For Dr. Aaron Bolduc, ’11, the first year of operation for the Augusta University Adrenal Center has been life-changing.

On the last Saturday in February 2020, Dr. Aaron Bolduc took a moment to pause as he stood in front of his peers during the annual Moretz Surgical Society Conference, inside the J. Harold Harrison, M.D. Education Commons on the Medical College of Georgia’s campus.

Then Bolduc, a fellowship-trained minimally invasive surgeon and surgical director of the Augusta University Adrenal Center, launched into his report on the center’s first anniversary. Among the initial slides: The center is one of only five in the nation — and the only one in the Southeast.

Then Bolduc, a fellowship-trained minimally invasive surgeon and surgical director of the Augusta University Adrenal Center, launched into his report on the center’s first anniversary. Among the initial slides: The center is one of only five in the nation — and the only one in the Southeast.

“Count them, five,” he said, gesturing to the map, “and we have one of the most advanced.”

For those who understand the impact of adrenal disease on families affected by it, Bolduc’s pride is understandable. Many people may live their entire lives never thinking about their adrenal glands. All of us are born with two of them, triangular-shaped organs measuring only about an inch high and two inches wide at their widest point, sitting just above our kidneys. When they work, our adrenal glands churn out hormones that keep our metabolism humming, help our immune systems fight off disease, regulate our blood pressure, and deliver boosts of adrenaline to help us cope with our busy, daily lives.

But when they don’t work as they should? Our bodies are no longer able to compensate under common, everyday stresses. Something as simple as a fever could throw us into an adrenal crisis, an emergency, life-threatening situation. Other forms of adrenal disease could also manifest as nonspecific, long-term symptoms like crushing fatigue, gastrointestinal problems or high blood pressure that either lifelong steroid therapy or surgery is needed to solve.

Adrenal problems are rare. For example, incidence of Addison’s disease, which can lead to adrenal insufficiency, is between 40 to 60 people per million. But it’s estimated that 1 in 10 men and women over 70 will be diagnosed with an adrenal tumor causing either no symptoms or symptoms that range from uncomfortable to life-ending. Family history can play a role, but in many cases, there’s no clear-cut reason why tumors or disease develop.

For these patients, getting diagnosed is the first hurdle that can take months, if not years. The next problem is finding treatment.

Fear of the unknown

Carrie Srnka guesses that it was about 2014 when she started getting her “digestive thing.”

She tried medicine; it didn’t work. She sought specialist help, thinking it might be ulcerative colitis, even Crohn’s; scans came back negative.

“Everyone said I was healthy,” she says.

But new symptoms kept coming. She started having pain in her gut that would never go away. She’d wake up in the middle of the night, panicked and flushed. Worse was how tired she was. “Lots of days, the fatigue just killed me,” she says, so much so that she wasn’t comfortable driving, worried that she might pass out at the wheel. “I found it was very cyclic throughout the day, and after 1 p.m., I’d go home to get office stuff done in the afternoons. It was just, ‘Get home, which way am I going to take to get there.’ It was alarming.” Worst of all, she says, “It was the fear of the unknown, why nobody could figure it out. Was this going to be my slow demise?”

Finally, after a colonoscopy, then an endoscopy and a follow-up MRI, she had an answer: a mass on her adrenal gland, and the likely cause of her strange problems.

But she’d never even heard of someone with an adrenal tumor. Based on his research, her physician suggested that the best route was to have it biopsied.

Srnka wasn’t reassured, and she decided to do some digging of her own first. She found completely opposite information, that a biopsy on an adrenal mass could be life-threatening. So, despite her doctor’s continued assurances, she did another search, this time for “top endocrinologists.” That’s when she found Dr. Carlos Isales and the Augusta University Adrenal Center.

Model treatment for adrenal disease

In many ways, Srnka was fortunate, says Isales, chief of the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism at MCG and medical director of the Adrenal Center. Even after they’re diagnosed, many patients find getting appropriate treatment problematic.

Often, it works this way: A patient is diagnosed with an adrenal issue, usually by chance, when a doctor orders a CT scan, MRI or ultrasound. Then comes a referral to an endocrinologist and more testing to find out the full nature of the problem. The endocrinologist may then contact a general surgeon to consult. Finding that right surgeon who is trained and comfortable with the complexities of removing an adrenal tumor can be another hurdle. Then comes pre-op and discussions with anesthesiology, and the entire process to schedule treatment can take weeks, if not months.

But at an adrenal center like Augusta University’s, that timeline is collapsed in many cases to a day or two.

Under the Adrenal Center’s multidisciplinary model, patients undergo screening in the morning, which could include a specialized dotatate PET scan designed for neuroendocrine tumors. Patients then see Isales, Bolduc and the research team together in one clinic room at the end of the day to review the treatment plan. “It’s very novel for this condition, which is so complicated and so much goes into it,” Bolduc says. “It’s also important to say that the Adrenal Center isn’t a bubble in this institution. We work with everyone,” including urologists, cardiologists, interventional radiologists, oncologists and anesthesiologists, who may all play a role in advising on or treating a single patient.

Besides treatment of primary disease, the model is good for patients’ mental well-being. “If the process of finding out what we’re going to do about it takes several months where the patient suffers unnecessarily, this streamlined workup and diagnosis reassures the patient,” says Isales, who describes the center’s process as the optimal practice of medicine. “It’s not only good patient care, but also beneficial to the patient psyche — as much as we all worry about bad things happening to us.”

Srnka was also lucky that an adrenal center was only 18 miles from where she lives in Aiken, South Carolina. With only five in the entire country, it’s not uncommon for patients with adrenal problems to travel hundreds of miles for care. According to Bolduc, over their first year, 254 patients were evaluated, 75 were enrolled in research studies and 15 patients underwent adrenalectomies —all of whom, in most cases, would have otherwise ended up traveling outside of the Southeast to find help. “We have patients from the CSRA, from Brunswick and South Carolina,” he said, pointing to map of Georgia and South Carolina dotted in red. “We had one from Oklahoma City a few weeks ago. So word is getting out, and we’re happy to take care of these patients.”

During surgery

Inside the operating room, a patient is prepped for the removal of an adrenal mass, surrounded by the surgical team and anesthesiology. Just outside the OR, Bolduc sits at the console of the da Vinci Xi, peering through a viewfinder while his arms manipulate instruments to perform the delicate surgery involved in dissecting an adrenal tumor.

The anatomical challenges of an adrenal dissection are immense. “It’s a small gland,” Bolduc told his audience during the Moretz meeting. “But it’s a gateway, a highway too. I didn’t appreciate that in residency, but what pops out of the adrenal gland is important because the next stop is the heart.”

Because Srnka’s research was correct: Adrenal biopsies can be quite dangerous since nicking the gland can create a heart-stopping surge of adrenaline. That can happen during surgery, too. The risk of an adrenaline surge is high both during anesthesia and surgical dissection.

Bolduc reduces that risk several ways. The team handling the anesthesia is selected carefully for experience in managing adrenal surgeries. Then there’s the da Vinci Xi, the fourth generation of the robotic surgery system, which Bolduc says allows surgeons to better visualize both the tumor and the surrounding anatomy so they can do a finer dissection. During surgery, Bolduc also employs an unusual “no-touch technique.” Before he ever attempts to remove a mass, he first ties off the vein leading from the adrenal gland to the inferior vena cava to help avoid that surge of adrenaline pulsing to the heart.

Robotics and the residency component

During his residency at MCG, Bolduc saw very few adrenal surgeries, but it took just one for then-Surgery Chair Dr. Daniel Albo to consider Bolduc for the position of surgical director of the Adrenal Center. “I did a pheochro-mocytoma [a rare tumor of the adrenal gland tissue],” Bolduc says.

“The management of the patient was pretty complicated, but we handled it very well and had a great outcome. That’s probably what put me on his mind.”

That surgery was done laparoscopically with Albo. At the time, MCG didn’t have any formal robotic education for its residents, says Bolduc, with most surgeons completing a weekend training in robotics.

That’s now changed, thanks to the Adrenal Center and the da Vinci Xi. MCG classmates Bolduc and Dr. Renee Hilton, chief of the Division of Minimally Invasive Surgery at MCG, have developed a residency training program that provides an online course covering the robotic components, a dry lab allowing a resident to practice instrument exchanges and docking afterhours, then tasks on a simulator followed by 10 bedside cases as the first assistant. When they are competent to perform the majority of cases, residents are then officially certified by MCG for robotic surgery.

The training has been in place for more than a year and is available not only to general surgery residents but also those in urology, otolaryngology and obstetrics and gynecology.

The curriculum has been a huge benefit to surgical residencies, says Bolduc, not only meeting residents’ demand for robotic training but also enabling residents to immediately jump into surgeries at training sites outside of MCG and meet demand at rural hospitals for more general surgeons.

Very few studies have surveyed the status of robotics training in general surgery residency, but the most recent, from 2013, found that only 63% of residents have participated in a robotic case and 60% of those did not receive any robotics training prior to participation.

“Personally, I feel it’s very important to know the tool before going out and using it,” said Bolduc during his presentation, “not trying a new toy out with no good preparation. So by training residents, they’re not only understanding how it works and getting troubleshooting tips, but those who do it get broad exposure to robotic cases and better training.”

Rare research

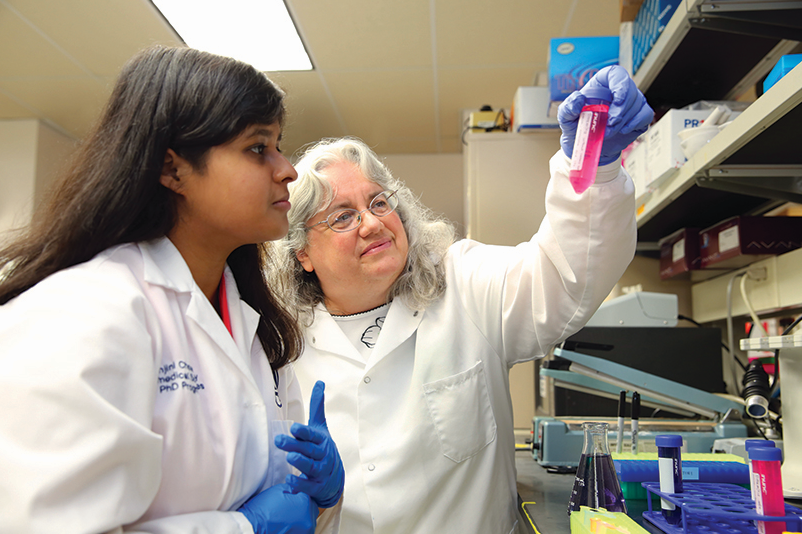

A final and key piece of the Adrenal Center is research. Due to the rarity of adrenal disease in the general population, every patient at the Adrenal Center is invited to participate in research, says Isales, such as donating blood or other samples to MCG’s biorepository, or tumor bank. As the center’s research director, cell physiologist Dr. Wendy Bollag takes the lead on coordinating those efforts.

For Isales and Bollag, their partnership in the Adrenal Center is a continuation of the working relationship they had when both were in the same lab at Yale School of Medicine early in their careers, Isales as a fellow and Bollag completing her PhD work. Then, they were working on similar research projects on the regulation of aldosterone secretion through calcium and lipid signaling pathways. Thirty-five years later, “it turns out they are both important,” says Bollag.

Aldosterone, one of the hormones secreted by the adrenal gland, is an important regulator of the body’s sodium levels and hence blood pressure. Too little, and patients’ blood pressure can drop, leading to fatigue and high potassium levels, which can affect your heart rhythms. Too much, and patients can experience high blood pressure or even resistant hypertension;

high aldosterone is also a risk factor for congestive heart failure, stroke and renal damage.

In fact, the center’s initial funding supported a pilot study by Dr. Eric Belin de Chantemele, a physiologist in the MCG Vascular Biology Center, looking at aldosterone as the culprit in why women often have worse outcomes than men after heart attacks.

Other studies are in the works too. After Bollag launched a monthly meeting to bring together MCG scientists involved in adrenal research, “it was like a lightbulb went off,” she says, as scientists quickly saw synergies with others at the institution. In fact, from one of these meetings, Bollag, Belin de Chantemele and Dr. Jennifer Sullivan, a pharmacologist and physiologist in the Department of Physiology, recently put together a pilot grant proposal to examine the involvement of aldosterone in obesity-induced hypertension.

“That’s one of the reasons we wanted to set up this adrenal research meeting,” she says. “We all have pieces of the puzzle. I’m hoping we can put them together to make a big puzzle…What I’m hoping with this Adrenal Center is that we’re not only doing research but will be able to translate that research to something that will help human health and in particular the state of Georgia.”

The Augusta University Adrenal Center is also a member of the American-Australian-Asian Adrenal Alliance, or A5, an international consortium of researchers and clinicians working to build data repositories and standard treatment guidelines for adrenal disease. In many ways, it’s a much larger version of Bollag’s monthly meetings. Prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, a team from the University of Michigan, one of the founders of the A5, was set to make a site visit at the end of April to assess the center and help with any improvements; at press time, that meeting has not been rescheduled. “Together, we’re stronger,” she says. “Together we’ll be able to better understand adrenal disease and hopefully better treat and prevent it.”

For patients, a new beginning

That’s good news for patients like Carrie Srnka, who suffered for years before the Adrenal Center diagnosed and treated her pheochromocytoma.

A year after surgery to remove the tumor, she says she’s still getting her function back as her hormones slowly rebalance. But the fatigue is gone, and so are most of her symptoms. She recognizes, too, the good fortune of the Adrenal Center and its team being right here in her community. “When you can find somebody to help you with this type of situation, plugging through it and finding it, it’s like, ‘Wow, I can get that done and be a different person on the opposite side?’ It’s pretty incredible.”

Family Matters

The Augusta University Adrenal Center probably wouldn’t exist, had it not been for the help of a family affected by an adrenal tumor.

In 2017, Curt Thompson’s son was diagnosed with a paraganglioma, a tumor of the adrenal gland tissue. The family was told there was no place in the Southeast to find treatment. So they traveled nearly 1,500 miles to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. While there, Thompson realized that in the waiting room with him were many other families from Georgia.

“This opened my eyes,” Thompson says. “Once we got our situation settled, I realized that we had to address that in Georgia, and the best way to do that was through Augusta University, through the medical college here because it is our state’s medical school. If we are going to be advocating for state money, it should be going to a public institution.”

Thompson, who is a former Georgia state senator, soon connected with Dr. Charles Howell, ‘73, CEO of Augusta University Medical Associates and then-chair of the Department of Surgery, and later, Dr. Daniel Albo, who became surgery chair when Howell stepped down in July 2018, to develop the structure and components of an Adrenal Center. Former Gov. Nathan Deal and the Georgia General Assembly also supported Thompson’s vision and worked to allocate funds to establish the center. Those funds would go on to support a multidisciplinary team including specialties such as surgery, endocrinology, cardiology, radiology, pathology, anesthesiology and research; the Intuitive da Vinci Xi robotic surgical system; a dotatate PET scanner, which uses a specific dye to identify neuroendocrine tumors; and the Adrenal Center core staff, including Bolduc; Isales; Bollag; Howell as an advisor; and Nicki Martinez de Andino, nurse practitioner.