MCG researchers discovered nearly 20 years ago that tumors and fetuses use the enzyme IDO to escape the immune response. A drug that blocks that pathway is now helping children with relapsed brain cancer.

Hen Smadga did not want to believe it.

But the MRI, taken at Chaim Sheba Medical Center at Tel Hashomer, Israel, could not be denied: A growth was there at the base of her son Eliya’s skull, a tiny mass with a long name – medulloblastoma.

In a way, medulloblastoma could be considered among the rarer of pediatric brain tumors, accounting, as it does, for only about 18 percent of all tumors that occur in children. But at the same time, the embryonal tumor, which always starts at the cerebellum, is the most common malignant brain tumor in children—tending to grow rapidly and then spread to other parts of the brain and spinal cord.

For Smadga, it was as though the tumor arrived overnight: One day, her six-year-old son Eliya was laughing and playing, the next he awoke with his head pulled over to one side, staggering “like a drunk man,” says Smadga in her soft, lilting Israeli accent.

Life in their hometown of Gan Yavne, a bustling city in the heart of Israel, would never be the same. The next year was a blur: surgery, then a month and a half in the pediatric intensive care unit, followed by more time on the oncology unit, and finally six rounds of chemotherapy.

After that, “everything was perfect,” says Smadga. Eliya was back at school, playing and teasing his sister. Until he woke up again with the same staggering walk.

The cancer was back, and this time doctors prescribed 30 rounds of radiation directed at Eliya’s brain and along the spinal cord. The tumor responded, but then it adapted. It took only a month for it to rebound.

“The doctors told me, there is nothing more to do,” says Smadga.

“I said, ‘I can’t live with this, there has to be something to do, somewhere. He feels well, he looks great, he walks, he talks. This can’t be the end.’ I started to search for something in the world.”

Putting the Pieces Together

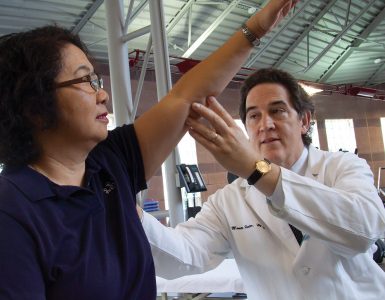

More than 6,000 miles away in his office in the Bert M. Storey Cancer Research Building on the main campus of the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, Dr. Ted Johnson was looking at his schedule. Among the colored blocks outlining his day, his finger traced those that were part of a research project that he has been involved in ever since he was an MD/PhD student in the Class of 2004 at MCG.

Like breast cancer, pediatric cancer is a topic that gets plenty of airtime. But unlike the adult cancer, pediatric cancer research is woefully underfunded. “It’s economics,” says Johnson bluntly. “Kids are always behind adults because there are so many fewer cancers in kids…I don’t pretend to understand the business part of that.” It’s estimated that childhood cancer accounts for less than one percent of all cancers – roughly 10,300 new cases in 2016 versus 1.6 million new cases of cancer overall, according to the American Cancer Society.

Among pediatric cancers, brain cancer is especially underserved since children with the disease can be too fragile for any type of aggressive therapy. “But we thought it was a population that needed options and that if we built the capability, people would come here to get it. There wasn’t any guarantee, but the promise was there.”

The “we” is Johnson and fellow pediatric oncologist and immunologist Dr. David Munn (’84) who together with immunologist Dr. Andrew Mellor, were Johnson’s mentors while he was a student. It was Munn and Mellor who in 1998 discovered an important link between cancer and the enzyme IDO, which is one way that the mother’s body protects a fetus from being attacked by the immune system during pregnancy: Tumors also use IDO as a shield.

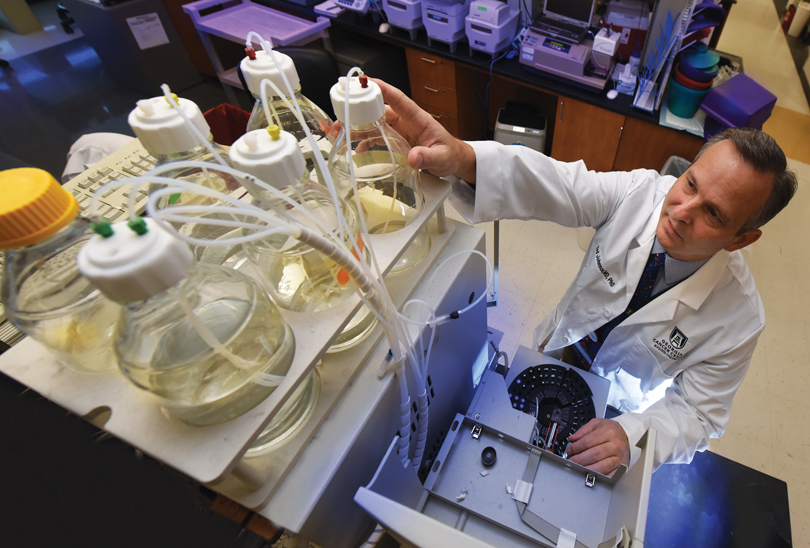

Munn and Mellor helped develop a drug that blocks the IDO pathway, and Johnson was recruited back to MCG after completing a clinical fellowship in pediatric oncology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital to continue that work.

Johnson had talked and thought about the many ramifications of the research ever since he was a graduate student. Numerous pathways exist for application of the drug called Indoximod, but thanks to their background in pediatrics, Munn as well as Johnson felt it was a priority to move it and other experimental immunotherapy drugs into treatment for children.

That was in 2010. Even at a large center like Cincinnati, during Johnson’s time, no pediatric immunotherapy program existed. He and Munn slowly put the pieces together in order to launch such a program at MCG and the Children’s Hospital of Georgia, including a pediatric clinical trial specifically for children with brain cancer using Indoximod. The first step was to prove in a lab setting that combining the drug with chemotherapy and radiation was safe and could have beneficial effects on brain cancer. But it was a period of lean federal funding for any research lab, much less one focused on an area that historically has been underfunded.

That’s when Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation helped fill in some missing pieces.

In 2014, the foundation awarded Johnson’s research with an “A” Award Grant of $375,000 over three years, marking its first-ever gift to the university. “This one stood out from all of the ones that we received as being potentially impactful to kids with cancer,” Jay Scott, co-executive director of the foundation, said at the time in an interview with The Augusta Chronicle. “One of the things we like to do with our grants is [ask], could this project impact a kid with cancer within five years? If we can answer yes to this, then we really like the projects even more.”

“It was not our first major grant [Hyundai Hope on Wheels had awarded Johnson a $100,000 grant back in 2011 and then another $250,000 grant in 2016], but it was very important to funding the preclinical data necessary to justify the clinical trial and show the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the drug company that this drug was something that we should look at in pediatric brain tumor patients,” Johnson says. “At the time we started writing the clinical trial, no one was using the entire class of IDO inhibitors for brain tumor patients at all, and not any children.”

One year later, Alex’s Lemonade Stand returned, this time to select Johnson as one of only three inaugural recipients of the foundation’s Bio-therapeutics Impact Grants with $840,000 in grant funds to launch the pediatric immunotherapy trial. “We had everything ready to go, but the last hurdle was getting grant funding to get started,” Johnson says. “Honestly, their grant was pivotal to showing the drug company that we had the support of the field of pediatric oncology. That was a big part of us getting the trial launched, as it underwent peer review for the grant award process.” The drug company, NewLink Genetics, would provide partial funding for the clinical trial as well, while an anonymous donor was also critical in both the preclinical and clinical funding with gifts totaling more than $2 million.

Then, another connection: In early 2015, the board of directors of the Cannonball Kids’ cancer Foundation (the lowercase “c” is deliberate to give the word “ cancer” an inferior status) met with several CEOs of established nonprofit organizations dedicated to childhood cancer for insight as to where its research funding would have maximum impact. When the board met with Scott and his wife, Liz, co-executive directors of Alex’s Lemonade Stand, Johnson’s work resonated.

“We knew this was our guy. Dr. Johnson is going to make a footprint in pediatric immunotherapy, and we are going to help him help kids around the world,” said CKc co-founder Michael Wiggins.

Cannonball Kids’ has since awarded two $100,000 grants to Johnson and Munn, with the most recent gift supporting the hire of a new pediatric nurse practitioner and helping to expand the trial. Alex’s Lemonade Stand has also matched donations by a team of Johnson’s supporters to give another $53,000 in unrestricted funds during Alex’s Million Mile event. Most recently, two area foundations—Augusta’s Press On Fund and Aiken, South Carolina’s CAM FUND, both launched by families with children impacted by brain tumors — joined forces to grant another $150,000 to the Indoximod trial for pediatric brain cancer.

The Work

To date, MCG remains the lead site in a two-hospital consortium offering the only pediatric cancer clinical trial in the world using Indoximod in children with relapsed brain cancer.

Fifty-four slots were available when the trial opened and thanks to continuing grant support, the available slots have doubled. Johnson’s team has recently extended the trial to include children with newly diagnosed diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma or DIPG, a fast-growing and difficult-to-treat cancer that invades the brain stem with a grim prognosis: Only about 10 to 20 percent of children are alive at 12 months after diagnosis.

The promise of the work is such that it is hard sometimes for those outside of it to remember that the trial is in fact caring for children who are quite ill. “All of the kids who come to us have very advanced brain cancer,” Johnson says. “There are all different types and patterns of brain cancer, but what’s true is that all have failed to respond to standard treatment. And the world doesn’t have second treatments for brain tumors.”

Since the trial opened in 2015, several patients have passed away – a fact that strikes Johnson forcefully as a father to three young children himself. Then there are patients like Eliya: Since arriving in the States in August with his mother, his father Yossi, and sister Abigail, he has followed the protocol set by the trial, a combination of Indoximod and moderate chemotherapy. Every two weeks, he has follow-up visits at the pediatric cancer clinic at the Children’s Hospital of Georgia, and every two months he undergoes an MRI.

And he is remarkably well, looking and acting like any child without cancer. “He’s been great, he feels well,” says Smadga, who found Johnson by chance during an online search. She and Eliya’s doctor spoke to him by phone for hours before making the decision to move the entire family to Augusta so Eliya could be part of the trial for a year. Within a month, they were here. “The treatment, we think it’s working.”

To not just save life, but to make that life worthwhile for a child with cancer – filled with memories of birthdays and laughter and family – has always been Johnson’s hope. “The idea that we could slow down the cancer they have and help them enjoy a little bit more of life was really powerful.” It’s also a fact that Johnson can now talk about, with initial trial results reported during a presentation at the 22nd Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuro-Oncology in mid-November.

“Some patients who received chemotherapy with Indoximod did better than we would have expected based on the aggressive nature of their relapsed, often metastatic brain cancer,” Johnson says. “Almost all of these children had been previously treated with radiation, making it difficult to give additional radiation treatments. However, patients who were able to receive additional radiation with their Indoximod therapy fared even better, and importantly they did not have to receive radiation at the standard, highest dose in order to show benefit when combined with the immunotherapy.

“This makes us hopeful that, in future combination immunotherapy treatments, we may be able to provide benefit to these children while reducing side effects by using lower doses of radiation and/or chemotherapy.”

Even today, a search on ClinicalTrials.gov for pediatric brain cancer pulls up only 115 clinical trials. When adding the search term, immunotherapy, that number drops to four. And of those four, only two – including MCG’s – are currently recruiting.

“I had a chance to stay in Cincinnati — I had a job lined up in the bone marrow transplant section when David Munn called me,” Johnson says. “It didn’t take David long to convince me that we could do this…The brass ring was that we could potentially offer this treatment to kids who otherwise would have to wait 10 years for a drug to be approved. It was very, very appealing. I can’t describe it. It drives you forward.”

For Supporters and Families

The Medical College of Georgia is conducting a fundraising campaign to help significantly increase the number of children who could have access to this trial. To learn more, contact Eileen Brandon at 706-825-4779 or ebrandon@augusta.edu. To learn about enrolling in the trial, contact Robin Dobbins, RN, at 706-721-2154.