About 17% of women with unexplained infertility also have gene variants known to cause disease, from common conditions like heart disease to rare problems like ALS, Medical College of Georgia researchers report.

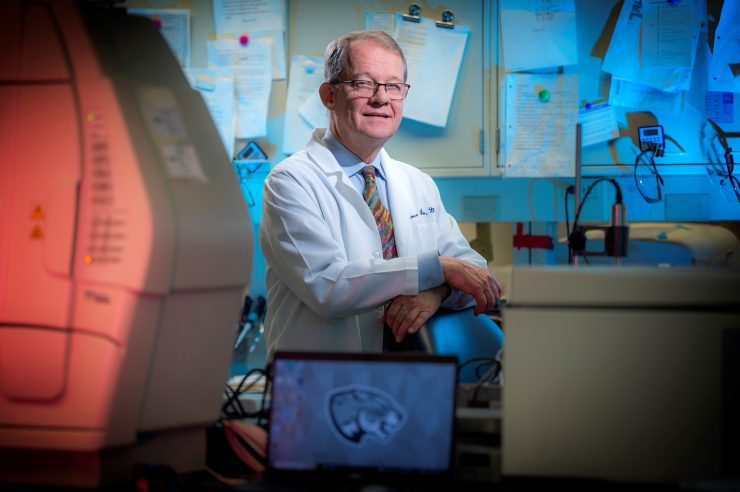

Theirs appears to be the first study to identify an increased prevalence of disease-causing genetic variants in females with unexplained infertility, the team, led by Lawrence C. Layman, MD, reports in the New England Journal of Medicine.

They hypothesized that genetic disease creates a predisposition to infertility and subsequent medical illness and their findings support that link, they write. Females with infertility, for example, have been noted to have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

“The connection to diseases has been known, but what has not been known was if there was a genetic connection. That was the purpose of this study,” says Layman, a reproductive endocrinologist and geneticist who is chief of the MCG Section of Reproductive Endocrinology, Infertility and Genetics.

The investigators note that while clear, common pathways between infertility and conditions like heart disease, still have not been established, “a strong association between infertility and future disease can still assist in early detection, genetic counseling and intervention.” Fertility could be in effect a “biomarker” for future medical illness, they write.

They sequenced the exomes, which contain the protein-coding regions of genes, of 197 females ages 18 to 40 with unexplained infertility, a percentage that comprises about 30% of infertile females, to look for variants in genes that were known or suspected to cause disease.

They found 6.6% of the females they studied had variants in 59 genes termed “medically actionable,” which means they are likely to cause conditions like heart disease and breast cancer but there are interventions, lifestyle and/or medical, that might remove or at least reduce their risk. By comparison about 2.5% of the general population have been found to have variants in these genes.

An additional 10% of the females had gene variants known to cause disease for which little to no action could be taken to ameliorate the problem, like Parkinson’s disease, Layman says.