A tiny worm called the C. elegans is enabling scientists to explore the emerging theory that Parkinson’s disease starts in the gut.

Key to the condition known to produce uncontrollable shaking, but also characterized by cognitive problems and gastrointestinal distresses like constipation, is a sticky, toxic form of the protein alpha-synuclein, which literally gums up the works of our neurons and kills them.

Although it may seem counterintuitive, there is evidence from science labs like Neuroscientist Danielle Mor’s, PhD, that the toxic protein aggregates in the neurons in the gut before it interferes with neurons in the brain. The collection of destructive alpha-synuclein, called Lewy bodies, also has been found on autopsy in neurons embedded in the wall of the gastrointestinal tract of patients with early Parkinson’s.

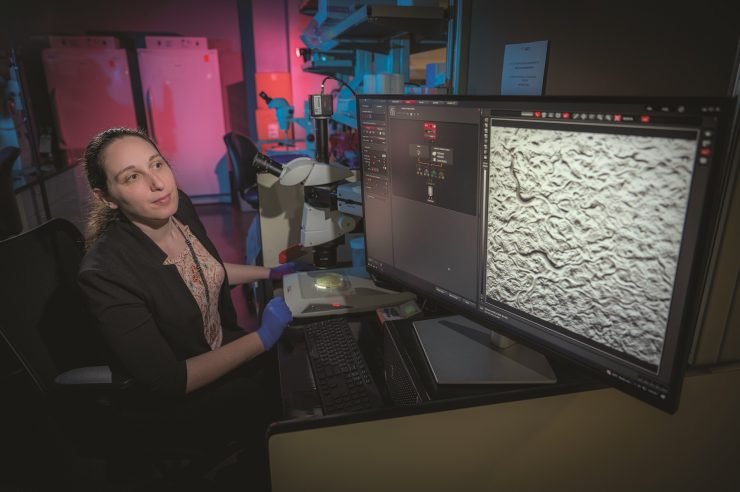

“This is now a hot area of research,” says Mor, a faculty member in the Department of Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine at the Medical College of Georgia. “I think we need to be intervening at the stage of the gut and that is honestly pretty exciting.”

It’s known that neurons in the gut regularly communicate with those in the brain and vice versa but just how the alpha-synuclein gets messed up in both is another uncertainty.

Still in animal models, scientists like Mor have watched the sticky wads get spit out of one neuron and get taken up by the next. They’ve also watched the sticky wads in the gut travel up the spinal cord into the brain. It appears this unfortunate sharing occurs primarily between neurons that already connect and communicate, says Mor.

She just received a two-year $400,000 Early-Investigator Research Award from the U.S. Department of Defense that is helping her learn more about the effects of gut-derived alpha-synuclein on cognition, how it gets inside neurons and whether there are existing drugs that can deter the cognitive impact.

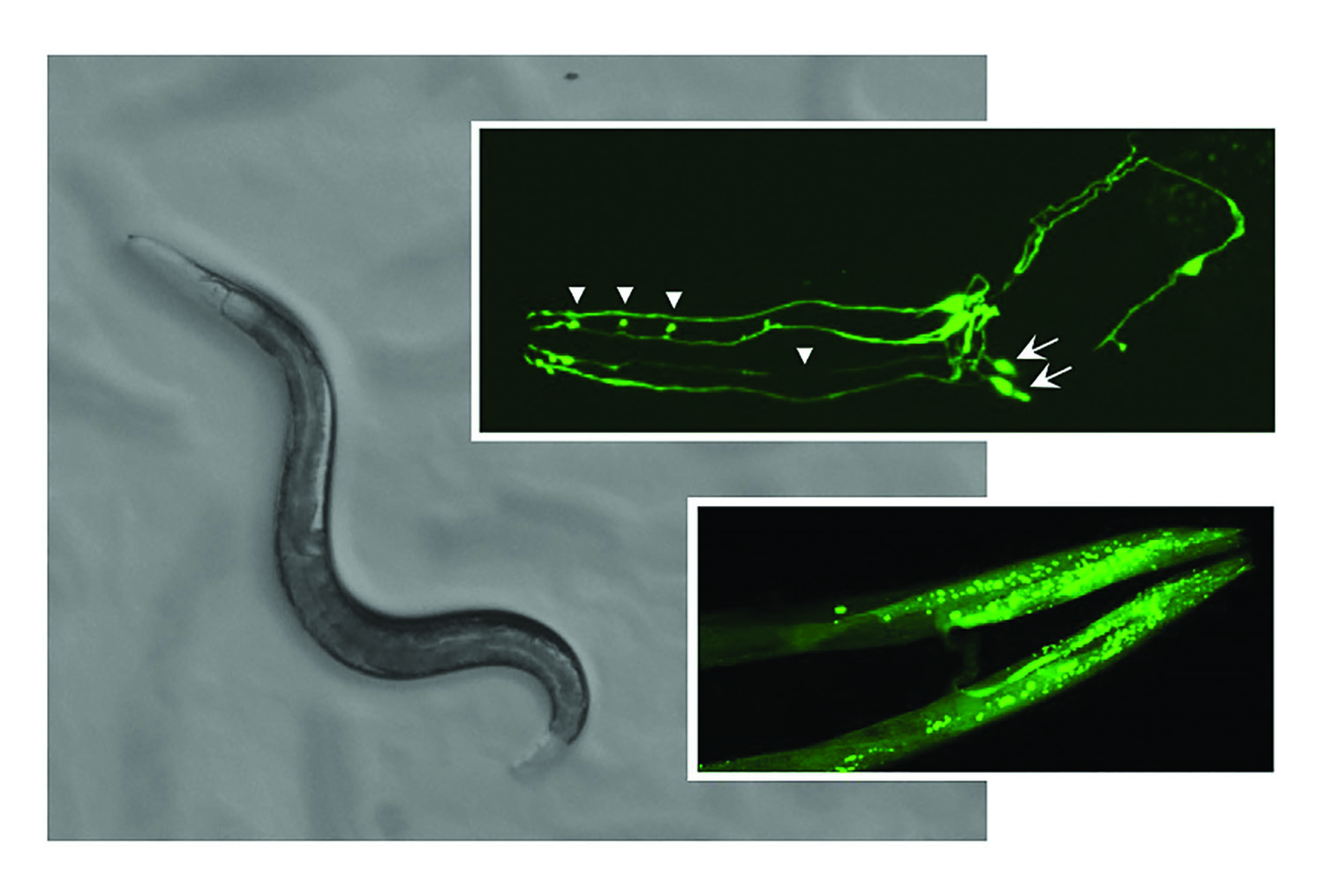

Mor is among the first scientists to look at how alpha-synuclein in the gut affects cognition. And the transparent-throughout-life C. elegans are a great model for pursuing answers, Mor says.

These nematodes, or roundworms, despite their size of about .039 inches, have a gene number and gene pool similar to humans. They also have a digestive tract and many of the same neurotransmitters as humans as well as an alimentary nervous system, which is basically a network of neurons in the gut and where Mor thinks the early alpha-synuclein first congregates and why she developed her worm models.

For the newly funded studies, she is focusing on the cognitive problems that often surface later in Parkinson’s. So as the destructive alpha-synuclein travels from gut to brain she is testing learning and memory in the worms, which she says, again seemingly counterintuitively, is not that tough to do.