Disease of the microscopic blood vessels that feed the white matter of our brain is associated with worse cognitive function and memory deficits in individuals with Alzheimer’s, scientists report.

Disease of the microscopic blood vessels that feed the white matter of our brain is associated with worse cognitive function and memory deficits in individuals with Alzheimer’s, scientists report.

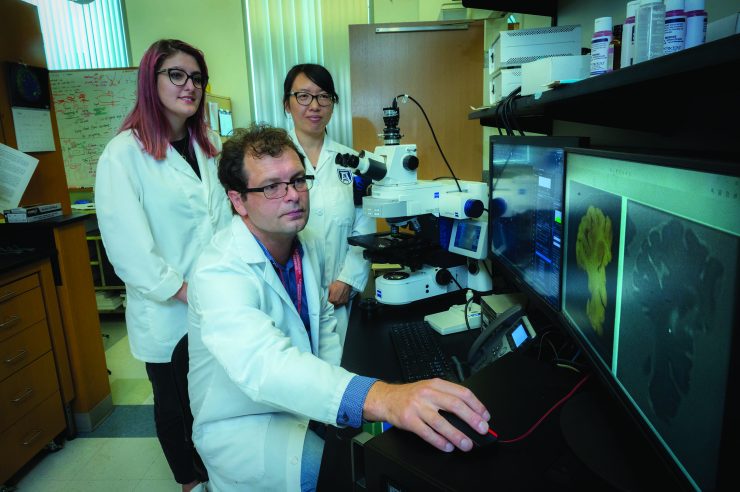

“The main message of this paper is the mixed pathology as we call it — microvascular disease and Alzheimer’s — is associated with more brain damage, more white matter damage and more inflammation,” says Zsolt Bagi, PhD, vascular biologist in the Department of Physiology at the Medical College of Georgia.

Theirs and other recent findings suggest that some people with Alzheimer’s who have brain changes widely associated with the condition, like amyloid plaques, may not develop dementia without this underlying vascular dysfunction, the researchers write in the journal GeroScience.

“We are proposing that if you prevent development of the microvascular component, you may at least add several years of more normal functioning to individuals with Alzheimer’s,” Bagi says.

He and by Stephen Back, MD, PhD, pediatric neurologist, Clyde and Elda Munson Professor of Pediatric Research and an expert in white matter injury and repair in the developing and adult brain at Oregon Health & Science University, are co-corresponding authors of the new study.

The good news is that vascular disease is potentially modifiable, Bagi says, by reducing major contributors like hypertension, obesity, diabetes and inactivity.

The scientists looked at the brains of 28 individuals who participated in the Adult Changes in Thought Study, or ACT, a joint initiative of Kaiser Permanente Washington Research Institute and the University of Washington, whose scientists also were collaborators on the new study.

Their focus in the studies was the white matter, which accounts for about 50% of the brain mass, enables different regions of the brain to communicate and is packed with long arms called axons that connect neurons to each other and to other cells across the body like muscle cells. And, the microscopic arterioles that directly feed white matter with blood, oxygen and nutrients.

They wanted to test their theory that when these hair-thin arterioles had difficulty dilating and so supporting this part of the brain, it resulted in changes to the white matter that were evident on sophisticated MRIs, especially when microvascular problems coexisted with the more classic brain changes of Alzheimer’s.

They found that the arterioles of those who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and dysfunction of these tiny arteries did have an impaired ability to dilate in response to the powerful blood vessel dilator bradykinin, compared to those without obvious microvascular dysfunction. Problems with dilation were associated with white matter injury and changes to the white matter structure that were visible on MRI.