MCG’s Chair of Physiology has made inflammation and hypertension his life’s work.

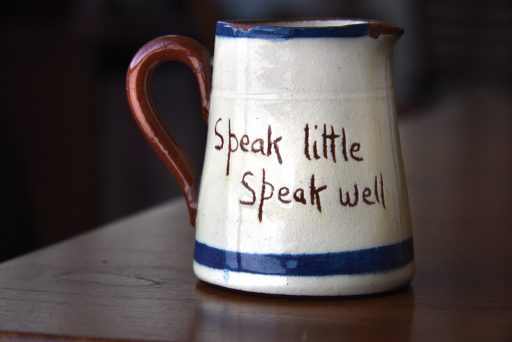

When his mother passed away in 1994, Dr. Clinton Webb gathered a few of her items that held great meaning for him from his childhood.

One of those was a creamer that Bobbie Webb always kept on the windowsill in her kitchen. “On the side of the creamer is this saying that was meaningful to her — and me: ‘Speak little, speak well,’’’ says her son.

Webb speaks little of himself, but is enthusiastic about his research and the people he works with, past and present.

In my entire career of 40 years, I’ve never seen a department where everybody had a grant, and several of them have three.

– Dr. Clinton Webb

His accolades, however, are many. He has been chair of the Department of Physiology at the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University since 1999, is the Herbert S. Kupperman Chair in Cardiovascular Disease and was named a Regents’ Professor in 2011. He is also the 2013 recipient of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research’s Irvine Page-Alva Bradley Lifetime Achievement Award for his work in the field of hypertension and for serving as a role model through service, research, teaching and training.

That work in hypertension started about four decades ago at the University of Iowa. Webb, fresh from a master’s in physiology at Southern Illinois University, entered into his doctoral studies there. He joined the lab of Dr. Ramesh Bhalla, where he studied the role of the sarcoplasmic reticulum, a particular cell structure found in muscle tissue, in regulating intracellular calcium, which can cause vessel contraction and hence hypertension. He used the experimental model of spontaneously hypertensive rats being used in a program project headed by UI’s Drs. Francois Abboud and Michael Brody.

But really, it started even earlier than that. Webb had an interest in science thanks to his geologist father and decided to be a physiology major since he’d enjoyed a class in gross anatomy. After graduating from SIU in 1971, Webb was drafted and joined the Illinois National Guard. Upon his discharge in December 1971, he found himself at loose ends, having fallen into a major that didn’t lend itself immediately to a career. He says, “Individuals with training in the discipline of physiology really have no job skills, so I took a job at a women’s clothing store as a retail clerk.”

He might still be there, says Webb with a laugh, had it not been for a fortuitous connection, the first of many in his career. Webb had completed his undergraduate senior thesis with Dr. Florence Foote, a professor in the Department of Physiology at SIU and later acting chairman. Foote called her former student to find out what he was doing. “I told her I was working as a retail clerk, and she says, ‘You can’t do that, you need to come to graduate school.’ I got lucky. I don’t know what I would have been doing if Florence hadn’t called.”

Foote, a UI graduate, also suggested to Webb that he attend her alma mater for his PhD. So back to Francois Abboud and Michael Brody: Dr. David Bohr, a professor of physiology at the University of Michigan who was already known as a pioneer in the role of vasculature in hypertension, happened to visit Iowa as part of a review group for Abboud and Brody’s program project. “[But] clearly, he was there to review the project directed by Ramesh,” says Webb. The two met, and after discussing the research, Bohr invited Webb to join his group at UM.

It was another turning point and would become the basis for Webb’s current research into the relationship between inflammation and hypertension. Webb received a fellowship grant from the American Heart Association and completed two years of postdoctoral work studying the role of the enzyme sodium-potassium ATPase in regulating intracellular calcium. He spent another year working with Dr. Paul Vanhoutte in Antwerp to study how the nervous system impacts hypertension, before returning to Ann Arbor to join the faculty in 1979.

It was during the latter part of Webb’s time at UM where a project in his lab by Dr. Joyce Richey — now an assistant dean for student affairs at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California — turned his attention to inflammation. Richey was examining blood vessels from an unusual genetic model of hypertension called the stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rat. She noticed the presence of arteritis nodosa or inflammation of the arteries. “Prior to that, I’ve always been kind of a vascular and cell signaling person,” he says. “But after I got to MCG, my research into inflammation took off.”

It was a good time to start. Nationally, the science and medical community also was taking notice of the role of inflammation, not only in heart disease but also cancer, Alzheimer’s and other diseases. TIME magazine even published a cover story on Feb. 23, 2004, with the thrilling headline, “Inflammation: The Secret Killer.”

At MCG, “the experiment that kind of started everything was the cage switch,” says Webb. Done in animal models, the experiment involves placing one male mouse into a cage and a second male mouse into another cage, then switching them. Like males of many species, the male mice don’t like being in someone else’s territory.

“Their blood pressure goes up for about 90 minutes, and the other thing that they do is that they spike a fever in that 90 minutes. And so that’s where the two came together,” says Webb. “Once we did that experiment, we realized there was not only a component that was driving blood pressure higher, but also there was an activation of a fever mechanism.

“The cage switch is fundamental to what we’re doing now. It really says that the two of them were occurring at the same time. There was an inflammatory demand, which caused fever and blood pressure elevation.”

The timing was also ideal for his chairmanship. The same year Webb was recruited, MCG began offering early retirement to its eligible faculty members. “The department went from 17 faculty members to just four in two years,” he says.

“This was really a once-in-a-lifetime kind of thing. Not very many people get to build a department. It was an opportunity that you couldn’t turn down as far as I was concerned.”

Webb made a number of key recruits. At the same time, the National Institutes of Health was in the midst of an effort to double its budget to a whopping $27.3 billion. “It couldn’t have been a better time to start a department,” says Webb. “Now it’s really tough” — due to a relatively stagnant NIH budget and potential cuts down the road.

Tough or not, today every one of Webb’s 14 faculty members holds an extramural grant in the fields of cardiovascular, endocrine or neuroscience, with a total of $7 million in funding annually. “In my entire career of 40 years, I’ve never seen a department where everybody had a grant, and several of them have three.”

Another major goal was to get into the top-50 medical school physiology departments as ranked by the Association of Chairs of Departments of Physiology; MCG’s has held steady at about 25 for the last 10 to 15 years. “I pinch myself every morning,” says Webb. When asked what he thinks has led to this success, Webb says with a laugh, “Luck? It just really came together. We’ve done really well.”

Webb at a Glance

EDUCATION/EXPERTISE

• Alumnus of Southern Illinois University, with a BA in Physiology n PhD at the University of Iowa

• Postdoctoral studies in the Department of Physiology, University of Michigan, and the Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, University of Antwerp n Professor, Department of Physiology, University of Michigan n Fellow and former chair of the American Heart Association’s Council for High Blood Pressure Research

ACCOLADES

• Recipient of the American Heart Association Council on High Blood Pressure Research’s Irvine Page-Alva Bradley Lifetime Achievement Award

• Inaugural recipient of the Bodil M. Schmidt-Nielsen Distinguished Mentor and Scientist Award from the American Physiological Society’s Women in Physiology Committee

• Recipient of the Carl J. Wiggers Award from the Cardiovascular Section of the American Physiological Society

• Recipient of the AstraZeneca Award from the International Society of Hypertension n Member of the American Physiological Society, the American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, the International Society of Hypertension and the American Society of Hypertension[/su_note]

Dr. Clinton Webb knows inflammation and the damage it can cause firsthand. He’s the child of two smokers, and his wife, Nancy, an early childhood education and childhood development specialist at Augusta University, had a father who smoked. In 1984, after the death of Nancy’s father at age 72 from smoking-related causes, Webb was motivated to change his own life and his own health. Like his parents before him, he was a smoker, and a sedentary lifestyle had led to weight gain. On that day, Nancy was with her family, and Webb put daughter Rachel in charge of her younger sister Ashley. He bought a pair of running shoes and, just like that, went for a run. That first run was only about two blocks, but it marked the start of a true lifestyle change. Webb stopped smoking, focused on a healthier diet and has become an avid runner since, having competed in seven marathons all across the United States. “Now my goal is the same every year; I run 2,000 miles a year.”