Chairman’s initiatives Put Time on Stroke Patients’ Side

There are about 100 billion Neurons in the brain, and a stroke kills 32,000 each minute.

The Clock Starts

“You can’t think too much about it in a crisis; you just have to act,” says Dr. David Hess, chairman of the Medical College of Georgia Department of Neurology. “You think about it later.” He thinks about it a lot.

Most strokes begin when a blood clot shoots to the brain. “You are up talking, and all of a sudden, your arm drops. You can’t speak,” Hess says, referencing typical symptoms that indicate the onset, also known as last-seen-normal, or LSN. “That is when the clock starts.”

Some level of permanent damage – a limp or slightly slurred speech, for instance – is virtually inevitable if a clot persists 15 minutes or more. More time equals more damage. Tick tock, tick tock.

While most cells die in the first minutes and hours, injured cells in the penumbra – the area surrounding the stroke site – can continue dying for 24 hours. The penumbra can be vast, even larger than the original stroke site. With every passing minute, the stroke core grows, and the penumbra shrinks. “Eventually, the core will be the penumbra, and there is nothing we can do,” Hess says. Tick tock, tick tock.

[su_note note_color=”#efefee” text_color=”#000000″ class=”story-side-box”]Hess at a Glance

• Alumnus of University of Maryland School of Medicine

• Alumnus of University of Maryland School of Medicine

• Internal medicine residency, Allegheny General Hospital

• Neurology residency (year as chief resident), MCG

• Cerebrovascular fellowship, MCG

• Member, Alpha Omega Alpha, Gold Humanism Honor Society

• Member, American Heart Association Telestroke Committee

• Member, AHA Scientific Sessions Committee Member, National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke Clinical Trials Study Section

• Chairman, NINDS Clinical Trial Special Emphasis Panels

• Co-Founder and Founding CEO, REACH

• Chairman, Board of Directors, REACH

• Included in America’s Top Doctors directory

• Clinical Advisory Board, Athersys

• Editorial Board of Stroke, Cell Transplantation, Experimental & Translational Stroke Medicine, Brain Circulation

• Associate Editor, Translational Stroke Research[/su_note]

The goal is to break up the clot, stop the cell death and arrest the process, says Hess, who has led the neurology department since 2001. Five years before he came on board, the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of the clot-busting treatment tissue plasminogen activator, or tPA, potentially widened the treatment window from three to four and a half hours. (Ongoing debate continues about who benefits from this expanded window versus who just gets an increased risk of bleeding, a well-established risk of tPA.)

Buying Time

Still, only about 5 percent of patients with a clot-based stroke get tPA all these years later. And that was at the heart of what kept messing with Hess’ head.

He and his colleagues were frustrated that even patients brought directly to Georgia Regents Medical Center often arrived too late for tPA, never mind the patients transported from smaller facilities miles away. In the heart of the stroke belt and in a state that is largely rural, Hess and a small team at MCG decided to act.

“People talk about the heart of the matter, but our brains are really us,” says Hess, and he and his colleagues were weary of stroke patients losing too much of themselves. He and three colleagues – Dr. Robert Adams, a former faculty member; Dr. Sung B. Lee (’01), now a neurologist in Hawaii; and Dr. Fenwick Nichols, professor of neurology and radiology – pieced together the first version of REACH. They brought on Dr. Sam Wang, now a health care IT consultant in Ann Arbor, Michigan, who then had worked for a belly-up dot.com company. With a little money, a lot of excitement and the help of Bill Hamilton, former neuroscience administrative director, they literally duct-taped together the earliest cloud computing system.

The system initially enabled MCG stroke specialists to remotely and rapidly examine and help treat patients in McDuffie and Burke counties, both at least a half hour’s drive from Augusta. Early next year, the Alpharetta, Georgia-based REACHHEALTH will unveil REACH 5.0, a high-tech but user-friendly model with improvements including lifelike resolution and the ability to build the electronic medical record on the same screen where the doctor and patient are interacting.

[su_pullquote align=”right”]“People talk about the heart of the matter, but our brains are really us.” –DR. DAVID HESS[/su_pullquote]

Extending Their Reach

Hess sounds a bit like a child having his best birthday as he describes the latest iteration.

“When you have a stroke and you are 50 years old, which is not uncommon here, your whole life can be destroyed,” he says, citing the life-changing implications of the technology. The MCG-based team was among the first worldwide to prescribe tPA over the Internet. A decade ago, in a study published in the journal, Stroke, they showed that stroke patients in rural communities could be assessed and treated via the wireless network just as well as patients in bigger-city emergency rooms. Today, MCG neurologists serve about 30 smaller facilities in Georgia via REACH, and 10 states are using the system.

MCG’s longtime medical education partner, St. Joseph’s/Candler Health System, based in Savannah, Georgia, also uses the system, partially staffed by seven MCG neurologists. In fact, MCG helped educate and train many of the neurologists in that part of the state through the hub-and-spoke model – a sort of neurologist extender made possible by REACH. Faculty in the area include Dr. Jill Trumble (’08) and two former MCG stroke fellows, Drs. Shannon Stewart (‘08) and Mihaela Saler.

The MCG team is also doing its part to increase treatment options. For instance, their clinical trials have shown that the antibiotic minocycline can reduce stroke-related inflammation. They have also taken a lead in evaluating the use of adult, bone marrow-derived stem cells, developed by Cleveland-based biotech firm, Athersys Inc., which appear to help heal the fragile penumbra. REACH has enabled patients statewide to also benefit from some of these emerging therapies.

Georgia Regents Medical Center, designated an Advanced Comprehensive Stroke Center by the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, also offers mechanical thrombectomy, recently endorsed by the American Stroke Association for removing huge clots – some an inch or more in diameter – that tPA can’t dissolve. And in 2012, Hess’ team published results in the journal Stroke, indicating that successive, vigorous bouts of leg compressions – called remote conditioning – following a stroke trigger natural protective mechanisms that reduce damage and double the effectiveness of tPA. Similar results have been shown in patients with heart disease; dementia is the next frontier.

[su_note note_color=”#efefee” text_color=”#000000″ class=”story-side-box”]Solid Roots

Dr. David Hess’ calm-on-the-outside, driven-on-the-inside demeanor has some seriously solid roots.

Dr. David Hess’ calm-on-the-outside, driven-on-the-inside demeanor has some seriously solid roots.

His mother, Eleanor, was 40 when he was born. She was a second-generation Norwegian, her father a merchant marine who loved America and one day just jumped ship. Eleanor, who grew up in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, was a gifted organist and lived life “tough as nails” until she started breaking hips and becoming physically fragile. She died at age 97.

His father, Raymond, started out in a one-room schoolhouse in rural Pennsylvania and became the first college graduate in his family. He was in the Navy, became a research chemist, and later a salesman. Raymond was one of those people everybody liked. He had a terrific singing voice, so he and his wife made beautiful music together. He was still blond and looked 60 at age 80 and was nowhere near ready to die, but prostate cancer had spread to his bones.

Hess’ parents taught him important life lessons about integrity and honesty as he grew up in Westfield, New Jersey, a small city on the edge of the volcanic Watchung Mountains. He wanted to be a doctor, the first in his family, for as long as he can remember. Doctors were early heroes to Hess, who had horrific ear infections as a child that were once confused with meningitis. He remembers one Christmas Eve spent on the floor because of the pain. His pediatrician advised his parents to let him have the tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy that would get him off the floor.

Hess’ wife, Diane Degrandis Hess, was growing up not very far away in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, the home of Arnold Palmer and the training camp for the Pittsburgh Steelers. They met when he was an internal medicine intern at Pittsburgh’s Allegheny General Hospital and she was a medical social worker. They had four children in seven years, two boys and two girls.

Now married for 30 years, at MCG for nearly that long and chairman for over 14 years, Hess, 58, admits he is one to hang onto people and places. “You have to blast me out of something. I will always be married to one woman and I believe in sticking with something no matter how bad it gets,” he says, smiling at the juxtaposition of the two thoughts. Because really, there is no questioning where Hess’ head and heart are for this woman, a prolific church volunteer and natural organizer, who has spoiled him and the children rotten.

While his wife’s organizational skills would no doubt be a real benefit at Hess’s office, at least a few pictures there provide more insight into the man, even if they are sometimes a bit dusty. There is a small, framed picture on the wall of Hess with Pope Benedict XVI, who he describes as a humble man he was nervous to meet that day. But it’s Pope John Paul II who is one of his true heroes. “He survived the Nazis and communists, saw all his close friends and family murdered. This guy has such, such spiritual power, moral power that literally he brought down the Soviet Union,” says Hess.

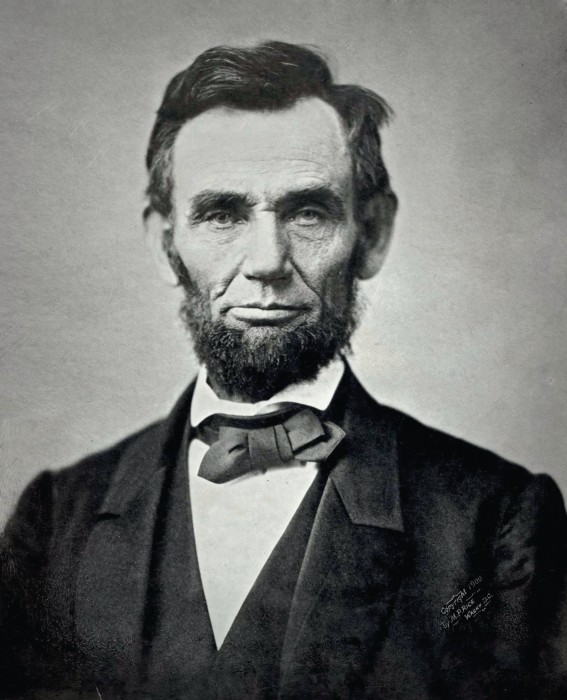

The man who gets a wall to himself is Abraham Lincoln. “I have always admired him. He took a strong stand and stood by [his convictions], no matter how difficult it became. He saw [the Civil War] as his epic struggle and it pained him severely. The way Lincoln wrote and talked exemplified his passion, Hess says. The 300-word Gettysburg Address, which Lincoln wrote on a train and thought would have no impact, slays Hess to this day. [/su_note]

Common Ground

Stroke and dementia have a lot of common ground, including the risk factors of aging and vascular troubles. With an aging population that is half female (the gender at higher risk), vascular dementia, the second most common dementia cause behind Alzheimer’s disease, is also now a headliner. Like stroke 20 years ago, vascular dementia has no FDA-approved therapy.

Remote conditioning uses a blood pressure cuff-like device to periodically briefly restrict blood flow to an appendage, thereby increasing blood flow to other body areas, including the brain. Increased bouts of flow activate endothelial cells lining blood vessels, initiating a series of natural protective mechanisms. Interestingly, the mechanisms seem most active in areas of impaired flow, such as those deep inside the brain, where most dementia has its roots. Regular exercise likely reaps similar benefits.

A recent translational grant from the National Institutes of Health is helping Hess garner more laboratory evidence for the treatment, and he is seeking funding for a clinical trial of remote conditioning in dementia.

“What we want to do long term is find people at risk for dementia, then condition them chronically with the device at home,” he says. When the problem is so pervasive, forestalling dementia for even a couple of years can have a huge impact.

“This is the big epidemic coming,” Hess says. Tick tock.