 53. Dr. Peter Libby, long-time chief of cardiology and Mallinckrodt Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, was and is a pioneer in vascular biology and atherosclerosis. Libby has received top honors from groups like the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology and is an editor of the trusted textbook “Braunwald’s Heart Disease,” now in its 11th edition.

Perhaps as a holdover of his EMT days, he loved the immediacy of cardiology, particularly of interventional cardiology. “People come in with acute MIs, their EKG is widely abnormal, you go in and you open up the artery and boy you can’t beat that,” he says. “You need to be quick and decisive,” he says, calm and unafraid but never dispassionate. Basic science would fit well, too, for many of the same reasons.

“Your goal as an interventional cardiologist is to change what is in front of you. I would argue that basic science is trying to do the same thing. We are trying to figure out why something is and how to fix that,” says Annex, with a lingering passion that underscores why his recruitment to MCG this summer had clinicians and scientists alike smiling, and maybe why he smiles all the time, too.

Experience leads

He would find the peripheral vascular system a good place to study and to learn more about the pervasive problem of cardiovascular disease. He would learn in his subsequent years as a fellow then faculty member at Duke University School of Medicine that you need to prove whatever you find before you say it. In medicine that meant showing something that held in the lab also held true in humans, which he would also learn is definitely not a given.

Dr. Kevin Peters, now chief scientific officer at Aerpio, a biopharmaceutical company focusing on eye disease, started at Duke the same day Annex did. Their children were about the same ages and the new colleagues shared an interest in angiogenesis. They worked together, a little unofficially at first, exploring the confounding reality that growing new blood vessels from existing ones just does not always work out well.

Analytical Annex began to see angiogenesis as a two-edged sword. In fact, he and Peters would find some of these tiny new vessels on the edge of the atherosclerotic plaque, where no good could come of them.

But Annex has never considered falling on the two-edge sword. “The human condition is going to give us the answer and it is simply a matter of whether we are smart enough to ask the right questions.”

Assuming in clinical practice or research that we already have the answer is a problem, he says, and the answer often is that we don’t know as much as we think about either.

Annex leads

Annex came to MCG in August as chair of the Department of Medicine, after about 15 years at Duke and more than a decade as chief of the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine at the University of Virginia School of Medicine.

Even though he now leads MCG’s largest department, administration is definitely not his favorite word. But again, like his father who had a natural ability to fix things, looking at people and a situation and figuring out how to help both, continues to resound with the son.

As chair of the Department of Medicine — traditionally the largest department of any medical school — Annex wants to help MCG and its hospital be the people and place everyone wants to go to for complex medical care.

“There are only two academic medical centers in the Georgia,” he says pragmatically of a state that is consistently ranked in the top 10 in both population and population growth. “I have good people around me here and more coming.”

He’s already asked his faculty to tell him what they do best and what they want to do, and admits he likes the glossier ideas about the future.

“I want people excited about what they are doing,” says the new chair, who “absolutely” is excited about his role. Part of his work as the new boss, he says, is to take away the administrative burden — to take away those tedious, inevitable conversations about funding and facilities — and fuel enthusiasm.

Recruiting is another big part, especially in a department that needs to grow. Before he even officially arrived, Annex had already helped recruit three new scientists to the department and to MCG’s Vascular Biology Center. They include Dr. Joseph Miano from the University of Rochester, whose focus incudes the differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells and genome editing, including CRISPR (see page 23); Dr. Xiaochun Long from Albany Medical College, whose expertise includes vascular remodeling in disease; and Dr. Vijay Ganta, who worked with Annex in Virginia and whose studies include exploring the therapeutic potential of microRNAs in peripheral artery disease.

In his first “task” he has selected internist Dr. David Walsh as chief of the department’s new Division of Hospital Medicine, to build that program, which works to optimize the care of hospitalized patients.

Annex is strategically expanding residency and/or fellowship training in areas of need like pulmonology, with an aging population experiencing increased problems with respiratory conditions like pneumonia and COPD. The department has similar plans across all its divisions.

Finding it hard to separate from cardiology, Annex says a heart transplant program is an easy example of what needs to be built clinically — a short-lived effort occurred in the early 2000s at MCG — not just for the sake of doing the now decades-old procedure, but because it completes the care MCG and its hospital offer in the increasingly common, complex problem of heart failure.

Cancer, cardiovascular disease, immunity and inflammation, which touch all organs, are the future of both medicine and MCG, he says.

“I think those in a broad sense are what we will be working at. How to help the immune system protect us better without destroying our joints or our pancreas,” he says. “We have people describing inflammation all the time but it’s not going to really do us any good until we start analyzing it and understanding it from the human state.”

Snapshot: Dr. Brian Annex

Annex would graduate from State University of New York at Stony Brook in 1981 with a degree in biochemistry and start at Yale University School of Medicine that year. He completed his internal medicine residency at Tufts-New England Medical Center in Boston, his cardiology fellowship at Duke University Medical Center in Durham followed by an interventional cardiology fellowship at William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oaks, Michigan. He would join the faculty at Duke for 15 years, where he became vice chief for research and director of vascular medicine in the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine before moving to the University of Virginia School of Medicine in 2008 as chief of the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine and George A. Beller/Lantheus Medical Imaging Distinguished Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine. At UVA, he helped develop regional collaborations with other health systems and physicians, worked to strengthen clinical and basic science research and served as medical director of the UVA Health System’s Heart and Vascular Service Line.

He is a consulting editor for Circulation Research and the Journal of Clinical Investigation, an editorial board member of the Society for Vascular Medicine’s journal Vascular Medicine and an associate editor for the Journal of the American College of Cardiology: Basic to Translational Science.

He is secretary/treasurer for the Association of Professors of Cardiology; has chaired the American Heart Association’s National Research Program, a subcommittee of the National Research Council; has reviewed applications for the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Outstanding Investigator Award; and has served on multiple National Institutes of Health study sections.

He was elected to the prestigious, 134-year old Association of American Physicians, for leading physician-scientists in the United States, Canada and beyond, in 2015. He is a fellow of the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association and the Society for Vascular Medicine.

In the last 20 years he has had a leadership role in about 20 clinical trial initiatives, most exploring new treatment options for peripheral artery disease. The trials range from giving patients growth factor from the liver, an organ that can successfully regenerate itself, including making more functional new blood vessels, to comparative studies of the benefits of exercise versus angioplasty to improve blood flow and reduce leg pain.

His basic science lab, which is already up and running in Augusta, also has been continuously funded for about two decades. The new J. Harold Harrison, MD, Distinguished University Chair in Vascular Medicine brings five NIH grants to MCG, is currently principal investigator on two grants, PI on another multi-PI grant and a collaborator on two others.

Like the old adage he learned early of prove it before you say it, his latest NIH grant could provide more insight into why vascular endothelial growth factor, a natural signal for blood vessel growth that has been a logical focus of many studies trying to promote such, has so far failed to help patients and maybe what to do about that.

His group also will study microRNAs to try to harvest the power of good inflammation to treat peripheral artery disease.