You’re more likely to get struck by lightning than to have an ocular stroke. Bill Jones hasn’t been struck by lightning, but he has been struck by an eye stroke — twice.

The first, in 2018, wasn’t caught in time and cost him the vision in his right eye. When the second one happened in 2021, MCG ophthalmology and neurology specialists were able to act quickly and save his remaining vision. Using a microcatheter guided through the tiny blood vessels in his eye, they delivered the clot-busting drug tPA — an approach similar to one that’s long been used to treat big ischemic strokes in the brain — but instead they pull the clot out.

MCG and its adult teaching hospital AU Medical Center is the only place in Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina that performs this sight-saving procedure.

“You’ve heard of a stroke

“You’ve heard of a stroke

because most (clots) go to

the blood vessels in the

brain. It’s the same exact

thing, with the same risk

factors. (The clot) just goes

to the eye instead.”

–Dr. Zachary Lukowski

It just went black

Jones, 80 of Augusta, was browsing his laptop in 2018 when two pages with strange shapes suddenly appeared in front of his eye. “Then it just went black,” he remembers. “It was almost like someone pulled a curtain down. It wasn’t like I just couldn’t see clearly, it was like my eye wasn’t even there.”

He’d had an ocular stroke, characterized by sudden, painless loss of vision. Most happen when a tiny piece of fatty plaque that’s built up on the carotid artery in the neck breaks off and travels to the eye through the ophthalmic artery, which branches off the carotid. People with high blood pressure, like Jones, heart disease and diabetes, are most at risk.

“You’ve heard of a stroke because most (clots) go to the blood vessels in the brain,” says Dr. Zachary Lukowski, MCG vitreo-retinal specialist. “It’s the same exact thing, with the same risk factors. (The clot) just goes to the eye instead.”

Jones felt lucky to get a last-minute appointment with his regular optometrist later that same afternoon, but “They looked at the eye and said that there was nothing wrong,” he remembers. “I told them there may not be, but I can’t see out of it.”

Time was the enemy.

Preventing long-term damage from any stroke is a race against time. Mere minutes count when it comes to clearing a blockage and restoring normal blood flow, and hopefully function, whether it be in the eye or the brain.

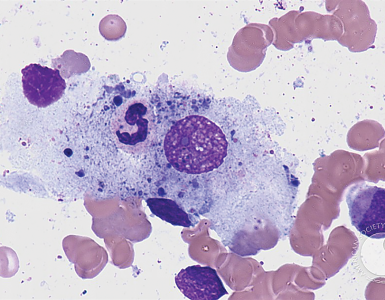

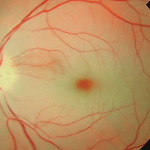

When Jones saw Lukowski, the damage was done. “He had a total occlusion of the retinal artery, which has a very classic appearance of a cherry red spot when you look into the eye,” Lukowski remembers. The vision loss caused by the long-term blockage was permanent.

Jones, who says his faith has always sustained him, accepted the news with his usual grace, thankful that with a new prescription for glasses, his other eye was able to compensate, and he could carry on with life mostly as usual.

A new and better way

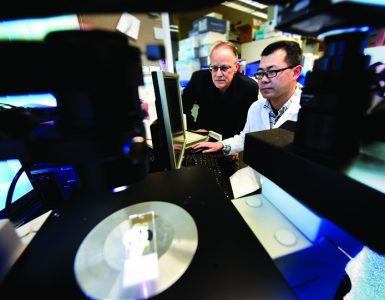

Around the same time Jones had his first ocular stroke, the MCG Department of Neurology was recruiting Dr. Dan-Victor Giurgiutiu with an eye toward continued expansion of the medical school and its teaching hospitals’ Advanced Comprehensive Stroke Center. The interventional neurologist traces his interest in his field back to his residency at Harvard Medical School, when endovascular treatment — the use of microcatheters to remove or dissolve clots from blood vessels — was first being explored as a new way to treat stroke.

“We would see these people with occlusions of these big vessels in the head and we’d watch them lose the ability to use half of their body, to speak or to take care of themselves. It was very sad,” Giurgiutiu remembers. “Then, there was great promise that this type of procedure could reverse this — people would come in not being able to speak and wake up from a procedure saying ‘Hey, what’s going on?’ I latched on to that promise.”

He pursued a vascular fellowship at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center; and a neurointerventional fellowship there after that. The initial clinical trials demonstrating the success of endovascular treatment to treat stroke in the brain were being published as he was finishing his second fellowship in 2015.

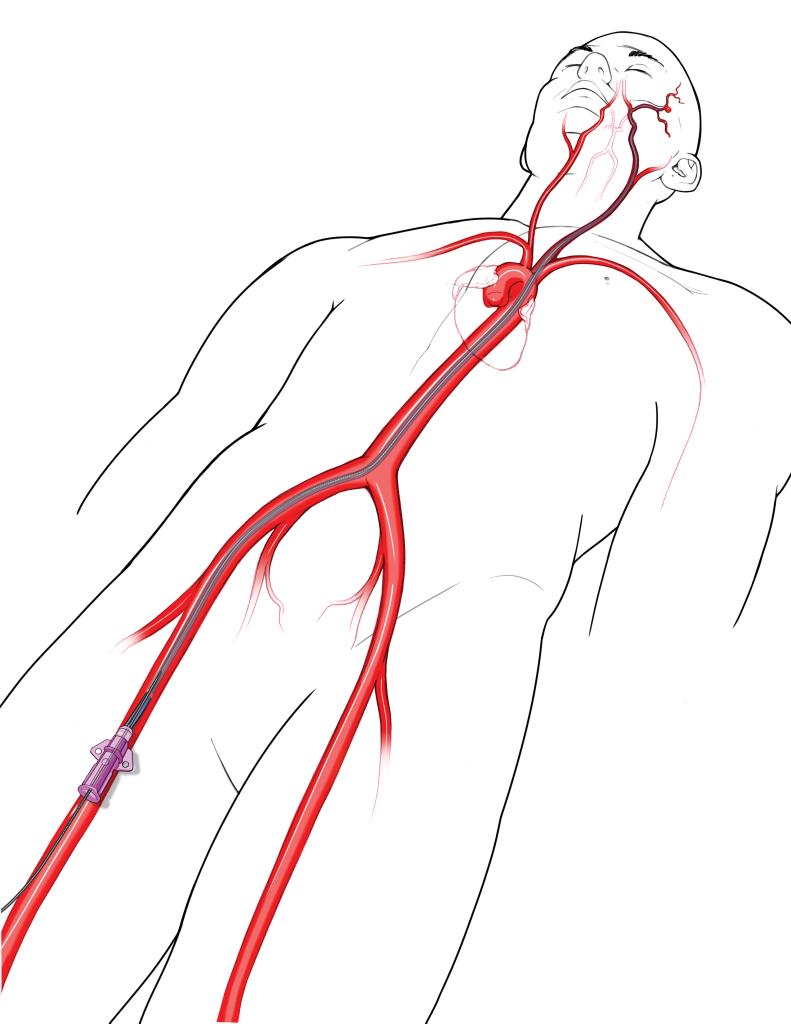

Trials showing its efficacy in ocular strokes — where neurologists access the femoral artery through the right groin, place a thin tube in a patient’s carotid artery and then thread a catheter the width of the wire of a paper clip through the carotid and into the tiny blood vessels in the eyes — have been harder to come by.

“Eye strokes are so rare (happening to about 1 in 100,000 people) that getting enough people in a clinical trial to demonstrate its success is difficult,” he says, noting that about 50-60% of people treated this way recover some, if not all, of their vision.

When he joined a small neurology practice in Winchester, Virginia, after training, he set changing that as one of his first priorities. He worked to build a network of care providers — ophthalmologists, optometrists and even primary care physicians — who would send any patients experiencing sudden vision loss to him, in hopes of just increasing the sheer number of people who benefited from this treatment of their eye strokes. “But it was a smaller town, so it was easier to do that.”

Admittedly, part of what drew him to MCG and AU Medical Center three years ago was the reach of the Advanced Comprehensive Stroke Center, with its existing network of rural hospitals and referring physicians, its responsive and skilled approach to stroke care and the potential to provide — and eventually validate — endovascular treatment of eye strokes.

“There already is a streamlined process if someone comes in exhibiting symptoms of stroke,” Giurgiutiu says. “The CT scanner is cleared, they’re registered in the hallway rather than going to a room. They go for a scan right away and they’re given (the clot-busting drug) tPA within 10-20 minutes. If they’re not a candidate for tPA or have the type of stroke that needs further treatment, they are assessed for endovascular. That decision is made within half an hour of them walking through the door.”

That is exactly what needs to happen when someone presents with an eye stroke and he and Lukowski are fine-tuning a protocol so it does — every time.

“The American Heart Association has come out in support of this treatment of eye strokes, saying we should recognize this as an emergency. We want to build on that,” he says. “The treatments that we’ve tried before, which have included things like the hyperbaric chamber, which is pretty hard to set up, eye massage and draining fluid from the eye, they don’t really help. We need a trial with large numbers of people to prove that there’s a significant improvement with this treatment.”

Lightning strikes twice

In January 2021, Bill Jones was sitting in his breakfast room eating lunch when some crumbs from his sandwich began to tickle the back of his throat. He began violently coughing and suddenly “it was like splat! It was like someone threw paint over my eye.”

Just like three years before, his vision was suddenly and painlessly gone — save for the ability to see some light around the edges of objects. Knowing he was likely dealing with another eye stroke, Jones called Lukowski’s office where he would be seen that day. “As we were getting ready to go, I did pray and tell God that I’d deal with whatever I had to, but I hoped he had another plan for me.”

This time Lukowski and Giurgiutiu had another plan, too.

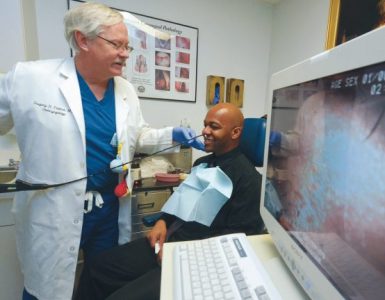

In the ophthalmology clinic, Lukowski peered into the back of Jones’ eye, suspecting a branch of the retinal artery, as opposed to the entire artery, may be blocked this time because Jones could at least see something. “This is a little bit of a challenging diagnosis to make, because it’s not the whole artery. When the whole artery is occluded it’s an obvious diagnosis,” he says. “I had to do an angiogram of his retina, just to verify that was actually what was going on.”

Lukowski discovered a blockage in a critical branch of Jones’ eye, in part of the retina called the fovea, where the cone photoreceptors that allow for sharp vision and color vision are the densest.

Knowing time was finite and the best results would come, like with the brain, within 4-6 hours of the stroke, Lukowski immediately called Giurgiutiu. “I told Mr. Jones there could be a little bit of risk with this procedure, but if you don’t try, you’re going to be blind,” Lukowski says in his usual matter of fact way.

Needing no convincing, Jones quickly agreed. The rest of the day was a flurry, he remembers.

He went directly to the emergency room and images of the blood vessels in his eye went directly to Giurgiutiu. Suddenly his room began swarming with people — medical students, residents, fellows. A nurse quickly started an IV and administered a rapid COVID-19 test via a nasopharyngeal swab, which came as an unpleasant surprise to Jones.

Giurgiutiu told Jones’ wife Margaret to go home — COVID restrictions meant she could not stay with him. Giurgiutiu would call her in a few hours.

Jones was sedated and quickly rolled to the biplane cath lab where two cameras rotated around him, giving Giurgiutiu 3D images of his blood vessels in real time. Giurgiutiu followed the path of blood flow through the vessels and created a “roadmap” for reaching the blockage, then delivered the clot-busting drug. Jones was sent to the neuro-intensive care unit overnight.

“The nurse called me in the middle of the night to let me know he was doing fine,” Margaret remembers. “She told me he said he could actually see and that he was restless and pulling at tubes.”

Jones just remembers waking up the next morning and “I could see fine. In fact, the nurse joked that I was too nonchalant about my vision being saved, but I told her I had just had faith this was going to work from the beginning.”

He was rolled from ICU back to the ophthalmology clinic and Lukowski for a follow-up exam and went home later that day with just a freckle-sized scar on his inner thigh, instructions to see Lukowski for regular follow-up every six months or so and to keep working with his primary care physician to mitigate his risk factors like uncontrolled blood pressure and high cholesterol.

“I’ve had a lot of health problems and I’ve always said that if it weren’t for God and good doctors I probably wouldn’t be here,” Jones says laughing. “Thanks to this I have been able to continue to live a normal life. I am so thankful.”

Next steps

The biggest need now, both Lukowski and Giurgiutiu say, is educating more people that this treatment is available, and making sure they know where to get it.

“The bottom line — what we want people to know most is that they should come to a center that knows how to best treat stroke and does it emergently,” Giurgiutiu says. “Your eye is a part of your brain and just like we have good ways to treat strokes in the brain, we can treat this. Twenty years ago, people didn’t understand that you could treat a stroke in

the brain, but now you can get to the ER and we can do things to help.

The same thing applies to eyes. People need to understand that if they get to the ER quickly, we can help you.”

They are working now to build a network similar to the one Giurgiutiu was building back in Winchester, but with a broader reach. He notes that with the Central Savannah River Area’s population of nearly 768,000 people there is the potential to treat about 60 people a year who have had ocular strokes.

“Then you build a network of hospitals that can do this and the hope is that you can get effective results quickly to show this is a viable treatment,” Giurgiutiu says. “We treat stroke more aggressively now than we ever did in the past and we have much better outcomes. Now we have this method and if people can become aware, we can prove that this can work for eye strokes as well.”