There is a nearly 20-year-old drug that can significantly improve the lives of sickle cell patients; still, most patients don’t adhere. Researchers at the Sickle Cell Center want to change that paradigm.

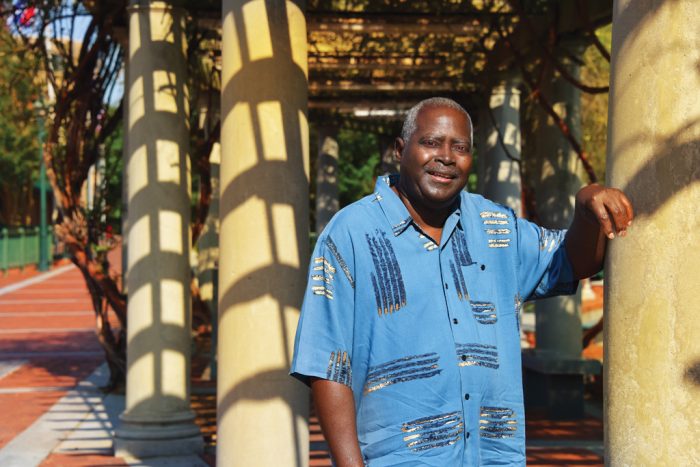

He was told he wouldn’t see his eighth birthday, so when Cecil Gresham Jr. turned 7, he started counting down his months. He was told he wouldn’t see his eighth birthday, so when Cecil Gresham Jr. turned 7, he started counting down his months.

He didn’t really understand why he might die, even had the fleeting thought that he might be cursed. “All I knew was I just kept getting sick,” says the now 60-year-old.

The pain might start in his knees or back, in the background at first like a toothache before the gum begins to throb. What the pain would become is more like laying your hand out flat then hitting it with a ball-peen hammer used in metalwork, he says. Pain crises regularly rocked Gresham’s early life. The unrelenting pain might last for days, the subsequent soreness and weakness days more.

He was diagnosed with sickle cell disease at age 2 and a half when his mother sought medical advice on why her son just would not stop crying.

It was a comparatively bleak time for his genetic disease, in which the bone marrow produces short-lived, red blood cells that don’t carry oxygen well. They turn an odd, inflexible sickle-shape when they release what little they do carry. The now-rigid cells smack into blood vessel walls as they travel – injuring the wall, producing scar tissue, then sometimes clumping together, further blocking flow through that vessel like a bad freeway pileup.

There were no drugs then that could alter the disease course, only ones to temporarily diminish Gresham’s pain. One of six children in his Augusta family and the only sibling with full-blown disease, he remembers sitting on the porch watching friends play and how even a cool day could set off a pain crisis, unless he was well dressed and hydrated and didn’t overexert. When he reached his early 30s, Dr. Paul F. Milner, his doctor who directed the Sickle Cell Center at the Medical College of Georgia, told him about a drug they were studying that held promise but, of course, had side effects, and Milner patiently explained them all.

Gresham, weary of the constant pain, enrolled in a study of the chemotherapy agent hydroxyurea. In addition to its power against cancer, scientists found hydroxyurea could turn up the production of fetal hemoglobin, which cannot assume the damaging sickled shape.

The drug has now been approved for nearly two decades. It’s recommended as a lifelong therapy starting as early as age 9 months for most patients, but Gresham, who still takes it every day as prescribed, again finds himself in a minority that is hard to explain. A 2015 report in the New England Journal of Medicine indicated that less than a quarter of the patients who should take the drug actually do.

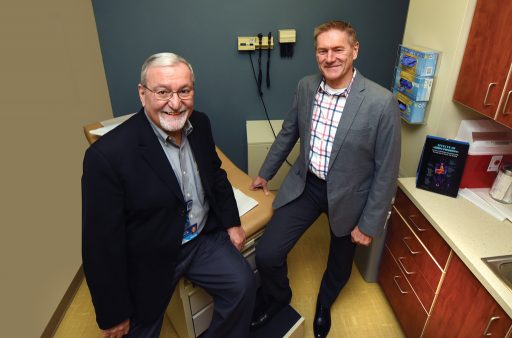

“Sickle cell disease is a chronic disease, and what is most devastating for the patient is end-organ failure from the multiple crises and from the sickling,” says Dr. Robert W. Gibson, a medical anthropologist and director of research for the MCG Department of Emergency Medicine and Hospitalists Services.

”But when you are 20, you are not necessarily anticipating protecting yourself from things that you cannot know and feel. In other words, you need to be working to keep your circulatory system as healthy as possible, to keep inflammation down, to keep as many healthy cells traveling through your circulatory system. That reduces later problems with the heart and with the liver and kidneys and all those other things. Taking hydroxyurea does that,” he says flatly.

“Like Robert was saying, that’s part of the issue, at least with therapies that can stretch across a lifetime,” says Dr. Abdullah Kutlar, hematologist in the MCG Department of Medicine, who has directed the Sickle Cell Center since 1994. “It’s very hard to argue with a teenager who is feeling great, to say you have to take this medicine every day for the rest of your life to prevent your organs from failing 30 years from now.”

“It’s probably not much different from why people don’t take their blood pressure medicine or insulin or heart medicine,” Gibson adds. “People at some level resist the regulation of medicine and don’t connect the taking of it today with health tomorrow.”

“I forgot” is the most common reason Kutlar hears, particularly from those young patients. Some will take it for a year, say they see no difference and stop. Kutlar has had many patients tell him that they just “feel bad” taking the drug. The fact that it’s a chemotherapy drug even raises the specter of cancer for some. And there are side effects. Some are obvious like hair loss and nausea. Some patients gain weight, but rather than the drug causing much of that directly, it’s at least in part because a body with active sickle cell disease is burning a lot of calories just making blood cells. The drug lowers the white blood cell count, which raises infection risk. The bottom line is that even at the well-established center at MCG, only about 35 percent of patients take the drug as prescribed, while closer to 100 percent could clearly benefit, says Kutlar, who admits frustration with but not acceptance of the poor percentages.

“A question both the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are focusing on is why, after 20 years, when we have such an excellent drug that makes a big impact on the disease, it is not used very commonly,” Kutlar says.

He and Gibson are leading a six-year, $4.4 million grant as part of the NIH’s Sickle Cell Disease Implementation Consortium to figure out the whys and what to do about hydroxyurea use specifically. They also are exploring the larger issue of how to ensure overall evidence-based care is provided to patients like Gresham who now live well past age 8.

Science is Slow and Implementing Findings Can be Slower

“That is where implementation science is born and it’s looking at why it’s taking so long,” Gibson says.

For a variety of reasons, it generally takes about 17 years for new treatment strategies for pretty much any disease to take hold in common clinical practice. With hydroxyurea, that holds despite two decades of experience with it – and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute’s Evidence-Based Management of Sickle Cell Disease Expert Panel Report in 2014 that essentially recommends it for all patients from the age of 9 months. Earlier usage recommendations were for patients with severe disease. “The thing is, it’s now seen as highly preventive,” Gibson says.

And the conundrum includes more than the drug.

Because even the “Quick Guide” of Evidence-Based Management for these patients is long. The report covers every-thing from stroke to acute chest syndrome to pulmonary hypertension to kidney failure to an unnaturally prolonged erection. It covers how to help patients avoid problems like pneumonia and how patients need to seek immediate medical attention with a fever of 101.3 degrees as well as recommendations for reproductive counseling. It covers how to identify children at high risk for stroke, with an annual screening with painless transcranial Doppler, a method identified by MCG researchers Drs. Robert Adams and Virgil C. McKie in the early 1990s.

It also covers how regular blood transfusions – also sometimes used for pain crisis management – dramatically reduce a high-risk child’s stroke risk, another MCG-led discovery. It makes clear how this condition, which affects the blood, essentially affects the entire body.

It Takes a Neighborhood

It also tells MCG researchers that in addition to dissecting hydroxyurea usage, they also need to shore up medical homes and expand them into neighborhoods.

“It’s a chronic illness that requires multiple specialties and uses health care across the continuum of care, and historically both children and adults have received the majority of their care from specialists,” Gibson says.

Increased longevity in sickle cell means patients not only need specialty care for a longer period of time, but also good, preventive primary care – from mammograms to prostate exams and cholesterol checks. Some emergency room visits are almost inevitable so these providers also need to be in the medical neighborhood they plan to build. Established neighborhoods will help ensure that everyone involved in a patient’s care, knows the essentials and who is responsible for them.

Medical homes, which are springing up in many medical professions, were a focal point of a multiyear NIH grant to Kutlar, Gibson and other colleagues in 2009. They began to establish educational programs for practicing family medicine physicians and residents in Georgia that would better prepare them for the pervasive impact of sickle cell disease and the diverse and sometimes relentless needs of patients. Dr. Richard Lottenberg – now retired from the University of Florida College of Medicine, a hematologist and expert in health services, who previously directed the Sickle Cell Program there – helped with that earlier work and will now help grow medical neighborhoods.

They are getting insight from specialists, primary care providers, emergency departments and patient communities in their quest to enable best practices for patients, whether they live in proximity to a sickle cell center or in a more rural environ. Again, it’s no small task. For chronic pain alone, there is a 12-point checklist of basics such as using long- and short-acting opioids for pain when non-opioids don’t work, annual pain assessments and a single physician writing prescriptions for the long-term opioids.

Like most neighborhoods, each medical neighborhood will have a fairly unique feel and function. “One size definitely does not fit all and we learned that by experience,” Kutlar says.

But whatever the final configuration, communication, collaboration and patient contribution are critical to the neighborhoods and will help bring to immediate light a concerning trend for an individual patient like a lot of emergency room visits or not taking his medication. Ideally, they will help avoid these negative trends.

“In a neighborhood, we would develop the collaborations so that when someone shows up in the emergency department, their primary care and specialty care records are available, even when it’s a different electronic health record system,” Gibson says. “The neighborhood is a way of communicating. When they exist, it’s then about changing provider and patient behaviors. Right now, a lot of patient info is self-reported. Treatment is episodic, disconnected, and that does not lead to good health.”

Even patients like Gresham, who has had a medical home at the Sickle Cell Center most of his life, have been questioned and suspicioned. He has been called a drug seeker. He remembers an emergency department visit when he was asked whether he even had sickle cell disease then being apologized to when the lab results came back showing that indeed he does. He appreciated the apology but not waiting in pain for the lab results. That’s part of why he goes with Kutlar to teach medical students: “I want students to believe when they see a sickle cell patient. You don’t label them and say they are drug seekers or they are putting on.”

Implementation Help from Texas

“It’s a sad situation when there is treatment available that can reduce pain and suffering and extend life and it’s not being used to its full potential,” said Dr. Maria Fernandez, director of the Center for Health Promotion and Prevention Research at the University of Texas-Houston School of Public Health. Her focus is cancer, and she is now immersing herself in the complexities of sickle cell disease so she can help the MCG team design strategies for getting the information on what stands in the way of best practice guidelines being used as well as an implementation strategy that will better get that job done.

“We don’t just want to understand the problem. We want to be able to understand what are the barriers and facilitators for establishing this kind of communication, for getting people that kind of access and how we can intervene,” Fernandez says.

Aging with Style and Purpose

At one time, Gresham likely considered aging the least of his problems.

Milner promised him long ago, that while hydroxyurea was not a cure, it should be a path to a better life. As he looks back, Gresham finds himself, like most of us, aware of the imperfections but feeling blessed just the same.

Gresham never married or had children, because he was concerned about passing along the disease. “That would tear me up on the inside,” he says in his calm, methodical style.

He really wanted to go to college, but was sick too much in those early days. His goal to be an automotive technician also was thwarted, first because he missed so much school and later because his sickle cell disease made the work environment too challenging.

He knows with certainty that cold days are his toughest and that he must adhere to flu-response strategies of dressing super warmly and consuming lots of fluids in the winter. He has his own best practices for pain control. When the familiar feeling starts, he takes a Percocet. If he is still hurting 30 minutes later, he takes another. In another 30 minutes, he knows it’s time to head back to the Emergency Department.

But hydroxyurea dramatically reduced his pain crises and Emergency Department visits and helped him finally fill out his 5’11” frame. Like the MCG researchers, he encourages others to take it and to give it to their children. Still the disease has enlarged his heart and contributed to shoulder and hip problems.

Gresham has tried much of his adult life to sustain a support group for patients like himself with this relatively rare and pernicious disease. He found mostly that other people with it prefer not to share their concerns; others who don’t have it stand back when they hear that you do.

But Gresham stuck with the support group until this year, primarily for the children, who need to know that chances are outstanding they will see well beyond their eighth birthday.

THE NUMBERS

Some 70,000 to 100,000 Americans have sickle cell disease, according to the American Society of Hematology. It affects people of African descent, Hispanic-Americans from Central and South America and people of Middle Eastern, Asian, Indian and Mediterranean descent.

THE GRANT

MCG is among eight centers nationally comprising the NIH’s Sickle Cell Disease Implementation Consortium. Each center has a strategic focus, but as with the growing neighborhoods, there also is a lot of conversation among the centers with a common interest in sickle cell disease. Unlike many NIH grants, this one is less about finding and more about implementing. MCG is among eight centers nationally comprising the NIH’s Sickle Cell Disease Implementation Consortium. Each center has a strategic focus, but as with the growing neighborhoods, there also is a lot of conversation among the centers with a common interest in sickle cell disease. Unlike many NIH grants, this one is less about finding and more about implementing. “We are actually developing methods to implement the national guidelines, which are now several years old,” Dr. Robert W. Gibson says. “It’s not, for example, to prove if hydroxyurea is effective; it’s to look for methods and ways that we can get providers to prescribe it and patients to take it, ways to help people understand that this is a relevant and meaningful treatment for their disease.” Each center also is helping to populate a Sickle Cell Disease Registry that provides demographics, disease types and lab and clinical histories on about 300 patients, which will be a natural for population-based sickle cell research of the future and help document treatments, outcomes and the life course of the disease, Gibson says.

THE TREATMENTS

Studies of all three of the major treatment/prevention strategies for sickle cell disease were halted early because of overwhelming evidence that they worked. This includes giving penicillin as well as the pneumonia vaccine to newborns diagnosed with sickle cell disease. The poorly functioning spleen of these babies left them vulnerable for infections like the bacteria that cause pneumonia. Together the two standards of care resulted in one of the biggest improvements in patient survival, Kutlar says. MCG, first under the leadership of Dr. Paul F. Milner and then Dr. Abdullah Kutlar, was a study site for the original hydroxyurea studies. Adults taking the once-daily drug had pain crises and hospitalizations nearly cut in half. Subsequent studies in children, dubbed BABY HUG, showed that even children who were asymptomatic when they enrolled in the studies had fewer problems, and those who already had symptoms had fewer pain crises, less acute chest syndrome – where blood vessels in the lungs clamp down – and less dactylitis, painful inflammation of the toes or fingers known as “sausage digits.” The preponderance of evidence led to the Expert Panel consensus that all patients and their families be educated about the drugs along with strong recommendations that the drug be used as prescribed to essentially all patients ages 9 months and older, regardless of how their disease has presented. Exceptions include discontinuing the drug during pregnancy and a weak recommendation for patients with chronic kidney disease already taking erythropoietin, a hormone produced by the kidney that increases red blood cell production, which is also increased by hydroxyurea. While some would suggest that as many as 30 percent of patients don’t respond to hydroxyurea, Kutlar’s work has put it closer to 9 percent of patients who seem to be taking it as they should without the expected positive results. The NIH-funded STOP studies, led by MCG researchers, first identified painless transcranial Doppler as a way to identify children with sickle cell at high risk for stroke and then showed that regular monthly blood transfusions could cut the risk by 90 percent.

THE REALITIES

When Dr. Abdullah Kutlar, director of the Sickle Cell Center for more than two decades, frequents national gatherings on his chosen specialty, he counts himself among a seriously aging group of physicians. He calls himself and fellow adult hematologists who chose to focus on sickle cell disease an “endangered species.” In the collective 10 years that he directed the hematology/oncology fellowship training program at MCG and AU Health, for example, only one fellow chose to follow in these dwindling footsteps. Just don’t label sickle cell a “benign’” disease. “When you see these patients, when you witness what they go through, what complications they can potentially develop, you don’t use that word for sickle cell disease,” he says. “We know what is wrong: It’s a mutation in the human hemoglobin.” But it affects literally every organ system, from strokes in the brain to jaundiced eyes to acute chest syndrome to painful, constant penile erections. Some mechanisms are definitely known; still plenty of dots need connecting, he says.

THE REACH

Adult outreach sickle cell clinics were started by Kutlar’s predecessor, Dr. Paul F. Milner, in the 1990s. Dr. Virgil McKie, retired pediatric hematologist/oncologist, started the decade before. Today the adult clinics are in Albany, Macon, Savannah and Sylvester, Georgia, and pediatric clinics are in Albany, Dublin, Valdosta and Waycross. All told, about 1,500 adult and pediatric patients across Georgia receive care from MCG faculty.

THE WATCH

Pain crises are responsible for about 90 percent of hospitalizations, and emergency departments are where many patients have their worst experiences. Observation units, which take patients out of the usual busy fray of an emergency room so they can get more prompt pain crisis attention, also reduce the chance they’ll be labeled a drug seeker, someone who just seems to know too much about which and how much opiate he needs. Dr. Matthew L. Lyon (’99), vice chairman of academic and research programs in the MCG Department of Emergency Medicine and Hospitalists Services, helped establish the sickle cell path in the observation unit in AU Health’s adult Emergency Department nearly a decade ago. He has since helped Phoebe Putney in Albany and Memorial University Medical Center in Savannah, an affiliate of Mercer University School of Medicine, establish similar pathways. If the new implementation grant goes as planned, patients will be spending even less time in emergency rooms, Kutlar says.