Ron Booth knows that big enterprises are built on little things, and as vice president for Facilities Services, many of those little things fall under his jurisdiction.

So he spends a lot of time thinking about them.

A lot of time.

“Facilities is here to support the entire mission of the university,” he says. “There are subsets of that mission — teaching and research and the medical center — but the one reason we’re here is to provide support.”

And while that might be a bit of an oversimplification, not to mention exceedingly modest, the fact of the matter is, providing support means Booth and his teams operate in the background, mostly unseen. In fact, success in his world is measured largely by not being noticed. If you’re not being noticed then nothing went wrong, and in a practical sense, that’s what “providing support” often comes down to — making sure nothing goes wrong. But if something does go wrong, Facilities responds with an effective fix before too many people are affected. At a research university as large and diverse as Augusta University, providing that kind of support takes many forms.

For Booth, the tower crane at the site of the new $70 million, 125,000-square-foot College of Science and Mathematics Building being constructed on the Health Sciences Campus represents everything that lured him away from Auburn University in June 2019.

“When they put up the tower crane, that was a pivotal point for us,” Booth says. “We’re the only site in Augusta that has a tower crane. We’re very excited about the new building.”

With three floors of education and lab space and a fourth floor of shelled space for collaborative research and growth, the building is bringing a strong undergraduate research component to the already research-rich Health Sciences Campus and represents a big step forward in the university’s evolution as a comprehensive research university.

“There is so much positive growth here,” he says. “President Keel’s vision is what attracted me to come here.”

And that growth, embodied by Augusta University President Brooks A. Keel’s plan to boost enrollment to 16,000 students by 2030, relies heavily on Booth and his various teams.

“We’ve got to be ahead of that growth and enrollment because we’ve got to have the facilities in place before the students get here,” he says. “We have to stay one step ahead.”

Getting In At The Beginning

Even something as seemingly trivial as cataloging research space isn’t as easy as it seems, though all agree it is deceptively important.

“Since his arrival, he’s been working with us on the support systems for managing our space,” says Diego Vazquez, associate vice president for sponsored programs administration. “He’s overseeing a modernization push that will allow the university to utilize and allocate research space more effectively.”

From a research perspective, that helps because when the university knows exactly how space is being utilized, it can support the case for a higher overhead rate when negotiating with federal sponsors which allows the university to more accurately recover facility costs on grants.

Dr. Michael Diamond, senior vice president for research at Augusta University, oversees all research-related activities for the university, including facilitating the recruitment of new researchers. In order for recruitment to be successful, Diamond insists that Facilities should be a part of the discussion from the start.

Having Facilities involved at the beginning of a researcher’s recruitment allows for a smooth transition once they arrive on campus and reduces the amount of problems that need to be addressed down the line, where it can become inconvenient, disruptive and costly.

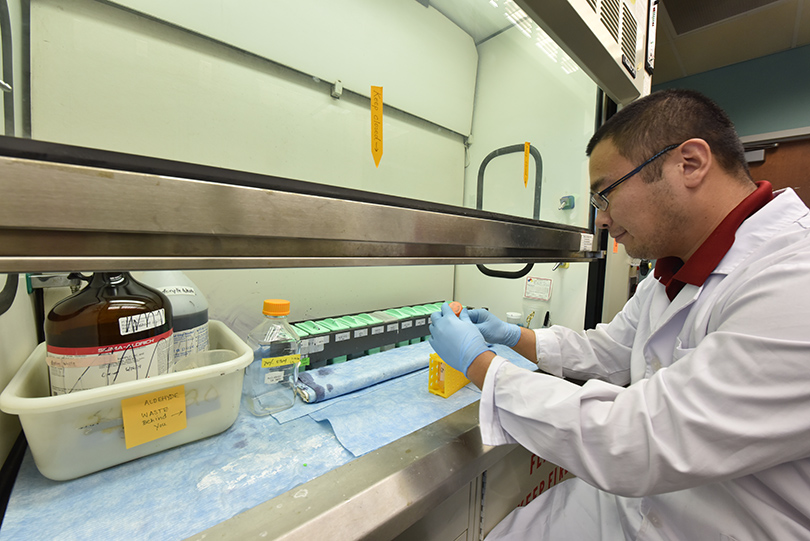

“When we’re recruiting new faculty members and they come in and have specific requirements for their labs, we have a team in Ron’s area that works with them to ensure the space is appropriate for the research they’re going to be undertaking,” Diamond says.

It’s not a courtesy, he says, but a necessity.

Booth agrees.

“We want to be involved in that process so that we understand what their needs are going to be,” Booth says. “We’ll ask specific questions about what kind of equipment they’re bringing in, whether they’re doing any animal work, whether they’re going to need any kind of low-temperature equipment like subzero freezers or any specialized equipment. We want to be prepared from a building standpoint to provide that infrastructure to make sure that equipment works.”

It’s more than accommodating for space or equipment, however. Each building has specific power requirements, which makes it imperative to know what any new demands might be. Will they need to modify the existing system? Install a step-up or a step-down transformer?

Adjusting to the institution’s evolving needs is a constant balancing act, Booth says, because these kinds of considerations don’t just get pulled out for new faculty. Booth says it’s part of the constant, ongoing evaluation that goes hand in hand with being a major research university.

“We’re also on the front end of any grant applications so we can provide support to the research team or the principal investigator who’s applying for the grant,” he says.

That awareness helps them factor the cost of whatever renovation might be needed so it can be accounted for when costing out the project in advance of submission of the grant application.

“From Dr. Diamond’s perspective, all funded awards should have a prospectively identified and approved funding source for all required renovations,” he says.

Keeping Things Running

That commitment of support quickly expands to ongoing maintenance. Take a power outage. While an outage itself might not be preventable, the response can be prepared for so that it causes as little disruption as possible.

“If the power goes out in a building, we need to respond quickly to restore power, or if there’s an emergency generator, to make sure the generator is ready to go when needed, automatically transferring over and continuing to supply power without any interruption to lab equipment,” Booth says. “If the power goes out overnight when nobody’s here, we must be confident that the transfer switches always work properly.”

Augusta University has 26 emergency generators. Each is equipped with a transfer switch, which is an electromechanical device that senses when power is lost and then switches over to the generator.

“They’re tested once a month,” Booth says. “So we’ll go in, usually very early in the morning, and actually cut the power to allow the generator to come on and make sure the transfer switch works. We’ll run it for 15 to 30 minutes. Because it’s instantaneous, anyone in the building won’t know except for maybe a flicker of the lights.”

And no loss of power means no loss of experiments or other disruptions.

After an outage, teams go in and check equipment to make sure that the lights are on, the freezers are running and any necessary ventilation is back online.

In some buildings, it’s not as easy as simply flipping a switch and waiting for the power to come back on, however.

“Here, depending on the building, we might have to go around making sure things that were on at the time of the outage are actually shut off,” Booth says. “Because for that load to come on instantaneously might cause another outage. So, depending on the situation, we may go in and ramp back up gradually.”

Ventilation hoods can be particularly problematic, he says.

The university has 183 ventilation hoods across the Health Sciences Campus and another 38 on the Summerville Campus. They are inspected annually to make sure that no matter what position the sash is in, the velocity of the air coming into the fume hood is consistently at the appropriate rate.

“If it’s less than that number, then something needs to be adjusted with the exhaust fan, and if it’s more, that’s also a problem, because that would make it turbulent inside the fume hood,” Booth says.

In addition to the hoods, the labs themselves are required to be positive or negative, which is another reason Diamond finds it so important to include Booth and his team in early discussions with incoming researchers.

“If we’re in a lab that needs to be negative, the exhaust from that room needs to be greater than any of the rooms around it,” he says. “That means that air is actually coming into the lab through cracks and crevices rather than going out.”

Certain procedure rooms require the airflow to be out of the room, or be under a positive pressure environment for infection control, eliminating the risk of airborne pathogens entering the room.

“It’s a matter of supplying a high rate of clean (filtered) air, thereby creating a positive pressure environment in relation to adjacent spaces,” he says.

To field service calls, the institution currently has two call centers — one for the university and one for the medical center. Between them, they receive approximately 2,100 calls a month.

Booth is working toward combining the two call centers into one.

“That’s my ultimate goal,” he says. “One number, one call center for everything, whether it’s hospital or university.”

You can’t address a problem if you don’t know about it, he says, and the key to knowing about a problem is making it as easy to report as possible.

“Our big thing is providing good customer service while also being very responsive,” he says. “We have to respond very quickly, and so we have a good system of work orders and call centers where people can call in to report problems.”

Cool Air and Fire Suppression

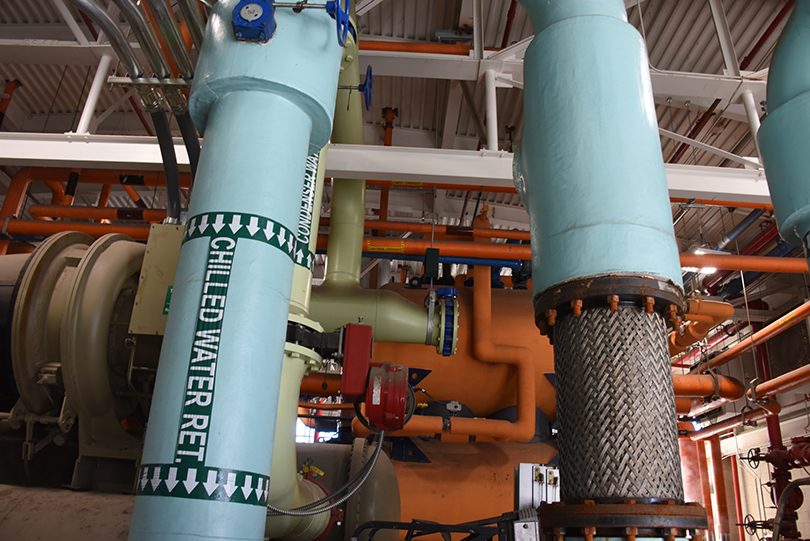

Probably the biggest system on campus — kind of the circulatory system for the entire enterprise — is the one keeping the air in the buildings cool. Approximately 10.5 miles of buried pipe run throughout campus, connecting the three power plants (two on the Health Sciences Campus and one on the Summerville Campus) with 26 chillers. Combined, the chillers handle almost 22,000 nominal tons.

A chiller manufactures chilled water at about 42 degrees Fahrenheit and pumps it into the buildings through underground pipes, where it goes through the coils in the air conditioning units, which generates the cold air. That process raises the water temperature to about 48 degrees, and that water is then pumped back to the chiller, where it’s chilled again in a constant loop.

While this is the system that keeps the buildings cool, the considerations aren’t all about comfort.

“Sometimes it’s for animals, or if they’re doing any kind of research with plants, they have really tight limits on their ambient temperatures,” Booth says. “We can generally provide that, but if that goes down, then we have to have a backup for that. If there’s plant research going on at a certain building, you need to respond in a certain way; if animals, a different way. Our job is to plan for that.”

And Plan B starts well before the problem.

“If Dr. Diamond comes in and says we need these parameters on the air conditioning, we don’t say, ‘OK, you have it — we’re done.’ We say, ‘OK, you have it — and if that doesn’t work, we have this for Plan B.’”

Keeping research space safe from fire requires yet another built-in system, and which system is used depends on the type of research being conducted and the equipment being utilized.

The university has three main types of fire suppression: water, dry chemical and gas. The water douses the fire but leaves its own damage; the dry chemical smothers the fire but requires cleanup; and the gas suffocates the fire, leaving no cleanup but a hefty bill.

“It’s very, very expensive to replace the gas, which is why they go out of their way to design the system so there are no false alarms,” Booth says. “Most of the time, if it senses a fire, it needs to have multiple locations telling it it’s a fire.”

Preparation is Key

Because Murphy’s Law states that bad things never happen when it’s convenient, Booth and his team of more than 600 people drill for any number of contingencies, the most fundamental of which involve simply accounting for everyone.

“If something happened on campus, whether it’s weather-related or some kind of other emergency, I need to know where all 600 people are within a few minutes,” he says.

So with no advance notice, Booth will send a note out to his seven directors looking for a real-time head count.

“Because in any true emergency, it’s easy to lose sight of what you have to do when keeping track of all your people,” he says. “So it’s kind of a ladder up — each individual supervisor knows where his group of technicians are, and each manager knows where all his supervisors are, and each director knows where his managers are.”

While the constant swirl of activity might seem like a three-ring circus, Booth likens it instead to what goes on behind the scenes at a stage performance.

“I kind of compare it to a live performance, where the researchers are the performers out on the stage and we’re the guys in the back, running around backstage,” he says. “We don’t get any of the glamour, but we’re helping make it a success.”