Study Probes Cause of Periodontal Disease

Dental College of Georgia periodontist is probing a case of hijacking in an attempt to cut the perpetrators off at the pass.

The hijackers are oral bacteria – microorganisms that wreak havoc in the gums, potentially causing tooth loss and even systemic disease.

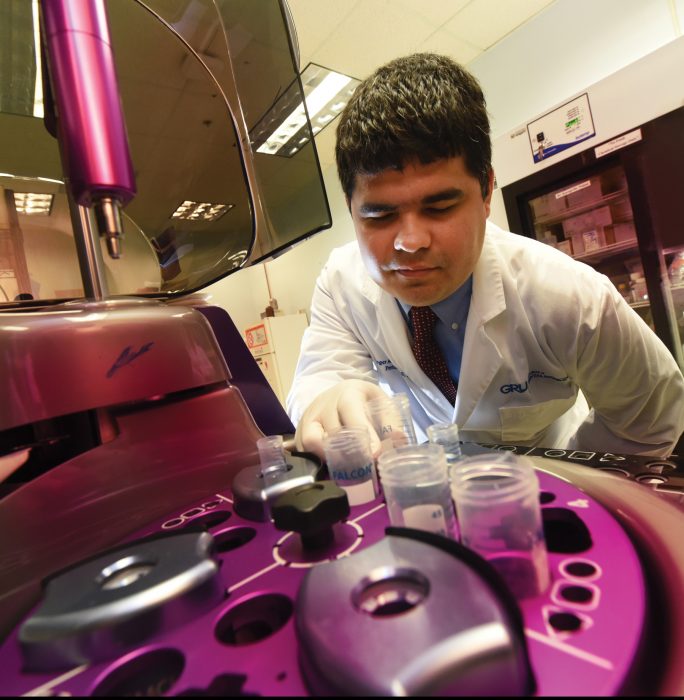

Dr. Roger Arce, an assistant professor of periodontics, is pursuing his theory that the targets of the hijackers are dendritic cells. In a healthy mouth, these cells present antigens – molecules capable of producing an immune response – to signal the immune system to combat the bacteria. But in an unhealthy mouth, these gatekeeping cells seemingly aren’t doing their job.

This enables oral bacteria to run amok – a condition called periodontal disease, which affects almost half of all Americans.

“Dendritic cells are involved in the response to any infection,” said Arce, who earned a dental degree from La Universidad del Valle in his native Colombia, South America, and a PhD in oral biology and a periodontology certificate from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “We think that in the case of periodontal disease, the dendritic cells are prone to be hijacked by oral bacteria. This reprograms the cells to do the bidding of the oral bacteria.”

To put his theory to the test, Arce and his mentor, Dr. Christopher Cutler, chairman of the Department of Periodontics and DCG associate dean of research, use genetically engineered mice depleted of dendritic cells. “This impaired function should give us insight into how the dendritic cells contribute to periodontal disease,” Arce said. “We anticipate the mice will either have less periodontal disease or more aggravated disease.”

The mice offer a telling window into the physiology of humans, he noted. “We know the disease pathogenesis between humans and animals isn’t exactly the same, but our genes are, on average, close to 90 percent the same. We have very similar genetic information. Also, we can specifically deplete genes responsible for the formation of dendritic cells to see the functional outcome, which cannot be done in other biological systems.”

The stakes are higher than the public may realize. “Periodontal disease ultimately affects the tissues that support teeth,” Arce said. “As the bone gets assaulted [by bacteria], teeth start shifting and harboring a lot of bacteria. The final outcome is tooth loss, and the condition may become systemic. For instance, researchers now suspect a link between periodontal and cardiovascular disease.”

U.S. rates of periodontal disease are among the highest in the world, Arce said, citing risk factors including smoking, diabetes and vitamin deficiencies. But Arce suspects a genetic predisposition as well in at least some of those with the disease, and his mice studies should help illuminate the mechanism.

The researchers’ lab, the Periodontal Molecular Immunology Lab, was the first to propose this mechanism in human periodontal disease. “It’s not an exclusive mechanism, but we see it in some humans predisposed to having this condition,” he said.

The research, partially funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research, is a perfect fit both for Arce and the university, he said. “Augusta University offers an environment very conducive to my area of expertise,” he said. “This is a wonderful opportunity.”

And he has high hopes that the study will promptly yield clinical applications. “For the first time in the lab, we’ll be able to experimentally test our hypothesis,” Arce said. “This will enable us to complete the cycle of translational research in the search for future treatment alternatives for periodontal disease in humans. I’m absolutely excited.”

A Stealthy Menace

As prevalent as periodontal disease is in the United States, many people with the condition are blissfully – yet dangerously – unaware that they have it. Symptoms, which are somewhat vague and relatively easy to miss, include reddened, swollen and/or bleeding gums. But only a dentist can definitively diagnose it. “X-rays and clinical exams are needed for a diagnosis, so it’s important to see your dentist regularly,” said Dr. Roger Arce, a Dental College of Georgia periodontist. In addition to regular dental checkups, Arce advices regular brushing and flossing, along with a smoke-free and otherwise healthy lifestyle. “Diet may play a role, especially when it comes to the lack of vitamins,” he said. The disease is treated by local debridement of infection, sometimes in combination with systemic antibiotics. “But we can’t cure this disease, only arrest it,” Arce stressed, adding that he hopes research like his will pave the way toward better treatment and ideally even prevention.