Augusta University’s Medical Illustration Graduate Program helps artists and scientists save lives and find change without compromising their passions.

When Amy Carlsen gave birth to conjoined twins in the fall of 2005, she and husband Jesse never dreamed an artist would one day play a role in saving their children’s lives.

Like most conjoined births, their girls, Abby and Belle, were born sick.

The two shared part of a liver, and a portion of Belle’s heart was lodged in her sister’s chest. To make matters worse, the two also shared a portal vein – the blood vessel responsible for carrying most of the body’s nutrient-rich blood from the stomach to the liver. To survive, the girls needed to be separated. But in order for that to happen, surgeons at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, first needed some guidance.

Conjoined births are extremely rare – successful separations, even more so – so, to give the girls a fighting chance, the surgery team brought in medical illustrator Michael King to depict what surgeons might find under the girls’ skin.

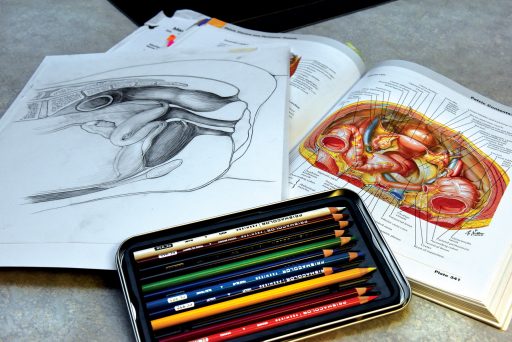

Using a mix of research, internal imaging and a pinch of artistry, King sketched a lifelike illustration of what Abby and Belle’s shared anatomy might look like. That sketch, used by the surgery team to perform a successful separation, was so uncannily detailed, in fact, that lead surgeon Dr. Christopher Moir later remarked, “What we encountered in surgery was precisely what [Michael] depicted in his illustrations.”

Now pushing 11, Abby and Belle Carlsen lead normal, happy lives with their parents in North Dakota. But their story, while unique, isn’t necessarily a rare one. Since the early 1900s, trained medical illustrators have helped to save countless lives by providing the surgical guides and learning aides used in operating theaters and classrooms throughout the world.

In 2005, though, Stephanie Pfeiffer (MS ’16) knew nothing about that.

Then a freshman at a visual arts magnet school in Savannah, Georgia, she had never considered art as a facet of medicine. Nor had she ever considered it a career.

“I was on the science side of things, and I knew I wanted to teach,” she explained. “I never really knew what opportunities existed for artists other than being the starving fine artist everyone hears about.”

So, when she enrolled at the University of Georgia in the fall of 2009 as an animal science major, no one was terribly surprised. After all, science and a love of animals had always been major parts of her life. Combining the two into a viable career path only strengthened her appreciation for both.

For a while, the choice felt like a good one. She enjoyed her classes, and the material was both challenging and stimulating. But after a few semesters, that feeling changed.

She didn’t feel stuck. Trapped wasn’t the right word for it. But something was off about her choice of major.

It felt like a compromise.

It was around this time that Pfeiffer’s older sister made a life-changing suggestion.

“My older sister was at UGA as an art and English major,” Pfeiffer recalled. “She recommended I take an Intro to Art class.”

So, she did.

In her art class, Pfeiffer met a student who recognized her appreciation for medical science. The student referred her to UGA’s scientific illustration program. Later, Pfeiffer spoke with the program’s director about pursuing a minor in scientific illustration.

From there, it was a short leap to a medical illustration graduate program.

But as many looking to jump into the field soon discover, there’s a serious shortage of landing points.

Only four programs in North America are accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs (CAAHEP): the Biomedical Visualization program at University of Illinois-Chicago, the Biomedical Communications program at University of Toronto, the Medical and Biological Illustration program at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the Medical Illustration Graduate Program at Augusta University. The task of finding the right program can be daunting. Though all four programs have their fair share of similarities, their differences far outweigh their parallels.

Pfeiffer’s choice was especially tough. She initially had an interest in Chicago and Toronto. By the time she applied to Augusta, she had already been accepted to Johns Hopkins. In the end, her decision came down to one thing.

“So, it’s really cold up north,” she said, chuckling to herself. “But, seriously, I chose Augusta because the program here really had the focus I was looking for.”

According to Amanda Behr, director of the Medical Illustration Graduate Program, that focus is one of the things separating Augusta graduates from medical illustrators the world over. It’s also not something you’d necessarily expect to hear from a professional artist.

“We focus on surgical training and the fundamentals of storytelling,” she said.

On the surface, the two disciplines – one a particularly hard science, the other an uncompromising art – might seem at first like a poor fit. Behr believes otherwise.

“I find that those who discover medical illustration as a career feel like they don’t fit in one place,” Behr said. “They love art and they love science. Some are scientists who have gone through all of their scientific training and realize something is missing. Then they find art.”

Behr understands that feeling better than most.

“For me, I went to art school first, found art, then realized I was really missing the science,” she said. “That’s one of the things that’s great about medical illustration. You don’t have to make a choice between the two.”

While applying surgical training to medical illustration might seem like a no-brainer (it isn’t, by any stretch), applying storytelling is, for many, a much harder task. But according to Peter Lawrence (MS ’16), all it takes is a change of view.

Like many of his colleagues, Lawrence has been drawing since he was old enough to hold a crayon. He, like Pfeiffer, also felt like his initial career path was a compromise.

But one major difference separates the two.

Unlike Pfeiffer, Lawrence said he never imagined life without art. It was the driving force behind his career decisions. It motivated him to stay in school, pushed him to succeed. Only, it wasn’t quite working out.

“I’ve always loved art, and I knew I needed to draw, so initially, I was a graphic communications major at George Mason University,” Lawrence said. “I did that for a couple of years, but it really just didn’t provide a lot of the creative satisfaction I needed.”

As a graphic communications major, Lawrence’s primary focus was design work: creating graphics, tools and interactive learning aids for children. It was honest work. And, to a degree, it was artistic. But it wasn’t a strong fit for his artistic voice.

It was at this point, confused and frustrated, that Lawrence found the change he needed.

“As I was just trying to find my voice as an artist, I found out one of my professors would actually do sketches in the operating room at a hospital affiliated with George Mason,” he said. “I just found that so intriguing.”

A fine artist at heart, Lawrence had always been interested in the human form, but to that point, he’d never considered medical illustration as a creative outlet.

[su_note note_color=”#efefee” text_color=”#000000″ class=”story-side-box”]

Speed Dating for Artists and Scientists

At Augusta university, bringing art and science together is part of the culture.

In February, Cheryl Goldsleger, Augusta University’s Morris Eminent Scholar in Art, hosted the university’s first Leonardo Arts and Science Evening Rendezvous (LASER).

LASER events are affiliated with Leonardo/The International Society for Arts, Sciences and Technology, a nonprofit organization serving a global network of distinguished scholars, artists, scientists, researchers and thinkers through programs focused on interdisciplinary work, creative output and innovation.

“This is a big deal,” Goldsleger said. “Top schools in the country host LASER events, including University of California, Berkeley, and Stanford University.”

The theme of the event was the influence of 3-D technology on visual arts and medicine.

Four panelists in addition to Goldsleger participated. Dr. Michael Schwartz, art history professor; Amanda Behr, interim chair and program director, Medical Illustration, and clinic director, Clinic for Prosthetic Restoration; Dr. Charles Clark, dean of the Pamplin College of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences; and Dr. Paul Weinberger, director of research in the Department of Otolaryngology.

The speakers talked about their individual occupations.

“It started to become obvious how each occupation overlapped,” Goldsleger said. “We didn’t speak to the particulars of that, but it was evident in each presentation.”

She described the event as “speed dating for artists and scientists.”

Goldsleger hopes the event will foster discussion between the art and science communities.

“The idea for this LASER was to get people to start talking and realize both campuses are active and we share common ground and common interests,” she said. “It may be in different ways and through different approaches, but we still have something in common. Two vital communities became one through the merger.”

Goldsleger believes the event was a success and estimates approximately 180 people attended.

“People seemed to be really engaged,” she said. “Our goal was to kick-start the process of building bridges and finding people with not necessarily the same exact interests, but interests that overlap, and finding that space where people meet and have knowledge, experiences and skills they can share.”

Goldsleger believes attendees saw ways in which education can be improved through the development of physical models. She is interested in learning about the ways in which researchers are using 3-D printers and how the medium has impacted their research.

Following the success of the inaugural LASER event, Goldsleger hopes to see the events continue. She would like to host four LASERs a year, two at the university and two in the community.

“The point of LASER is that it’s not a one-off event,” she said. “I’m hoping that the event allowed people to meet who have the potential to collaborate.”

The event also has the ability to teach students about the value of cross-campus collaboration at Augusta.

“It’s an important part of learning how to interact,” Goldsleger said. “If students are aware of that as beginners, then it becomes more normal to think of that as a possible way to work in later classes and when they graduate.”

Goldsleger is looking forward to future LASER events. She hopes to see an impact on the Augusta campus beyond the event itself.

“The event sparked a light, and it’s incumbent upon us to not let that light go out,” she said.[/su_note]

Following in his professor’s footsteps, he soon set about honing his own medical artistry.

He obtained permission to sketch in the OR and, eventually, began painting a series of illustrations depicting various surgeries. After some time, Lawrence’s then-girlfriend suggested he look into a medical illustration graduate program. So, he did.

“I looked into the program at Hopkins and thought to myself, ‘This is just perfect,’” he said.

Like Pfeiffer, Lawrence was also accepted into the program at JHU. He, too, declined.

“The people in Augusta were very friendly, and I really like the easygoing feel of being in a small city versus the hustle and bustle of Baltimore,” he said. “I actually reached out to several alums from each of the programs before making a decision, though.”

What he found only further cemented his decision.

“What I found from reaching out was that there are more alums from this program who have gone on to found their own successful medical illustration companies,” Lawrence said. “All the juggernauts of medical animation are alums of this program: companies like Radius Digital Science, Nucleus Medical Media and Vessel Studios.”

Lawrence entered the program shortly after. There, he discovered what it meant to become not only a “visual scientist,” but a storyteller as well.

The first step, he said, was to change the way he saw the “little things.”

As a fine artist, Lawrence had grown accustomed to including “minutiae” in his artwork. From figure sketches to paintings of surgical operations, he included every minor detail, every speck, freckle and dot he could to produce the most complete image possible.

After a few weeks in the program, however, he quickly learned why that was a problem.

“Whenever I mention medical illustration to someone who’s never heard of it, they always ask, ‘Don’t they have photographs of all that?’” he said. “It’s a fair question. Photographs catch everything on the surface. But you can tell a much more elaborate, complex story than just what a photograph reveals. It’s not about being picture perfect; it’s about creating understanding.”

Storytelling through medical illustration, he said, isn’t about producing the most complete image. It’s about explaining something to a viewer that can be understood at first glance, regardless of whether that viewer is a patient or a trained physician.

“It’s problem solving, really,” Lawrence explained. “There’s a particular message you need to convey, so you work through it and create concept sketches and storyboards to accurately address the issue so that someone can understand it just by looking at it. It was tough learning to cut out the nonessential, but it really improved my work.”

It was clearly a lesson Lawrence took to heart.

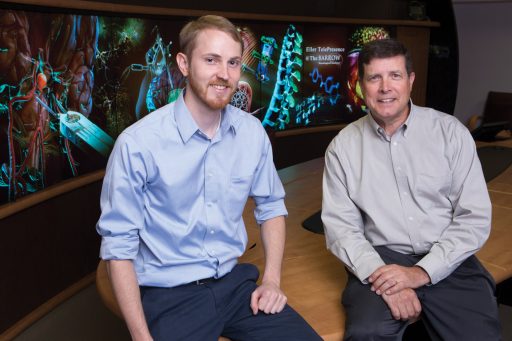

In June, he began a new career in the Neuroscience Publications office at the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix. There, working under the supervision of fellow Augusta medical illustration graduate Mark Schornak (MS ’87), he will produce artwork to assist students and professionals pursuing academic publishing.

For Lawrence, it’s something of a dream job — even if it is a huge change from his fine arts background.

“The first images I’ll be doing are for a neurosurgical atlas on the brain stem, but there will be an opportunity coming up pretty soon to do an editorial illustration for the Journal of Neurosurgery,” he said, grinning from ear to ear. “I’ve been drooling over the illustrations in that journal since I came to Augusta. That opportunity would be just amazing.”

According to Behr, Lawrence and Pfeiffer’s successes aren’t uncommon. More importantly, though, she said each success felt a little like a family victory.

Part of that comes from the size of each class. Pfeiffer and Lawrence’s consisted of just nine students.

“For me, as a faculty member, when you’re in a smaller environment, you get to know what’s going on with the person,” she said. “You can understand better how to relate to them about what they’re communicating in their artwork, but you can also keep an eye on how they’re doing.”

The environment, combined with the standard critique model, heavy project focus and an emphasis on postgraduation success, Behr said, ultimately separates the Augusta program from other medical illustration programs.

“It’s less of a commodity and more of a family,” she said. “The faculty really care, and the students can see that we care because we spend so much time together. You get to see how students change, and there’s common ground when you know where someone comes from on a deeper level.”

Behr would know.

In her short time as program director, she’s seen multiple students move on to weddings, engagements and new job opportunities. She’s introduced her children to her students, and the students, close as they are, refer to her frequently and lovingly as “Mama Behr.” It’s a tremendous responsibility, but also a tremendous joy.

“It’s a lot of contact time,” she stressed. “It’s not something where we can just meet with students and give them a class schedule, but we’ve found that this model allows for a lot of collaboration and growth between students. It keeps us a close-knit family, even after graduation.”

That, Behr said, is something she hopes will never change.

ONLINE EXTRA: See an archived interview with the first graduate of the Medical Illustration Program.