AMERICA’S CHILDREN ARE IN CRISIS.

SUICIDE IS THE SECOND LEADING CAUSE OF DEATH AMONG 10-24 YEAR-OLDS.

ADHD, anxiety, behavior problems and depression are the most diagnosed mental disorders in children, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Between 2016-19, among children ages 3-17, 6 million were diagnosed with ADHD; 5.8 million with anxiety; 5.5 million with behavioral problems like inattention or impulsivity; and nearly 3 million with depression.

Around 1 in 44 children has autism spectrum disorder, according to the CDC. In 2000, that number was 1 in 150.

In the past year in Georgia, 11% of children in grades 6-12 reported self-harm; 12% seriously considered suicide; and 6% — or nearly 13,000 — attempted it, according to the Georgia Department of Education. Nearly 120 children in the state died by suicide last year.

The statistics are staggering and help is scarce.

In this country, more than 150 million people live in federally designated mental health professional shortage areas. In Georgia, 14 counties have no child and adolescent behavioral health services. All 120 of the state’s rural counties have a mental health workforce shortage. The same is true for 30 of the state’s 40 nonrural counties.

There are only 700 developmental pediatricians in the entire country.

With a recent $5.3 million gift from the Kevin and Brittany Kisner Foundation to help lay the groundwork for a new Center for Pediatric Development, Behavioral Health and

Wellness, leaders at the Medical College of Georgia and Children’s Hospital of Georgia hope to begin changing these dismal statistics. The center would combine services like developmental pediatrics, pediatric neurology, psychiatry and psychology together with rehab services like physical, occupational and speech therapy, under one roof, creating a one-stop-shop that would serve children and their families, from diagnosis through ongoing treatment, regardless of their ability to pay.

Blown out of the water

These are not new problems, but they are bigger ones.

The American Academy of Pediatrics, the Children’s Hospital Association and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry together in 2021 declared the mental health crisis in children had become a national emergency. Concern over the state of children’s mental health had been growing for at least a decade before that.

“There is an enormous need for children’s behavioral and mental health services, which was there before COVID-19 and was completely and exponentially blown out of the water by the pandemic,” says Valera Hudson, MD, ’85, chair of the MCG Department of Pediatrics and pediatrician-in-chief at CHOG.

The pandemic-induced social isolation, lack of access to school and friends, disruption of daily routines and general uncertainty, certainly led to increased stress and anxiety in children. “A lot of homes are still in crisis,” says April Hartman, MD, chief of the Division of General Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine at MCG. “People are stressed. You’re seeing parents who have lost their jobs. There’s been an increase in domestic violence.”

But Hartman also suspects part of the increase in the prevalence of these problems in children is also because there’s a better understanding of signs and symptoms that were probably always there.

“A lot of the reason we see more and more cases is because we recognize (these issues) now, and we identify (them),” she says. “Learning has changed and what we require of our kids much earlier is different. When I look back at what we used to do in school, we didn’t have algebra until high school. Now it’s being taught in middle school. I think things like that bring out the differences in people earlier.” The kid that used to just be the “quirky one” in class, may today be diagnosed with ADHD or even autism, for example.

Social influences have also certainly changed. TVs, which used to be relegated to the living rooms, have long since moved into bedrooms and now many children have access to the internet at their fingertips on phones and tablets 24 hours a day, seven days a week. “It’s tough for families to regulate that and kids probably aren’t getting the sleep they need. It also creates the opportunity for kids to develop unrealistic expectations from what they see on social media, not to mention opening up the door for cyberbullying and all sorts of other issues,” says Dale Peeples, MD, child and adolescent psychiatrist at MCG.

“Some of this is specific to the US and our culture, which if you just read the headlines, you can see that we live in very tumultuous, challenging, divided, adversarial times with gross inequities in wealth between the top one percent and everybody else,” adds Hudson. “Every country isn’t dealing with the same thing we’re dealing with.”

Nearly 20% of children in the United States have mental and behavioral health issues – and those are just the reported cases. About one in six, or about 17%, of children have been diagnosed with one or more developmental disabilities.

Things are even worse if you’re poor.

Among children living below 100% of the federal poverty level, more than 22% have a mental, behavioral, or developmental disorder and age and poverty level affect the likelihood of children receiving treatment for anxiety, depression or behavior problems, according to the CDC.

When children and families can and do seek treatment, just as is the case for signs of physical illness, the first place they often go is their pediatrician. “When I was in training and in my early days in practice, (general pediatrics) was more disease focused. Cure the pneumonia or treat the ear infection. Stop the runny nose,” Hudson remembers. “Now it’s anxiety, depression, it’s about school performance, about ADHD. The practice has changed. Many (general) pediatricians in practice today were not trained to treat mental and behavioral health issues.”

Understanding the need is only growing, Hudson began to “really dream and dream big” about establishing a new center to address mental and behavioral health and pediatric development.

Ever the pragmatist, she knew what needed to be done, what should be done, but before the Kisner Foundation’s $5 million pledge to help sustain the center became a reality, Hudson and others knew they had to start somewhere. “We don’t always have the money and resources to do what we need or want to do. You can’t always wait for the big bang. We began to ask ourselves ‘What can we do now with what we have?’”

We had to start somewhere

What they had at the time was an initial $350,000 investment from the Kisner Foundation and they had Hartman.

Like most pediatricians, the Dorothy A. Hahn, MD, Endowed Chair in Pediatrics was seeing more and more children with mental and behavioral health issues in her practice. Having served on Behavioral Health Advisory Committee for the Georgia Chapter of the American Academy of Pediatrics since 2019, she knew that trend was only going to continue and had already begun thinking of ways to change how she approached and treated patients and their families in her practice.

The answer was something she calls PEPC — or Pediatric Enhanced Primary Care. She explains the clinic model as a “holistic, team-based approach. Telling children and their families ‘go there for your mental health and come here for your physical health’ doesn’t make sense. We do primary care, but we do it with a team that includes a psychologist. Psychiatry residents also spend time in our clinic. We have a different approach.”

She says the concept is simple enough — looking at the whole child, including any issues they may be facing, instead of treating a single problem. For example, a child who goes to school and is easily distracted may have ADHD, or they may be distracted because their parents are going through an ugly divorce and they’re caught in the middle, stressed out and can’t focus. “We try to take the time to tease out what’s really going on instead of saying, ‘Yeah, you’re distracted, let’s give you this medicine that will help you focus.’ Sometimes they do need that, but if it’s not ADHD maybe it needs to be treated differently,” she says. “When you start talking to children and their families, all of a sudden, it comes pouring out. Sometimes the kids and parents start crying because they just wanted someone to listen.” If children and their families need additional resources beyond what the clinic can offer, Hartman and her staff help them find them.

“Telling children and their families ‘go there for your mental health and come here for your physical health’ doesn’t make sense. We do primary care, but we do it with a team that includes a psychologist. Psychiatry residents also spend time in our clinic. We have a different approach.” – Dr. April Hartman

Changing how pediatricians think about and feel confident in treating mental and behavioral health issues has taken some education, including for Hartman — she earned a certification in integrated behavioral health from the University of Massachusetts Medical School in 2021. With the initial funding from the Kisner Foundation, her clinic has since been able to hire a psychologist and another pediatrician with additional training in primary care behavioral health.

Hartman is also sharing the medical school and its teaching hospital’s resources with pediatricians in the community.

Twice each month, she and other area general pediatricians talk with child and adolescent psychiatrists from the MCG Department of Psychiatry and Health Behavior in a meeting they call

Curbside Consultations. The pediatricians can ask about cases and MCG faculty offer some tips to determine if those can be handled at a primary care level or if they may need to be referred to psychiatry.

In February, the Department of Pediatrics, with funding and collaboration from the Pediatric Healthcare Improvement Coalition and Resilient Georgia, also offered, for the first time, a three-day REACH Institute Training to community pediatricians. The REACH, or Resource for Advancing Children’s Health, Institute is a nonprofit founded to ensure the most effective, scientifically proven mental health care reaches all children and their families.

Its patient-centered mental health in pediatric primary care program trains clinicians to diagnose and treat mental health conditions they see every day in practice. The program teaches them to manage the most common issues themselves, saving referrals to mental health specialists for complex cases. Participants also learn how to refer families to appropriate support services.

They also learn about a wide range of topics, from assessing and treating anxiety disorders, trauma and suicidality to managing depression and how to get the most out of medications.

The goal of REACH training is making pediatricians more confident in their diagnosis and treatment of mental health issues, according to the REACH Institute, which says the program has “transformed the practices of 4,000 physicians.”

It could also transform the lives of a lot of children.

“Seventy-five percent of kids experiencing problems go to their primary care doctor first, because that’s who they’re comfortable with,” says Eric Lewkowiez, MD, a child and adolescent psychiatrist at MCG who also chairs the Georgia Behavioral Health Reform and Innovation Commission’s Subcommittee on Children and Adolescents.

It’s also tough to get in to see a psychiatrist, with wait times that can vary from three months to more than six, depending on where you live.

“Fifty percent of mental health illness issues happen before the age of 14. If we can address the issues at that age, we’re going to minimize the progression,” he says. “We’re going to give them a fighting chance.”

The Big Bang

As a former speech language pathologist at CHOG, Brittany Kisner became all too familiar with how hard it could be to get children and families the help they needed, so they’d have that fighting chance. “I remember seeing so many families who didn’t know who to call, how to call or how to even navigate the support services they need,” she says. “There are so many children that fall through the cracks simply because there is no one there to coordinate services. No one there to diagnose them.”

Now a mother of three young children herself, that both inspires and terrifies her. “More so even now, just understanding how hard it is to be a parent, how hard it is to be a child right now. There’s no one who’s untouched by this (mental and behavioral health crisis in children). In some sort of way, if you have a child, you can most likely bet that you will be affected.”

When Hudson approached Brittany and her husband, Aiken native and PGA golfer Kevin Kisner, with the proposal for a new Center for Pediatric Development, Behavioral Health and Wellness at CHOG, Brittany knew instantly it was a perfect fit for their eponymous foundation. The Kevin and Brittany Kisner Foundation is focused around three main priorities — helping children with access to sports, better educational programs and better health.

Hudson’s vision for the center was impressive — a one stop shop, under one roof, where physicians, including developmental pediatricians, pediatric neurologists, child and adolescent psychologists and psychiatrists, speech, occupational and physical therapists, can assess and treat children for anything that impacts their mental wellbeing, whether they are born with it or develop it. “My ultimate dream, which may be pie in the sky, is a patient shows up (to the center) and has an assessment and we tell them ‘You know what? You probably need to start with the psychiatrist,’ or ‘You really need to see the developmentalist because that is where your primary problem is,’” and then they are sent there, Hudson says. “The structure we have now is so splintered and fragmented.”

“We are all talking about this crisis with children. I just don’t know what we’re adequately doing about it. This is the answer — creating more services, centers like this that can diagnose and treat more people and can provide more services and more resources for parents who don’t have them.” – Brittany Kisner

The Kisner Foundation committed to an additional $5 million endowment to sustain the center, bringing their total gift to $5.3. million. An additional $4 million will need to be raised to renovate existing space to give the center a physical home.

“We are all talking about this crisis with children. I just don’t know what we’re adequately doing about it,” Brittany Kisner says. “This is the answer — creating more services, centers like this that can diagnose and treat more people and can provide more services and more resources for parents who don’t have them.”

With the initial funding Hudson and others at CHOG have been able to begin laying the groundwork for the new center, including hiring Jennifer Poon, MD, who will serve as the center’s director. A developmental pediatrician Poon’s clinic had a waiting list almost as soon as she arrived in 2022.

A native of North Augusta who’s wanted to be a pediatrician since she was five-years-old, she came to MCG from the Medical University of South Carolina, where she also went to medical school, trained and had worked since 2011. Poon’s experience also includes serving on the executive committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics.

She says she too was impressed with Hudson’s vision and her clear and concise plan on how to get there. “That really attracted me to this position. I think this is also a great opportunity for collaboration. When services like this are siloed, even from a location standpoint, patients get fragmented care. If your office is just down from the psychiatrist’s office or the pediatrician’s office, the hope is that you can more easily collaborate and share ideas.”

Ultimately, while the center is focused on diagnosis and treatment, Poon says she has hopes it will be about something much bigger than that. “While we make these diagnoses, we’ve got to celebrate who the child is. At the end of the day, that’s who the family is taking home. Their child who they think is special and awesome. We’ve also got to think of ways to capitalize on children’s strengths.”

It’s a philosophy both Hudson and Kisner share as well.

“I hope as we advance and gain more insight, that we can move into prevention and we can help children thrive as opposed to treating illnesses that are already there,” Hudson says, explaining why she specifically wanted the word “wellness” in the name of the center.

“If we can provide better care and coordination of care, most of those children will go on to be successful adults and live normal lives and be productive and happy,” Kisner says. “That’s all I want for my children — to be happy, confident adults who contribute to society in some way.”

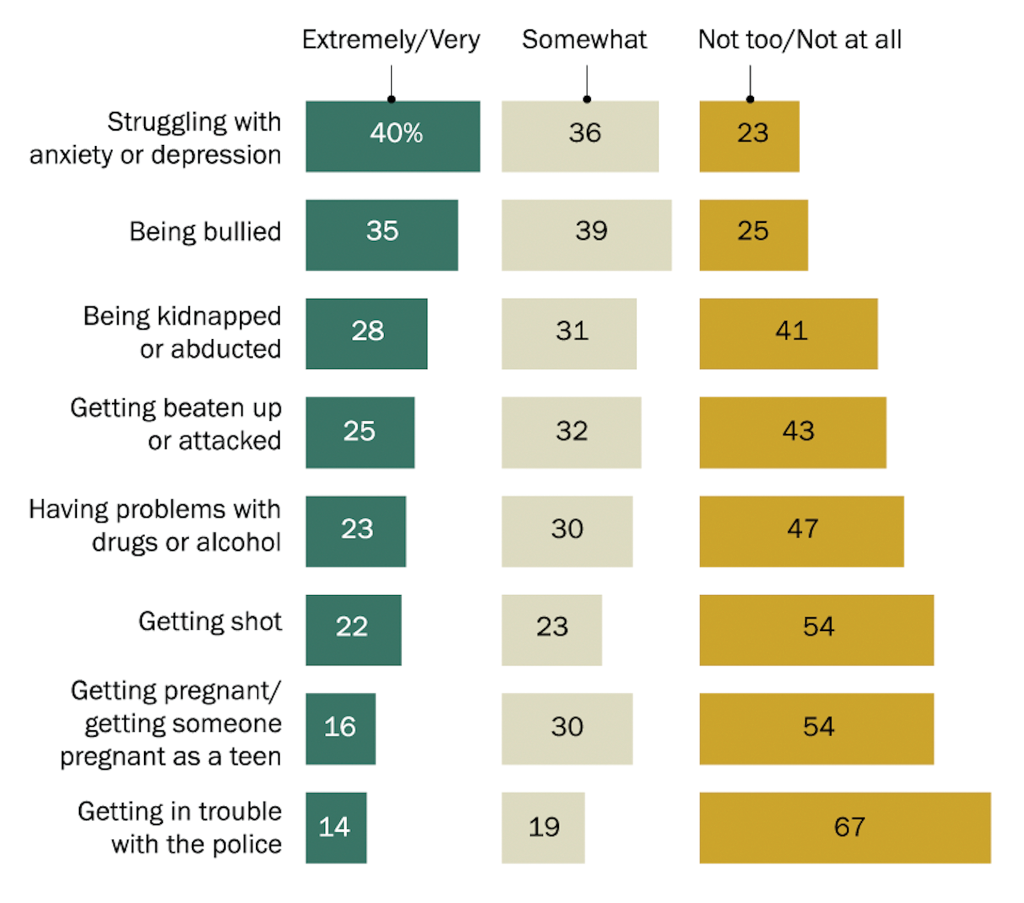

In January, the results of a new survey by the Pew Research Center showed that “four-in-ten U.S. parents with children younger than 18 say they are extremely or very worried that their children might struggle with anxiety or depression at some point. In fact, mental health concerns top the list of parental worries, followed by 35% who are similarly concerned about their children being bullied…”

Parents worried more about those issues than physical threats to their children, the dangers of drugs and alcohol, teen pregnancy and getting in trouble with the police, the report said.

STARTLING STATISTICS

ADHD, anxiety problems, behavior problems, and depression are the most commonly diagnosed mental disorders in children. Estimates for ever having a diagnosis among children aged 3-17 years, in 2016-19, were ADHD 9.8% (approximately 6 million), anxiety 9.4% (approximately 5.8 million), behavior problems 8.9% (approximately 5.5 million), and depression 4.4% (approximately 2.7 million)

Some of these conditions commonly occur together. For example, among children aged 3-17 years in 2016:

- Having another mental disorder was most common in children with depression: about 3 in 4 children with depression also had anxiety (73.8%) and almost 1 in 2 had behavior problems (47.2%)

- For children with anxiety, more than 1 in 3 also had behavior problems (37.9%) and about 1 in 3 also had depression (32.3%)

- For children with behavior problems, more than 1 in 3 also had anxiety (36.6%) and about 1 in 5 also had depression (20.3%)

1 in 6 children aged 2-8 years has a mental, behavioral, or developmental disorder

Depression and suicide are a risk for older children and teens:

- Among adolescents aged 12–17 years from 2016-19, 1 in 5 (20.9%) had ever experienced a major depressive episode.

- Among high school students in 2019, more than 1 in 3 (36.7%) reported feeling sad or hopeless, and nearly 1 in 5 (18.8%) seriously considered attempting suicide.

- About 7 in 100,000 children aged 10–19 years died by suicide in 2018 and 2019.

Source: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

For information on how you can contribute to the Center for Pediatric Development, Behavioral Health and Wellness, contact Catherine Stewart, director of philanthropy at the Children’s Hospital of Georgia, 706-832-1804 or castewart@augusta.edu; or Mary McCormack, associate vice president for gift and estate planning, 706-540-2885 or mmcormack1@augusta.edu