Betty and Lovick Corn’s extraordinary endowment 20 years ago to MCG pediatric cancer researcher Dr. David Munn continues to bear fruit

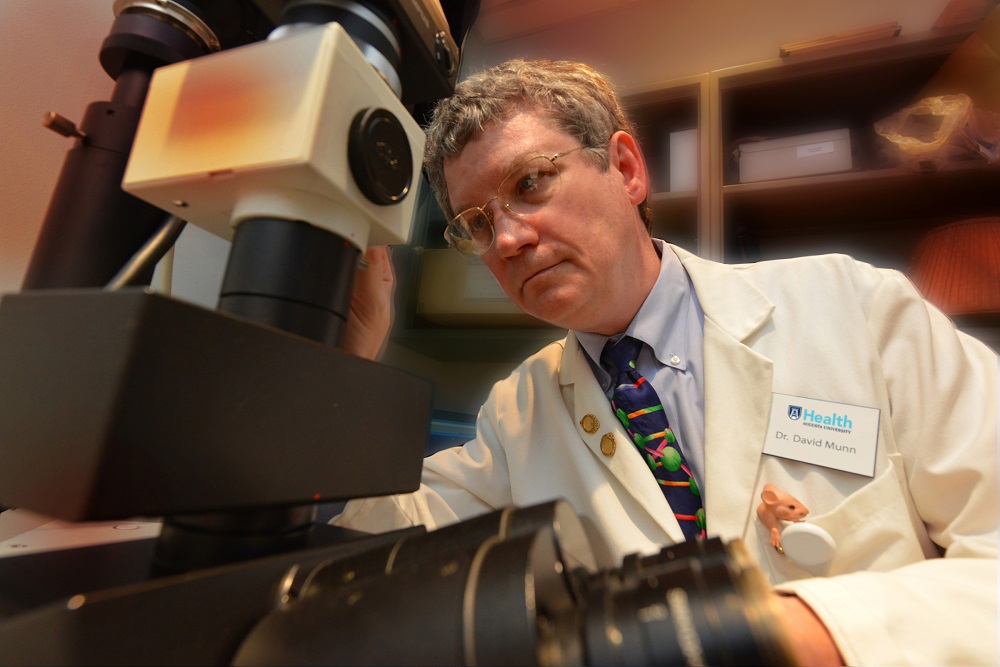

It was 2002, and Dr. David Munn, ‘84, a pediatric cancer researcher at the Medical College of Georgia, walked into the President’s Conference Room in the G. Lombard Kelly Administration building for a meeting with Betty and Lovick Corn of Columbus, Georgia. The older Southern couple was gracious and lovely, recalls Munn. They were also asking him whipsmart questions about the research he was hoping to conduct to identify more effective and less toxic treatments for children with cancer.

He must have done something right. He left that day with a commitment for a $1.5 million gift from the Corns, which with subsequent giving has turned into $4 million to date.

On that extraordinary day, that gift by Betty and Lovick Corn was the seed, allowing Munn to pursue the research he most wanted to do. Now, just shy of two decades later — a blip in the timeline of most translational research — Munn’s pediatric cancer bench science has translated into clinical trials, which have helped extend life or provide improved quality of life for children from around the world with the worst types of brain cancer. And he’s not stopping.

Funding hope

A photo of Betty and Lovick graces the office of Teddie Ussery, founder of Family Office Matters, who has helped manage the Corn family’s BELOCO Foundation and philanthropy for the past 40 years. Betty smiles graciously, while Lovick stands protectively over his wife.

Yet, if you look closer, there’s a sense of restlessness. The Corns — as anyone who knows them can surely imagine — appear to be pausing just for a moment, ready and eager to take on the next thing.

Lovick grew up in Macon, and Betty in Columbus. She was a Turner but also part of the W.C. Bradley family, which owns W.C. Bradley Co., still a manufacturing company and a major investor in The Coca-Cola Co. She also graduated from Wesleyan College and was determined to make a difference in her work as a community volunteer. He was the son of Emory-trained urologist Dr. Ernest Corn (one of the first in the field in Georgia), graduated from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, and served in the U.S. Navy during World War II in the Southwest Pacific Theater and the Philippines Campaign as commanding officer of the USS Apc42.

The two met on Sea Island after the war while their parents were vacationing there. Betty met Lovick’s brother Tom first, but it was Lovick who captured her heart. After their wedding in Columbus in 1949, they lived briefly in New York City while Lovick worked in sales for Bibb Manufacturing Company, but when Betty became pregnant with daughter Elizabeth, they came home, where Lovick joined the family company.

He would rise to become vice chairman at the W.C. Bradley Co. and of the associated Bradley-Turner Foundation and was also founder and chairman of the foundation he and Betty formed, the BELOCO Foundation. It was an inside joke, that name, whose letters were taken from their names, BEtty and LOvick COrn.

Both Betty and Lovick grew up with a strong family philosophy that they would pass on to their five daughters — “that we’ve all been tremendously blessed and we owe it to give back,” says Elizabeth Corn Ogie, who herself has served on the MCG Foundation. “We were raised, from the time I was little, [to believe that] you volunteer, you help in the community, you serve on boards, you give back. And that’s the broad family as a whole, the 100-plus of us all were raised that way” — and not only to give back but to do so with humility.

Originally, Betty and Lovick’s giving was generally focused on the arts and Methodist education. Pediatric cancer became a more specific interest thanks to Dr. Denny Hammond, a fraternity brother and close friend of Lovick’s, who headed the Division of Hematology/Oncology at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, served as group chairman of the Children’s Cancer Study Group, and was president and CEO of the National Childhood Cancer Foundation, now known as CureSearch for Children’s Cancer. The Corns often traveled to California to visit Hammond and his wife Polly, which is when Hammond and Lovick would no doubt swap stories of their work.

“Back in the day, pediatric hospitals each did their own treatment for different childhood cancers,” explains Elizabeth — meaning that a child in Minnesota might not receive the same advanced treatment a child in, say, California might. In the late ‘90s, Hammond was among the new thinkers at the time who wanted to ensure no children with cancer would needlessly suffer or die simply because a new treatment hadn’t yet been communicated to their region of the country. “Mama and Daddy bought into it, for sure,” says Elizabeth. “They had five kids and grandkids — and it just makes so much sense that the best protocol ought to be shared throughout the pediatric hospital networks.”

Then, their second daughter, Polly, was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma at age 30.

Polly’s son, Gilbert, was only 3 at the time. Although the cancer was even then highly treatable, Gilbert, now a father himself, can imagine what his grandparents went through knowing that their child — even their adult child — had been diagnosed with cancer. “I think when you start to look at the spectrum of this, she was young enough where you go, ‘Wait, she’s too young to get cancer.’ Then you find out, ‘Well, yeah, there’s kids that are two weeks old that have cancer.’

“My grandfather never talked at length about anything,” Gilbert says, “but what strikes me is this sense of justice in him and how he just felt like certain things were unjust. And I think they could see a mechanism to say, ‘We can help bring some justice to this by funding this and accelerating these studies so these parents and these kids have hope.”

All about the research

It was another family friend, Dr. Cecil Whitaker, ’62, who led the Corns to Munn at MCG. Much of the Corns’ giving was already locally focused, so supporting pediatric cancer research in their home state likely appealed. Whitaker, an OB/GYN living and practicing in Columbus, not only served as a member and chair of the MCG Foundation (and remains a chair emeritus), but he also is a member of the MCG Advisory Board.

Ussery believes that the uniqueness of Munn’s research also caught their attention. Immunotherapy was in its infancy at the time, and “the idea that it was a different strategy that had been thought about…it was a new idea … that would bring hope to this disease,” she says. “It intrigued them in that they wanted to see where this could go, and it was targeting pediatrics. Those two were the keys, I think.”

The meeting with the Corns couldn’t have come at a better time for Munn. Although he was and is a pediatric cancer researcher, he was then conducting research into cancer immunotherapy focused entirely on adult tumors, both melanoma and breast cancer models, funded by the National Institutes of Health. It’s a difficult fact, says Munn, but “the problem with developing new treatments for kids with cancer is that there’s not really a funding constituency for basic research on kids with cancer because children don’t constitute a large market.”

About 16,000 new cases of pediatric cancer occurred in the U.S. in 2020, compared to more than 1.8 million new adult cases overall, according to the American Cancer Society. It can also be assumed that families of children with cancer tend to be younger, with less wealth accumulated and less ability to direct earnings into a foundation or other vehicle to support cancer research. “I think [my grandparents] saw in that a real opportunity to make a difference where there was not a perceived gap, but a real gap in funding relative to the need,” says Gilbert.

That need was to find better treatments. In Munn’s case, unlike chemotherapy, which must be quite different for adults than for children due to potential toxicities on growing bodies, the immune system works similarly in both adults and children. “So, the case we made to Mr. and Mrs. Corn was to put some funding toward the pediatric aspect and earmark it specifically just for developing pediatric approaches; then we could use the research we already were doing in adult cancers,” says Munn.

That research was for the immunotherapy drug indoximod, an enzyme and natural immune suppressor that Munn would develop to inhibit a specific pathway called IDO (indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase). Munn believed that using the drug in combination with chemotherapy and radiation would enable the immune system to better recognize tumors and aid the body in fighting the cancer and slowing tumor growth. The Corns’ gift was the turning point that allowed him and his team to, at last, laser their focus onto pediatric cancer.

Betty and Lovick also laid the foundation that has helped attract a broader base of donors for pediatric cancer research at MCG, including from Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation for Childhood Cancer and the Press On Fund, among others. After Lovick passed away in 2013, Betty also continued to personally support Munn’s work. Two years later, she saw the seed they planted together bloom: MCG’s Dr. Ted Johnson, MD/PhD, ’04, ‘07, a pediatric hematologist/oncologist, opened the first clinical trial of indoximod for children with relapsed brain cancer or a difficult-to-treat cancer called diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma or DIPG.

Gilbert still remembers the BELOCO Foundation meeting when the trial was announced. “We’d moved beyond thinking about something theoretically to something that actually might change and/or save lives,” he says. “While I can’t tell you what year that was, I remember it now. It’s always been one of those things where you want to use that story as the reason you do what you do, not the ones where it doesn’t work out because there are way more of those. … But when you hit on something like that, that’s where it becomes the magic for both your long-term commitment, as well as for these families.”

And Munn keeps going back to this: The Corns’ support is about much more than the clinical trial work.

“The Corns remain unique,” he says, “in that they have always seen the value of the discovery research. That’s not as common. There’s such an urgent need to try and fix the kids who have the cancer…and the donors tend to want to support at the clinical trials stage. That is very logical…But the problem is that if you only support at the clinical trials stage, then you don’t make new discoveries that drive the next generation of clinical trials and make things better… The Corns have always seen [that].”

Now, he says, MCG is actively planning to open additional clinical trials in children based on the basic science discoveries funded by the Corns. Those trials, with an anticipated start date of Summer 2022, will layer additional immunotherapy agents with indoximod to further activate the immune system and create a synergy that hopefully will further slow and shrink tumor growth. While Munn is unable to discuss the specifics of the two drugs, “this will be the first time this combination is tried anywhere, and it’s going to be in the pediatric population.”

And that is the power of the Corns’ ongoing giving, because what Munn is describing would have been unheard of even a decade ago: “It’s the first time ever — and it’s in kids.”

Legacy work

Lovick has been gone now for more than seven years, and at 94, Betty is no longer as active as she once was. But Elizabeth remembers how thrilled they were to be a part of this important research “at the beginning”: “I can remember them saying very clearly that the reason they cared so much about pediatric treatment and research is you can treat an adult and buy them 5, 10, 15 years, but a child — if you treat and cure them, then they have a lifetime. They thought that was a no-brainer.”

In March, Betty and Lovick’s family — the fourth and fifth generation, as they call themselves — gathered on Zoom to continue the work of the BELOCO Foundation and its founders, including their ongoing support of Munn’s pediatric cancer research. It’s exactly what Betty and Lovick would want.

“In many ways, I think my grandparents have left us a legacy of doing the work,” says Gilbert. “It’s almost leaving something ahead for us. We are now responsible for their legacy.

Their legacy is one that will continue to live on by the very nature of what they chose to give to, not because they built a building, not because they put a plaque in the ground by a tree. They are literally helping people like Dr. Munn give life and hope to other people. I cannot imagine a better legacy to steward than that.”

– Gilbert Miller

Donors to MCG’s Pediatric Immunotherapy Program

• BELOCO Foundation and Betty and Lovick Corn

• Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation

• Hyundai Hope on Wheels

• Cannonball Kids’ Cancer Foundation

• Press On Fund

• CAMFUND

• Northern Nevada Children’s Cancer Foundation

• Eli’s Block Party Childhood Cancer Foundation

• Gracie’s Hope

• Rally Foundation

• Miriam L. Halsey Foundation

• Other grateful patients and associated companies and foundations

For more information on giving to MCG’s pediatric immunotherapy program, contact Eileen Brandon at 706-721-2515 or ebrandon@augusta.eduor visit https://www.augusta.edu/giving/neversayno.php