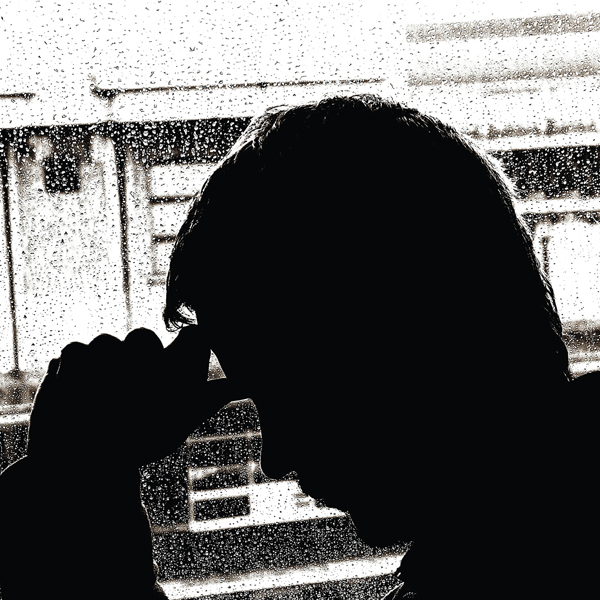

Skyrocketing Suicide Rates Demand Hard Look at Depression

One of our anesthesia partners had been through a contentious divorce a few months earlier, but that seemed like old news now. A colleague and I worked with him in obstetrics that last day. He had draped a white hospital blanket around his shoulders over his blue scrubs. Shroud-like, he wore that blanket all day, sitting in a fetal position in our office when he wasn’t doing an epidural or some other task. No eye contact and no conversation. It looked like he was trying to disappear into himself.

What Were They Thinking?

We knew he was depressed, but honestly, we thought he was overdoing it a bit. Let’s go. Grow up. We’re anesthesiologists, not psychologists.

He was a great doctor. I remember watching him do a blind popliteal block, demonstrating the difference between the common peroneal and tibial nerves by electrical stimulation. Rhythmically, the toes went up, then down. In that instant, I transformed from a colleague to an admirer.

I didn’t give him a second thought after ending my shift that day, assuming I’d see him the next day. But I never saw him again.

I heard he left a note before taking a fatal overdose. What was he possibly thinking?

[su_pullquote align=”right”]The American Medical Association cites a 12 percent lifetime depression risk for physicians, but the number is self-reported and probably higher.[/su_pullquote]

A hospitalist who worked out in my gym – I’m not sure I even knew his first name – checked on his patients one day, then went home and shot himself. He left a wife and two children.

A young surgeon at my hospital, superbly trained and a nice guy to boot, missed a day of work and was found dead at home. Maybe an overdose; I don’t know for sure.

This all happened in the space of a couple of years. No alarm bells went off. Each tragedy was seen as isolated and unrelated.

Powering Through

But these suicides are related, if only by the fact that they were all physicians. Doctors talk about patients, we talk about nurses, we talk about the hospital, but we don’t talk about our struggles with depression. That would seem unprofessional and even uncool. We are the strong ones. We operate on a higher plane. We can stay up all night and take care of the sickest of the sick. We don’t need any help. We can power through anything, including mental illness.

Medicine is complex, and the demands are ever-growing. We operate in an environment of perfection. We feel stress but try not to show it. The only given is that everything must work 100 percent of the time, including us.

Suicide is usually due to untreated or poorly treated depression. Combine depression with alcohol abuse and the risk skyrockets. The American Medical Association cites a 12 percent lifetime depression risk for physicians, but the number is self-reported and probably higher. We fear being stigmatized. Many of us do not recognize the symptoms in ourselves. And we know how the body works. When we make suicide attempts, we succeed.

Under-Reported Problem

This is not solely a physician problem. More Americans die of suicide than automobile accidents, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The New York Times reports that suicide rates have increased 28 percent among 35- to 64-year-olds and have increased almost 50 percent among men in their 50s. I am certain that even these scary numbers are under-reporting the problem. Suicide is a national epidemic. I have one degree of separation from over 15 people who have committed suicide in the last five years. Just recently, siblings of two nurses I know committed suicide within a week of each other.

Something is going on in this country, and we have no solutions. Some experts blame the economy; others state that baby boomers cannot deal with setbacks. No one can deny that family and community connections have frayed.

Even as I was writing this essay, a close childhood friend committed suicide. After spending five weeks together in Europe as 19-year-olds, we emerged better friends than when we left. We lost contact after he moved to New York; I’m not sure why. His family had no idea he was depressed. I was told he was in perfect physical health.

Around the same time, my medical school roommate was diagnosed with an extremely lethal and aggressive cancer. The cancer metastasized to his thoracic spine. Overnight, he became paralyzed. In spite of these horrific setbacks, he has found increased meaning in his relationships with his wife, his children, his friends and his God. His blog is filled with hope and laughter. For the past year, he has fought for every second. Why do some give up? Why are more and more of us giving up?

No Second Chance

We should all learn to recognize depression in our colleagues, our family members and ourselves. I should have dragged my partner to the emergency room. I’ll never have a second chance to do that. In anesthesia, one of my partners told me that we earn our money by saving one or two lives a year, those with unrecognized airway or cardiac difficulties. I never thought that the life I could save could be one of my partners.

The best definition of suicide I’ve heard is a permanent solution to a temporary problem. I totally missed the temporary problem. I did not understand my partner’s pain. I did not understand his motives. What I now understand is that I should have done something. I could and should have tried to save him. I should have confronted him.

I simply didn’t realize how lethal depression could be.