In the late 1990s, diffusion-weighted imaging was a brand-new sequence for MRI that had been found useful in locating even small areas of damage in brain tissue after possible strokes, by measuring the motion or diffusion of water in tissues. Dr. Annette Johnson, then a neuroradiology fellow at Washington University’s Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology, was part of a new project hypothesizing that this technology, which works because strokes and other conditions disrupt normal movement of water in tissues, might also be useful as a screening tool for newborns with a low Apgar score (a test at birth that measures a baby’s breathing, heart rate, muscle tone, reflexes and skin color). At that time, no tests — including conventional MRI sequences — could accurately assess possible brain damage or predict the number of babies with low Apgar scores who might go on to have developmental problems and require early intervention.

That study would go on to confirm the use of MRI diffusion-weighted imaging as a new tool offering unique insight into babies’ brains, even very early after birth. It also found that some 80% of babies with diffusion imaging abnormalities would likely have developmental problems. “Now, no one would ever scan a newborn with low Apgars and not include a diffusion sequence,” says Johnson.

Finding solutions to complex problems has always been Johnson’s bailiwick. Radiology, with its ability to peer inside the body to uncover disease and injury processes, was the natural progression.

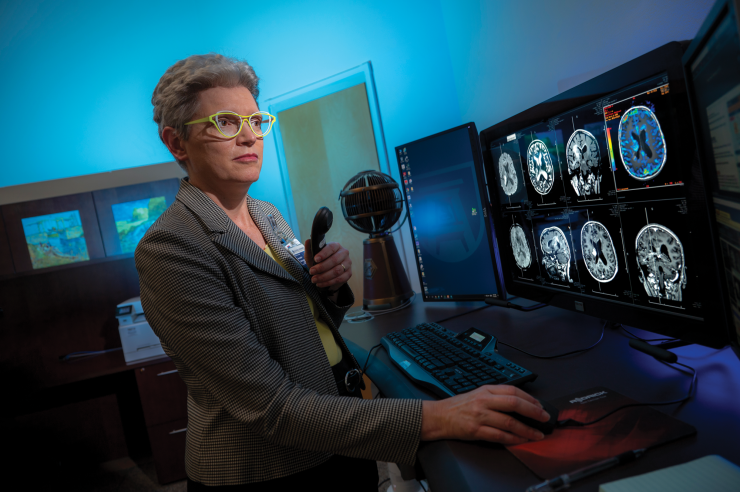

Now, since 2018, after multiple leadership roles at other institutions as well as at the national level, Johnson has been applying her skills in planning, mentoring and leading as chair of the Department of Radiology & Imaging at the Medical College of Georgia.

“I take a lot of satisfaction in solving a problem, and we have no shortage of challenges,” she says — particularly with patient volumes increasing year over year. “We are bursting at the seams… [and] I very much believe all of our research, educational and clinical goals are tied to optimizing patient care and the patient experience. That has to be our top focus.”

Beginnings

It’s the kind of joke a physician might share at a dinner party, but Johnson remembers hating seeing the doctor as a child and being “poked and prodded,” she says.

But she was always drawn to science — as well as religion. “Faith has always been very important to me. I don’t really understand why people see those as conflicting, but I’m grateful that I never did,” she says. “I think one tells us about nature, and the other tells us about meaning and purpose.”

While she’d considered majoring in physics in college, “what really sealed the deal for me was when a classmate said, ‘You can’t major in physics. Girls don’t do that.’” Her response: “Yeah, right. Watch me.”

She’d also planned to pursue a PhD in physics, until she had to undergo surgery herself during her junior year of college. From wanting to avoid the doctor as a child, she quickly “became fascinated.” “When I actually had a problem…I found that I wanted to understand as much about it as possible,” she says. “And learning more about it made it less frightening and more interesting.” She began avidly reading about medicine and even asked one of her surgeons if she could shadow him for several months, helping out in clinic and observing multiple surgeries for everything from congenital issues to trauma. “I was sold.”

At the Medical College of Virginia, her first rotation in her third year of medical school happened to be with a female neuroradiologist, Dr. Wendy Smoker, a national player who has served as president of the American Society of Head & Neck Neuroradiology, faculty for the American Institute of Radiologic Pathology, and reviewer and editor for multiple major journals. Johnson found that she liked radiology’s “big, cool toys,” its link to physics, and the problem-solving inherent in every case, but she connected particularly with Smoker. “She was formidable — a great teacher, a great leader,” she says. “She was so intelligent and so enthusiastic at teaching and really wanted every single learner around her to understand. Neuroradiology was just the most interesting thing in the world to her, and it came out of her pores.”

Another mentor was Dr. Daniel Kido, whom she worked for at Washington University during her neuroradiology fellowship, following Johnson’s diagnostic radiology residency at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pennsylvania. Kido introduced health services research to her, proving that imaging makes a real difference for patients’ lives and outcomes, which led Johnson to her second fellowship in general medical sciences to study outcomes research.

She also went on to obtain a master’s degree in clinical research at Indiana University under Kido’s guidance, and she’s done a good bit of work in outcomes research since then, including a project at Wake Forest University and its Brain Tumor Center of Excellence. In working with patients undergoing treatment for brain tumors, it can be difficult, she says, for clinicians to visualize the minute differences between the effect of treatment or the tumor continuing to grow in the brain. Given enough time, the answer is clear, but ideally, those differences would be seen as early as possible so physicians can change the treatment plan, if needed.

Johnson and the team at the brain tumor center were able to successfully determine that advanced physiologic imaging sequences — in this case, MRI perfusion imaging, using a contrast agent and rapid imaging, as well as diffusion-weighted imaging — made a difference in treatment planning. “That was very satisfying,” says Johnson, “to see that this technology is really impacting the decisions that the team is making.”

Drawn into leadership

Johnson’s extensive clinical and research work put her in a good position for leadership. But, she admits, “From early on, I had no desire to be a leader. What I wanted to do was the best possible job at whatever my job was…But when you fix something that’s broken, people will keep bringing problems to you to get solved. I was drawn into leadership; it seemed like I couldn’t avoid it.”

Just a year after completing her fellowships in St. Louis, Johnson was tapped as chief of neuro MRI in the Department of Radiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. A few years later, she was named neuroradiology division chief in the Department of Radiology at Indiana University. Then came a succession of roles at Wake Forest University, including director of workflow improvement and quality, vice chair of quality and patient experience, executive vice chair of clinical operations and interim chair, all in the Department of Radiology.

At MCG, she stepped into a role held for 17 years by former chair Dr. James Rawson — and she is a woman in a specialty that is about three-quarters male, “even though we’ve been working on that for years,” she says.

Her job, she says, is “to help [faculty members] succeed, help the staff succeed — that’s how we take the best care of patients…My job is to take care of the people who take care of the patients.”

One of her first initiatives was to reorganize the department. Facultywise, she created several vice chair positions, naming Dr. Pardeep Mittal as vice chair for clinical operations; Dr. Gilberto Sostre as vice chair for education; Dr. Norm Thomson as vice chair for quality; and Dr. Ramon Figueroa as vice chair for faculty development. Eight other faculty members also received promotions, which she says were “very much deserved.” On the technologist side, she worked with her departmental administrative director to move several lead technologists into manager roles, helping to build more effective management from the middle, move away from silos and empower staff to weigh in on key processes such as budgeting or process improvements. “It’s really led to us working more closely and effectively,” she says.

Another heavy focus was on recruiting. She hired a dozen new faculty members over the past three years, strengthening the department by a full third, to help meet burgeoning growth in patient cases and add valuable administrative and leadership experience. Faculty hires have also brought additional depth and skill into the department, including skills in newer treatments such as theranostics, which combines two radioactive drugs, one to diagnose and another to treat tumors; TACE or transarterial chemoembolization, which combines local delivery of chemotherapy with synthetic agents to block blood flow and isolate chemotherapy inside a tumor; prostatic artery embolization to improve lower urinary tract symptoms in patients with benign prostatic hypertrophy; and palliative care in interventional radiology, which helps improve quality of life for patients with life-threatening diseases.

In diagnostic radiology, new faculty members have helped build the department’s strength in multiple areas such as sports imaging, functional MRI, 3D visualization and fabrication, cancer imaging, CT radiation dose optimization and structural cardiac imaging.

On the education side, she has embraced MCG’s curriculum focusing on problem-based learning — a big change, she says, from her days in medical school when it was just regurgitation of memorized facts for the first two years. “For one thing, I think it’s more fun in terms of a medical school experience, but also it involves radiology earlier, which is great,” she says. “We are very involved in most diseases, [and] there’s going to be imaging in the vast majority of those pretty early on in the diagnostic phase. They’re very excited, our faculty, to be doing this and having more contact with medical students and being involved early on.”

Then in February, with the support of MCG Dean Dr. David Hess and Augusta University President Dr. Brooks Keel, the Department of Radiology unveiled its first dedicated research MRI machine, to help carve out precious research time for a variety of studies, which historically had to compete against clinical patients for MRI time. Four pilot projects — including studies on multisensory perception, brain aging, brain health and 3D printing of the aorta — have already been able to capitalize on the new equipment, which functions like a core resource for any interested investigator across AU or the University System of Georgia. It’s a “great step,” she says. “There are plenty of researchers at MCG and even outside of MCG who can use MRI for their research projects and grants.”

With the support of Dr. Charles Howell, ’73, CEO of AU Medical Associates and former surgeon-in-chief of the Children’s Hospital of Georgia and generous donors, a new PET/CT scanner installed in CHOG adds capacity for pediatric patients, and more importantly opens up treatment for those needing sedation, typically most pediatric and some adult patients. While a pediatric PET/CT was available at the nearby Georgia Radiation Therapy Center, facility restrictions did not allow for sedation. The department also recently opened the health system’s first freestanding outpatient center, AU Health Imaging — located a half-mile west of AU West Wheeler — featuring two MRIs, a CT scanner, a 3D mammography machine, ultrasound, X-ray and DEXA, which measures bone density. “It’s very exciting,” she says. “It makes it more convenient and sometimes less expensive for patients.”

Her future goals are just as ambitious. “One thing I really want to do is develop a radiology patient advisory council,” she says. “You know, we probably see more patients volume-wise than any other department except maybe the lab. We’re talking about 1,000 patient exams a day, on probably about 700 patients…I don’t see how we can make our processes optimal unless we invite the people whom we are taking care of into the discussions about process improvements. We — physicians and technologists and nurses — are expert at providing the right care, including imaging, but we’re not the experts at experiencing care or experiencing illness. We have to ask patients, of course. We have to do that.”

“… we probably see more patients volume-wise

than any other department except maybe the lab.

We’re talking about 1,000 patient exams a day,

on probably about 700 patients ….”

–Dr. Annette Johnson

It goes back again to her own experience having surgery, that turning point in her life and choice of career. She still recalls the noisiness of the hospital floor, the lengthy wait times for responses to her call button, and then the stress of restricted visiting hours when she was barely 20 and recovering alone in the hospital. “Once you experience that, you think about it,” she says.

Johnson also wants to streamline a process that hospitals struggle with nationwide. While radiology has a key role in diagnosing suspected diseases or conditions, incidental findings — discovering a small lung mass during an X-ray after someone has been in a car accident, for example — also can make up a large part of what radiologists do. Studies vary, but a 2018 study in American Family Physician found that 45% of CT scans, 38% of CT colonoscopies and 34% of cardiac MRIs produce incidental findings.

The challenge is capturing those incidental findings in a way that ensures that appropriate follow-up happens. While only a small percent (from 1.4% to 12.8% according to a 2018 study by The BMJ) are potentially serious, for that minority of patients, such a finding could be very impactful, says Johnson — requiring failsafe communication, which unfortunately is not currently in place. “This is a national-level concern,” she says. “We need a process that is very systematic, with a backup to track every single one of those … I know it’s the right thing to do.”

Recent issues

As with many other departments, the past 20 months have been heavily focused on COVID-19. Radiology was on the front lines, along with respiratory therapy, nursing, lab workers and many others, through its primary role in managing X-rays and CT scans of patients’ lungs. But the past several months have also turned Johnson’s focus to diversity and inclusion.

After the May 2020 murder of George Floyd, “I just decided we have got to talk about this,” says Johnson. “It can’t be good not to talk about it.”

“The way I see it, how can we ever be really great if we haven’t taken all perspectives into account? How can we take care of a patient population that we don’t reflect very well?” she says. “I don’t think we can expect to be successful if we ignore the experiences and the perspectives of large subgroups within our population and among us. I also don’t think we can ever be great pretending that race for instance doesn’t matter. I just don’t think we can be great until everybody truly feels like they belong and their voice is heard.”

She conducted a departmentwide survey — staff, faculty, administrators, trainees — to ask a few simple but telling questions, including whether anyone had experienced work situations where race felt like a factor or where leadership exhibited racist behaviors.

Responses were anonymous and revealed “painful but incredibly valuable insights,” says Johnson. That led to the development of monthly departmental conversations focusing on racial injustice, coordinated by health system chaplains Jeff Flowers and Brennan Francois and held at the campus’ Lee Auditorium.

Those conversations have borne fruit, turning into exercises with department leadership to develop strategies to try to help everyone in radiology feel a sense of inclusion. More specific changes included holding an open recruitment process for every position, top to bottom, with interviews led by a panel. In turn, says Johnson, it has already led to more diversity in staff leadership. “I don’t want to give that sense we were checking a box,” she adds. “It’s because we found great candidates … Because we opened the recruitment process up and because we convinced people we’re doing this differently, we had great applicants and we’ve been able to increase the diversity in our staff and in our staff leaders.

“It’s definitely made us stronger.”

Past, present and future

Johnson goes far back enough, she says, that she has lived through several periods when radiology as a field feared for its future. Picture archiving and all digital imaging, even AI, have appeared to be threats that might eliminate the need for human radiologists. But, she says, “we will always need people to give data meaning. … [And] the reality I live in is that referring physicians and patients seem to rely on our expertise now more than ever.”

Looking back, she is in the unusual place of being able to say, with conviction, that she has enjoyed every step of her career and her life. Even that surgery she had as a 20-year-old. “Almost every experience makes us who we are,” she says. “That one changed my whole career path.”