A new one-year fellowship in forensic pathology aims to address the critical shortage in this field.

The newest fellowship program at the Medical College of Georgia is designed to train more of the physicians who investigate unexplained and unexpected deaths. A one-year program, the Forensic Pathology fellowship is the newest of only 40 accredited training programs in the country and is sponsored by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation.

According to the National Commission on Forensic Science, a commission formed by the U.S. Justice Department in 2013, there are approximately 500 practicing board-certified forensic pathologists in the country, less than half the number needed.

“Over the next few years, the nation will be losing even more qualified forensic pathologists, mostly as a result of retirement,” says Dr. Stacey Desamours, associate medical examiner and director of educational programs at the GBI Headquarters in Atlanta. “The accredited training programs will produce at most 40 new board-certified forensic pathologists per year. In essence, there are simply not enough newly graduated forensic pathologists to meet the current or future needs of the United States, let alone the state of Georgia.”

In Augusta, for example, the medical examiner’s office has been empty for almost three years. Bodies have to be sent to the State Crime Lab in Atlanta for autopsies, says Dr. Amyn Rojiani, Edgar R. Pund Distinguished Professor and chair of the MCG Department of Pathology. “That is one of the driving forces of us initiating this fellowship. Irrespective of where they come from, individuals will typically end up practicing in areas where they complete their residency and fellowship. It is our hope that if we get these people here, to train in our program, and we eventually offer them a position, they’re more likely to stay.”

In Georgia, there are 25 full-time forensic pathologists – 15 employed by the GBI (11 at the Atlanta headquarters, two in Macon and two in Savannah); four at the Fulton County Medical Examiner’s Office; two in Dekalb County; one in Gwinnett; and three in Cobb County. As a general rule, there should be one per 200,000 population, Desamours says. “Based on Georgia’s population of nearly 10 million, we need 45 to 50 full-time forensic pathologists working in the state.”

Shortages can lead to backlogs in court cases and insurance claims, not to mention longer waits for families to get closure following the death of a loved one, Rojiani says.

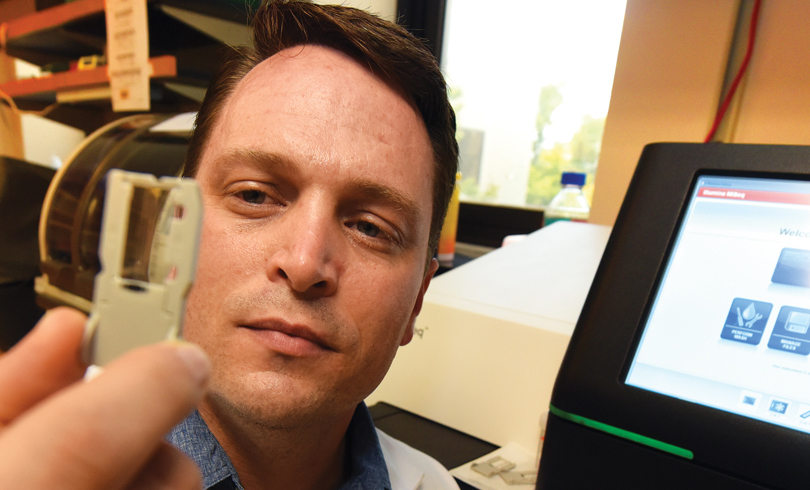

The new MCG fellowship will accept its first trainee in July. The program will include hands-on training in autopsies, toxicology testing methods, reviewing crime scenes and using the latest in molecular techniques like DNA testing. Fellows will also train at the GBI Headquarters Crime Lab in Atlanta, where there’s a diverse caseload and in-house experts in toxicology, firearms, trace evidence, blood serum and crime scene investigation, Desamours says.

The program will also address the administrative aspects of the job, like how to put together death reports and how to testify in court, and there will be a requirement that trainees conduct research that contributes to current literature, Rojiani says.

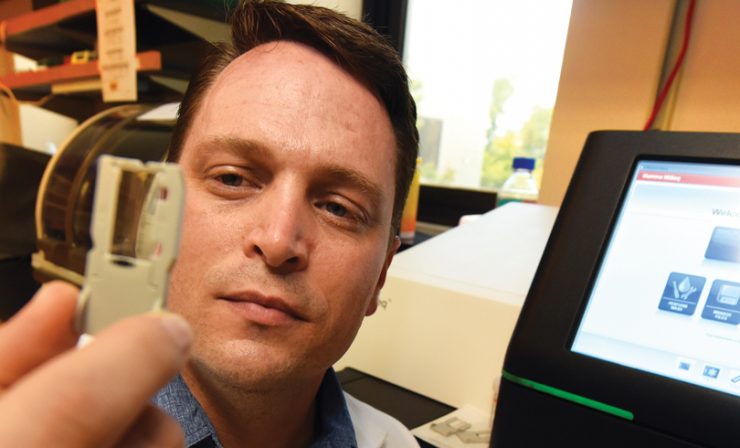

The program will be co-directed by Desamours and Dr. Joseph White, an assistant professor in the MCG Department of Pathology who recently completed a surgical pathology fellowship after spending five years as an assistant medical examiner in Salt Lake City.

White himself admits that the profession is faced with a myriad of challenges — perhaps chief among them is attracting pathologists to the subspecialty’s lower pay. Pathologists in private practice may make almost twice as much as the typical medical examiner, who is usually a county or state government employee.

“Almost all of the pathology fellowships give you an ability to have an area of specialty while still practicing in the general field of surgical pathology,” he says. “Forensics is very different. It’s often a one-way door into just doing forensics. It can be difficult to convince people to spend an extra year of their life for training for the opportunity to do a job that pays less than you would make otherwise.”

“You truly have to be committed, motivated and have the mindset to take this on,” Rojiani adds.

But there are definite rewards to the profession. “As someone who has done it for many years, you realize you have an opportunity to do a lot of important things,” White says. “When you’re asked to reconstruct and rebuild the final moments of a family member’s life, that’s important to everyone.

“You’re also able to impact the community in a different way. Just the things that have changed, even in my lifetime — the spacing distance between the bars of cribs, for example. They’re standardized because medical examiners identified that as a danger. Because of medical examiners’ findings, today every five-gallon bucket in this country has a picture of a baby falling into it. That’s a different way of interacting with society, something that you don’t feel as much in the typical hospital setting.”