The only physician in Gray, Georgia, for about 35 years, Dr. H.B. Jones never forgot his roots or the medical school that made his life possible.

This lady had walked from the grocery store down there into the street and didn’t see the car coming. She was terribly, terribly injured — dying really. And Dr. Jones was right behind her, and he got out and did everything he could until the ambulance came from Macon. She did not make it. But I remember Aunt Mae said it really upset him that he couldn’t get her to live.”

– Marilyn Sauls

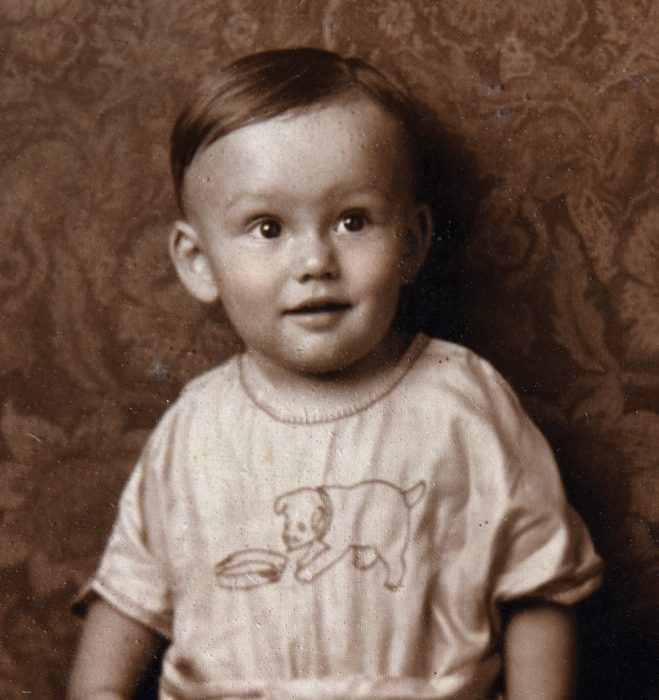

Henry Berner Jones Jr., ’50, was born in Gray, Georgia, on May 9, 1927, but his birth would be one of the only times family and friends would use his full name. To his family, he was always H.B., and then later, Dr. Jones. “That’s just what you did,” said second cousin Danny Greene with a laugh. “He didn’t tell you that you had to call him that … He just commanded the respect of folks, even family members.” Even his mother, Lutie Mae Greene Jones, was only heard publicly to refer to him as “The Doctor” in his adult life.

Lutie Mae and her husband, Henry Berner Jones Sr., would divorce when H.B. was just 2 years old. The young mother, one of a family of 12, didn’t go far: She moved back home to the sprawling white-framed house where she grew up and worked as a postal clerk at the Gray P.O. and also took in sewing to make ends meet.

As an only child to a single mother, it’s no surprise that Lutie Mae and her young son were very close. “His mother supported him, and he supported his mother,” said Greene’s sister Nancy Nash. “It was that family of two.” And it’s likely her example of hard work that influenced him all throughout his life. Even as a child, “he was always very studious,” said his first cousin Janelle Bridges, who says Dr. Jones was like a brother to her.

It was also the Great Depression. “It was very hard,” said Bridges’ sister Marilyn Sauls, who remembers those frugal days well. H.B. had a paper route and also pumped gas as a teenager to help make ends meet — “although I can’t picture Dr. Jones pumping gas,” laughed Greene. “But you had to do what you had to do,” said Lynn Nelson, who along with her husband, Brick, were Dr. Jones’ business associates and friends.

He had come off his paper route and came in and found his grandmother. He came up to our house and said, ‘Grandmother’s sick, come.’ Then Mother took me and Janelle down there to see what had happened. He had come in and thought she was playing a trick on him, that she was [pretending to be] asleep and wouldn’t wake up. I’ll never forget that picture as long as I live. Maybe that sparked [his] medical interest.

– Marilyn Sauls

‘The Only Way He Could Have Become a Doctor’

The solemn little boy grew up to be a slim, serious teenager sporting round glasses and a neatly combed hairstyle, part of the class of ’44 at the new Gray High School. According to Greene, “One of his teachers wrote to him in later years to recognize him for his ‘wonderful brain and temperament for humanity.’ She also declared that she knew he possessed what ‘only a few are given — mentality and humility.’” Although the high school offered a strong curriculum of English, history, literature and social sciences, its weak-nesses were math, the natural sciences, chemistry and biology. But it also had teacher Louise Morton, who took it upon herself to study the sciences so she could mentor students who wanted to go further in those fields. One of those was H.B. “He told me so many times — and Janelle too — that that’s the only reason he could have become a doctor is because he got the science and the math from what Mrs. Morton had studied,” said Sauls.

At only 17, H.B. enrolled at Emory University’s Junior College at Oxford — and Nash points out that he was one of the first of the Greene family to extend his education beyond high school. He continued to pursue science while he was there, sticking to the university’s rigorous study schedule of 7:30 a.m. to 11:30 p.m. for six and one-half days a week. But the self-described bookworm still managed to cut loose, at least on Saturday afternoons. He and fellow students would each pay 10 cents to pile into a taxi headed for downtown Covington, two in front and nine in back, where they would hang out at the local drugstore or catch the latest movie. His family isn’t sure why H.B. chose the Medical College of Georgia to further his growing interest in medicine. It may have been its convenience to his hometown — just about two hours away by car — or the cost may have appealed to his frugal nature. An internship at Macon Hospital (now Navicent Health) followed, before H.B. was assigned to Alaska during the 31 months that he served in the medical corps of the U.S. Air Force during the Korean conflict. He wrote to his mother often during those months, asking about his uncles and aunts, talking about the cold and how the wind blew all the time, but there wasn’t much snow. The time spent in an environment so different from the balmy South likely gave him a love of seeing new places, one that he wouldn’t be able to indulge again until after he retired.

He came back to his roots. Jones County needed a doctor when Dr. Zachary died. And it may be as simple as this is where his mother was. I felt like he looked after his mother and he had a commitment to the community. And he had the support of his family — he could come back and practice on his own relatives and have a good practice!

– Janelle Bridges

A Return to His Roots

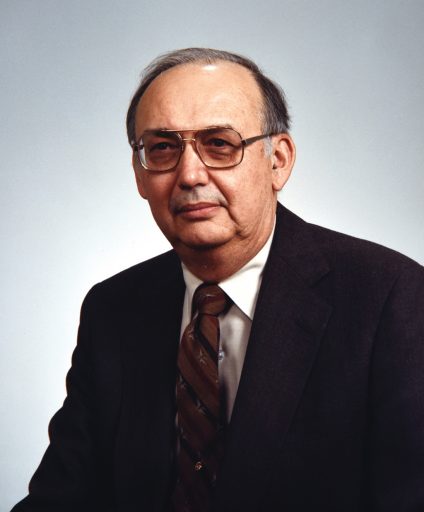

According to Greene, older physicians at Macon Hospital always remarked, “Oh, yes, Dr. Jones — I always wondered why he never started practicing at the hospital.”

“And they would refer to him as an excellent diagnostician. If he had wanted to take the opportunity to practice somewhere else, a bigger practice, bigger town, hospital practice, that kind of thing, he had that opportunity, but yet he came back to Gray to practice where he came from,” said Greene. “That was pretty unselfish of him.”

As the only physician in his hometown, Dr. Jones covered the lifespan of his fellow citizens for about 35 years, doing everything from pediatrics and geriatrics to minor surgery and even X-rays, which he read himself. He made house calls, usually in the latest-model car — of which he maintained two, just in case one wouldn’t crank up. And he saved the lives of at least two family members and likely others during emergencies, one from an accidental gunshot in the stomach and the other from a life-threatening reaction to a yellow jacket sting. “He was the true definition of a country doctor,” said Brick Nelson — “but he wasn’t country,” added his wife, Lynn. “He would take care of you if he could, but he knew also when you needed to go somewhere else and he knew right where to send you,” said Nash.

And quiet? Yes, the doctor was still the studious boy in many ways. “He had the worst bedside manner,” said Brick Nelson with a laugh. Added Nash: “I can just recall going in and sitting there. Here’s his desk and here’s the chair beside his desk. He’s sitting there and you’re talking to him, and he says, ‘Well, what’s going on?’ and then you tell him and he’s nodding and he’s writing and he’s nodding and listening, and then his famous line — ‘I suspect.’ That was his line … and then he might reach for that prescription pad, and with that fountain pen — a real fountain pen, never a ballpoint pen — he might start writing a prescription, and as he writes it, he’s telling you, well, take this, try this, we’re going to do this for a certain amount of time.”

“He was very explicit with his directions,” said Greene, “and as he made his decisions, very thoughtful, very methodical” — “not chatty,” agreed Nash.

“But he was very compassionate, very kind, too,” added his cousins. “And people had confidence in him.”

Patients, family and friends — he maintained close ties to several of his fellow students from MCG — liked to try to make him chuckle. “About him being so quiet, I never heard him laugh outright, but he had a chuckle,” said Nash. “A smile and a chuckle, and you knew then that, ah, got him.”

His chuckle was in full view of the whole town of Gray one night when he and other local men put on a “Womanless Wedding” as a fundraiser for the Kiwanis Club sometime in the late ’50s. The phenomenon has its roots in the South, according to a story by National Public Radio, beginning in the 1920s, where men would dress up to play all the parts of the wedding party, including the bride, bridesmaids, flower girls and mother of the bride, taking care to “ham it up, kissing audience members of both genders, flashing garter belts, adjusting whatever passed as breasts and, in general, just being naughty,” wrote historian Craig Thompson Friend in his 2009 book Southern Masculinity.

“Dr. Jones put on a dress and he couldn’t have worn his mother’s dress because he was tall and his mother was so small, but I remember it being a pink dress, but he had on one of his mother’s little hats,” said Danny Greene. “And our father, who was in the wedding also … came by Dr. Jones and pretended to fall down, and as he fell down, he had a pair of pink bloomers in his purse, and he threw them up in the air because it looked like he had fallen and lost his pants, but they came back down and landed on Dr. Jones’ head. So he sat there with those pink bloomers on his head, and his shoulders just shook. No response, other than his shoulders shook and he smiled and that little chuckle that he did.

“That was just so out of character for him, it was like, ‘That’s Dr. Jones?’”

He didn’t quit practicing until there was another doctor in town. He kept on until there was a replacement … he would not have deserted the ship under any circumstance.

– Brick and Lynn Nelson

Celebrating Dr. Jones

Roughly 40 years after his graduation from medical school, at his retirement in 1991, his cousins Janelle Bridges and Marilyn Sauls threw him one of the largest parties ever in Gray and its surrounding areas. A big to-do was also out-of-character for Dr. Jones — “but he just reveled in it,” said Brick Nelson. “There must have been lord knows how many people there. Y’all put a nice big chair out there for him and he sat in the chair and people came with greetings. And it just stunned me about him because he was so quiet and apparently introverted and unassuming, yet he just loved that big retirement party. Everybody in Jones County turned out, and he put a Band-Aid on almost all of them.”

After retirement, Dr. Jones took the opportunity to travel once again, booking tours all around the world, no doubt seeing the sights he used to watch on TV and record on his VCR. But he’d still often be seen at locations in Gray like the local P.O., where there would be a bit of conversation: “Good to see you, Dr. Jones,” and “Thank you, good to see you, too.”

Near the end of his life, Dr. Jones suffered from heart problems and finally congestive heart failure. “He knew exactly what was wrong with him,” said Bridges. Added Greene, “He had already diagnosed himself.”

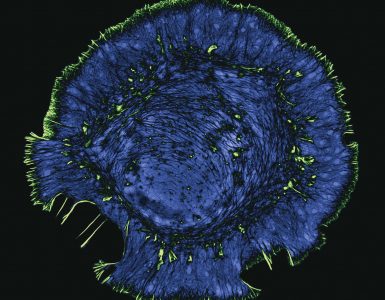

Dr. Jones passed away on Jan. 14, 2011, at the hospital where he interned, with his family surrounding him. Six years after he passed, it was discovered that he had left a bequest to his alma mater, which will be used to support stroke and dementia in the MCG Department of Neurology. “I think it goes back to the appreciation,” said Nash. “Appreciation for the education and what it allowed him to do for the rest of his life,” said Greene. Being raised not particularly affluent — because that was the Depression era and his mother worked very hard and he worked — and I just think that he appreciated the education he got to afford him the things he really wanted in life and the lifestyle that he enjoyed.”

“We talked about him being married to his practice, to the field of medicine. And the medical college provided all of that,” said Brick Nelson.

“We were fortunate to have him,” said Lynn. “And I think Dr. Jones enjoyed his life, I really do.”