Inaugural Faculty Member Sank Teeth into Career

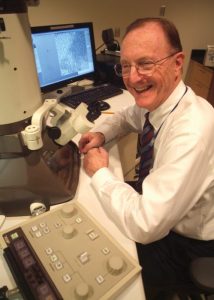

Dr. David Pashley has made too many lab discoveries to count during his half-century dental career, but only a few have yielded such startling “aha!” moments that he was too excited to sleep.

This was one of them.

A Sensitive Subject

Pashley, who had joined The Dental College of Georgia in 1970 when recruited from the University of Rochester by founding Dean Judson C. Hickey (see “A Package Deal,” page 12), had drawn on his extensive training – a PhD in physiology in addition to his dental degree – to solve a vexing problem: how to eliminate the pain of tooth sensitivity. The year was 1979, and it was a resident’s research project that nudged him toward the dilemma, which was generally perceived as more annoying than crucial by the average dentist. Sure, dentists hated that some of their patients winced in pain when eating an ice cream cone or enduring a cold blast of water during a cleaning. But tooth sensitivity – the pain resulting when exposed dentin comes in contact with a shot of hot or cold air, liquid or food – was generally endured as an unavoidable evil, both by patient and clinician.

But Pashley, who has never encountered an obstacle he didn’t want to overcome, welcomed the resident’s interest in seeking a solution. “Dentin looks hard as a rock, but it’s very, very porous,” Pashley says. “The pores are microscopic, so it’s really a sieve. That’s why it’s so sensitive.”

Together, he and the resident began exposing dentin to various chemicals to see whether any could plug the pores that reached to the roots and caused that piercing shot of pain upon contact with the nerve. “After we knew the structure of dentin and how big the tubules were, we had to find things that would go down into the tubules and plug them,” Pashley says.

Exhibit A

He laughs that he often cites the experience as Exhibit A when dental students balk about having to learn seemingly extraneous subject matter. “So many of my students have complained over the years about having to learn so much chemistry,” he says. “They’ll say, ‘When are we ever going to use this?’ I tell them I use everything I’ve ever learned.”

The chemical Pashley found to be most effective – indeed, astonishingly effective – in plugging the pores was calcium oxalate. “It’s bright white and works with the dentin to instantly form acid-resistant crystals that fit into the tubules and work like a charm,” Pashley says.

“I said, ‘Wow, this stuff clogs dentin better than anything!’ I was tremendously excited.”

Pashley rushed to the office of Dr. William Moretz (then-president of the university then called the Medical College of Georgia) and said he wanted to patent the technology. Just one problem: The university didn’t have a patent policy. But Moretz appreciated the significance of the finding and directed his staff to develop one. Once it was in place, Pashley obtained the patent — a boon to science, the university and his lab.

‘The Rascals’

But a patent went only so far in tapping into the potential of the discovery. “There was no infrastructure in place,” Pashley says. “Just getting a patent doesn’t cover marketing. I couldn’t get any of the big companies interested.”

He finally persuaded a small dental-materials manufacturer to partner with him in creating an oxalic-acid treatment that dentists could apply in the office. The treatment was highly effective but temporary. Pashley knew the long-term solution lay in adding the chemical to everyday products such as toothpaste that people could use regularly at home. Still, the major producers of those products dragged their feet.

“Patents expire in 17 years, and I saw that they were going to wait me out, the rascals,” Pashley says with a chuckle. That’s exactly what happened: As soon as the patent expired, the market exploded with products using his technology to target tooth sensitivity.

Pashley adds breezily that he wasn’t entirely left out in the cold: The big guns turned to him as a consultant, a role he still plays as his technology is incorporated into an increasingly broad array of products, including dentin desensitizing strips similar to mouthwash and tooth-whitening strips.

And although he regrets that neither he nor the university received their full due for the discovery, Pashley has the satisfaction of knowing that the world of science took notice. He collaborates with researchers throughout the world and received the Augusta University Research Institute’s 2011 Lifetime Achievement Award. His studies have been continually funded by the National Institutes of Health, the most competitive source for grant-funding, for virtually the duration of his career.

“That’s your tax dollars at work,” he says with his trademark understated wink and nod.

Mutual Support

And tooth sensitivity is just one of many frontiers he has conquered, having developed countless innovations in dental materials. Most recently, for instance, Pashley created a technique that significantly extends the lifespan of tooth-colored composites, making fillings and sealants much more durable. He notes wryly that his wife, while hugely proud of the accomplishment, wasn’t a big fan of that particular study.

“I was about to retire when I wrote a five-year grant [seeking funding for the research],” he says. “Well, research grants are difficult to get, and I didn’t think my proposal would be approved. But they loved it.” He pauses mischievously for the upshot: “My wife said she’ll kill me if I write another five-year grant.”

With the study recently completed, he retired for good this spring.

And his wife wasn’t nearly as cranky about the delay as she intimated. After all, who is she to talk?

Pashley and wife Edna, his college sweetheart, were raising their two young sons after moving to Augusta when she floated an idea. “We were raking pine straw in the yard one day and she said, ‘What do you think about me going to dental school?’” Pashley recalls. “I said I thought it was a good idea.”

His wife recalls a less understated response. “When I asked if he thought I could do it, he said, ‘Oh, yeah! You can do anything!’”

She had taught high school science during her husband’s training, and Pashley was happy to support her dreams. She applied to The Dental College of Georgia and was accepted. Her husband marvels in retrospect that she managed to keep so many balls in the air. “She would make a week’s worth of meals on Sundays and organize a week’s worth of clothes for the boys,” he says. “The kids hardly even noticed she was in school.”

Shop Talk

Upon graduation in 1979, she completed a residency in pediatric dentistry, then hung her shingle on Central Avenue in Augusta. “The boys (Steve and Tom) would walk to her office from school,” Pashley says. “I remember once she had Steve count the root tips of a tooth she’d extracted to make sure she’d gotten everything out. She handed him the bloody tooth and he backed up against the wall and started fainting.”

Pashley laughs that the couple concluded their son needed more, not less, exposure to their livelihood. “I said, ‘We can’t have him fainting over a little drop of blood!’” Pashley says.

Pashley himself put his sons to use when he was assisting his colleague, Dr. Gary Whitford, in a fluoride study. As study participants, both boys had to provide urine samples to determine their fluoride content. Pashley remembers son Tom quipping, “My mom’s a pedodontist (then the title of a pediatric dentist) and my dad’s a pee-dodontist.”

Between bloody extracted teeth, urine samples and interminable shop talk at home, both boys opted out of following in their parents’ footsteps.

“That’s what you get when you have two dentists in the house,” Pashley observes merrily.

Best Friends

Today, son Steve is a tax attorney in Chattanooga, and Tom is president of the Pinehurst Golf Resort in the North Carolina Sandhills. At press time, Pashley and his wife, who herself joined and retired from the DCG faculty after selling her private practice, were planning to move to the area to be closer to their grandchildren. Pashley said he might even have to consider taking up golf.

“I’m a workaholic,” he concedes. “A round of golf lasts four hours. I could write half a paper in four hours.”

But although he’ll miss his career, he relishes the thought of a slower pace of life, particularly considering that his college sweetheart will still be by his side to enjoy the next phase of their adventure. “She’s my best friend,” he says simply. “That’s what makes it work.”

His colleagues are already mourning his retirement. Whitford, for instance, notes, “Dave and I were recruited together from the University of Rochester, and for the next 45 years, our labs have been located next to each other. Our mutual love for teaching and research produced a valuable and fruitful collaboration that will be sorely missed.”

Dr. Frederick Rueggeberg, professor in the Department of Oral Rehabilitation, heartily concurs. “Dave is a great role model for everyone to look up to and to emulate in their own lives, both personal and professional,” he says, citing characteristics including selflessness, boundless curiosity and an utter lack of ego. The latter, he says, accounts for Pashley’s generosity in sharing his expertise with others worldwide, welcoming collaboration for the good of the dental profession.

Another colleague in the Department of Oral Biology, Dr. Mohamed Al-Shabrawey, admires Pashley for “thinking before he talks and delivering the right message. He is the most humble and smiling professor.”

Dr. Mohamed Sharawy, professor of oral biology and like Drs. Pashley and Whitford one of the original Dental College of Georgia recruits, adds, “I consider David my best friend. He’s a well-respected and competent colleague and brother.”

In addition to taking up golf, Pashley looks forward to voracious reading and writing in retirement. And his wife doesn’t expect him to completely leave dentistry in the dust.

“He’s still editing papers,” she says. “He does a very good job. And he’s always teaching himself new things. If he doesn’t understand something, he works at it, figures it out and goes from there. To me, he sometimes seems overloaded, but he just sails right through.”

Whatever the future holds, Pashley says, he and his wife are excited to watch it unfold. “We’ve had a wonderful life,” he says. “Life should be a fun journey, and it has been.”

A Package Deal

When founding Dental College of Georgia Dean Judson C. Hickey began the school in 1969, his aspirations were as lofty as the ever-growing Augusta University skyline. He had precious few resources at hand – the school operated from a trailer and a dirt parking lot for the first three years of its existence – but Hickey had unerring instincts and an inviolable commitment to what really mattered.

One of his top priorities, for instance, was to recruit a faculty with expertise not only in dentistry, but in basic science as well. “Dean Hickey set out to test a hypothesis of teaching,” says Dr. David Pashley, one of the inaugural faculty members. “He said he’d sat through too many dental lectures by physicians who knew nothing about dentistry. He set out to change that.”

He wanted all of his basic science faculty to have not only a dental degree, but a PhD in an area such as physiology, oral biology or pharmacology. Such credentials were few and far between, but he found a wellspring of what he was looking for at the University of Rochester in New York. “There was a group of us who’d all gone to grad school together, then joined the Rochester faculty,” Pashley says. “We were all smart guys, but there was no prima donna. We worked well together and didn’t let egos get in the way.”

Hickey liked what he saw and wanted a package deal. “He came and emptied Rochester out,” Pashley recalls with a laugh.

The faculty were happy to move en masse to a balmier climate and fell instantly in love with Augusta. “It was such a nice change,” Pashley says. “In Rochester, I remember getting a foot of snow on my birthday – on April 24. My wife called it Rotten-chester; she couldn’t wait to get out of there. So Augusta looked awfully good to us.”

The enthusiasm was palpable as the faculty embarked on starting a school from scratch. “The students and faculty had an instant rapport,” Pashley says. “Things really started off with a bang.”

Pashley was among the last of that group to retire; he closed his lab in the Hamilton Wing of the Research and Education Building this spring. But although their numbers have dwindled considerably, their legacy lives on. “Dr. Hickey created just a fantastic school,” Pashley says. “It was a pleasure to be a part of it.”