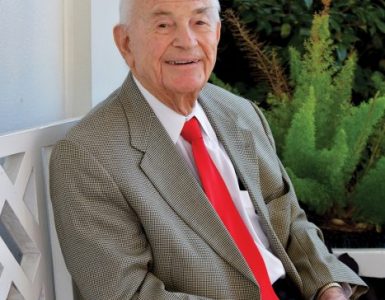

MCG’s third black student takes pride in where he has gone — and in coming back.

He would like to have seen that statistical analysis.

He would like to have seen that statistical analysis. His medical school class of 106 students had six Jews and one black, and they all ended up working on the same cadaver team in anatomy his freshman year.

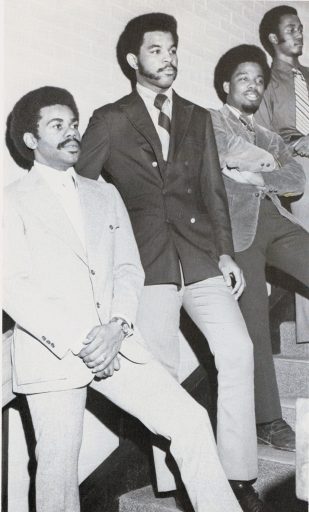

“They said it was random selection,” says Dr. Tommy Leonard Jr., a 1973 graduate of the Medical College of Georgia and the third black student to call Georgia’s public medical school his alma mater.

MCG was really his first venture into essentially an all-white environment. Leonard had gone to a black high school in his Columbus, Georgia, hometown, then to historic and historically black Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, founded by freed slave Booker T. Washington and home of the Tuskegee Airmen, the first black pilots in the U.S. Air Force.

At medical school, his predecessors, Drs. Frank Rumph and John T. Harper Sr., Class of 1971, had broken ground as the first two black students, for which Leonard is forever grateful. Still, while the affable young man was just not 100 percent sure what to expect, he did expect hostility.

What he primarily found was isolation, sometimes in seemingly small things that still loomed large. Like the tradition for students to go to the local pub called Squeaky’s after an exam. “I was never invited to Squeaky’s,” he says of the nearby hangout, long boarded up but still standing on nearby Central Avenue.

“I felt that if I did the work, passed the tests, acted forthright and as a gentleman, that I would eventually finish and that is what I tried to do,” Leonard says. But it did hurt this gentle man who would choose to care for fragile newborns and appears most comfortable with a smile on his face and in his heart.

Hardly Random Selection

Trailblazing and medicine were reasonable choices for him, certainly more than random selection. His father, Tommy Leonard Sr., had a seventh-grade education but excelled in his 30 years in the military, including serving in the original predominantly black 24th Infantry Regiment. The younger Leonard, who spent 28 years in the military himself and retired as a colonel, shares the interesting insight that dad was always somewhat disappointed that son chose to be a doctor. “He said I went to medical school to get out of working,” he says, this time without his customary smile. But dad also inspired son, both by his commitment to his country and by his bragging about his smart son at the local barbershop.

His mother, Ersa Colquitt Leonard, and father had married late in life; she was 35 and he was 50. Father Leonard, an only child, and mother Leonard, the oldest of six children, had been busy before helping to care for the families they were born into. Mother was a licensed practical nurse working in pediatrics. She would come home late at night from her civilian position at The Station Hospital (now Martin Army Community Hospital) at Fort Benning, Georgia, and tell her eldest that they had lost another baby.

“I didn’t like to see her so sad,” he says. She called them “blue babies,” which also piqued his interest; science and physiology classes at Spencer High School fueled it. So did his five-feet-and-fit science teacher Del Marie Vernon. In his first class with her, this teacher who never batted an eye staring up at bulky football players, gave Leonard a “D.” He whined that he was the smartest kid in her class.

“She said, ‘You are still not working up to your potential,’ and boom, she got my attention,” he says. “She is not grading me on how I compared with other kids. She is grading me on what she sees in me. That was good for me. I needed that. It changed me.” The further fired-up student never gave Vernon another lick of trouble. In fact, he went to catch up with her just last year in his hometown.

Rather Choice and Success in Saving Babies’ Lives

While his cadaver team was hardly a representative sample of the Class of 1973, it turned out to be a great one. Dr. Aaron S. “Chico” Goldberg and Dr. Bruce R. Mirvis were among those who shared Leonard’s first patient. The three would become fast friends who could and would talk about anything, even eventually joke about race as a way to diffuse the sensitive subject.

They would all also choose pediatrics and be chosen again by MCG. Dr. Alex Robertson, who served nearly a decade as chair of pediatrics starting in 1972, recruited the trio to stay on for at least their pediatric internship. Leonard would work with greats like Dr. William B. Strong, longtime chief of pediatric cardiology who, with Dr. Maurice Levy, would later co-found the Georgia Prevention Institute, an early and lasting force in how to help children grow up to be healthy adults.

Leonard definitely fell in love with pediatrics that year. His closest classmates would stay at MCG to complete their residency, but Leonard, namesake of the U.S. Army lifer and already in the U.S. Army Training Reserve at Tuskegee, entered the armed services instead. He completed two years as a general medical officer first in Korea then Missouri before going back to residency.

He did his pediatric residency at Brooke Army Medical Center and neonatal-perinatal fellowship at Tripler Army Medical Center. He then served as chief of Neonatal Services at William Beaumont Army Medical Center in El Paso and the 97th General Hospital in Frankfurt, Germany, and worked for a time where his mother worked at Martin Army Community Hospital back home in Columbus. Leonard would stay in his hometown for six more years in both a solo and group practice.

In 2000, he got a call from Dr. Leonard Weisman, who then headed the Baylor College of Medicine Section of Neonatology. The two had crossed paths in the military, and Weisman was just starting an innovative program that would put neonatologists out in the massive Houston community to help ensure that all babies get the highest level of care within their first few minutes of life.

The opportunity to be the first neonatologist on the community ground was enough to lure Leonard out of his hometown. The initiative would be most important of course to help ensure that the 1 percent of premature or otherwise ill newborns were optimally managed and transported to a level III or IV nursery like the program at Texas Children’s Hospital, the country’s largest pediatric hospital and the primary pediatric training site for Baylor.

“What we were trying to do was reach out to community hospitals, to put neonatologists in those hospitals so that we would be able to bring that expertise to bear in the first few critical minutes,” says Leonard. “I was the ground floor.” Seventeen years later, Texas Children’s Community Initiative includes a dozen community hospitals caring for 23,000 infants annually.

Today, Leonard’s 40 years of experience packaged with his friendly demeanor have made him a logical choice for making the first visits to a new hospital. At the moment, his role in the initiative is as medical director of Nurseries, Neonatology and Pediatrics at The Methodist Hospital, another large hospital with academic affiliations with Weill Cornell Medical College and New York Presbyterian Hospital. The hospital’s extensive clinical and research activities include areas like cancer, transplant, neurology and neurosurgery, but like other program participants, the hospital would not have neonatologists in house without the initiative started by Weisman.

Leonard acknowledges that there is some kind of magic in babies who need care, like the ones his mother told him about on those nights long ago. There is also magic in talking with parents whose babies are doing just fine. He also happily confesses that he is one of those people who considers his work a pleasure. Coming up on his 70th birthday this August, he is cutting back a bit, mainly on the night call that takes an increasing toll.

And a Call From his Medical Home

In 2016, he got a call from his medical school. Leonard had not been back to MCG since he finished his internship in 1974. Still he carried it with him. He has always been proud of MCG, of how the classic skull and crossbones ring he wears is recognizable in whatever medical circles he travels. “You can’t see this ring and not know where a person is from. I loved it so much I had diamonds put in the eyes,” he says, then characteristically laughs. Proud of how, no matter what the medical circle, his medical education prepared him professionally to be a good, caring physician.

The call was from Dr. Joseph Hobbs, who graduated from MCG the same year Leonard left it. Hobbs was inviting him to be a special guest at the inaugural event commemorating the 50th anniversary of MCG’s desegregation.

“It feels good,” he said that Feb. 7 back on campus, then repeats the succinct assessment. “Even the ride from the airport. I took a walk along the Riverwalk, it being very similar to my home, Columbus, Georgia, along the Chattahoochee River versus the Savannah River. But it felt good.”

He had mostly avoided looking back on how the isolation had affected him. But the event gave him pause to reflect and to acknowledge the long-standing pain … and to heal.

“I never felt like I was part of the school; does that make sense?” he says. “I was tolerated, I graduated, I left. I wondered what my white counterparts felt. Did they feel that joy, kind of like when you graduate from college that this was your alma mater? I didn’t feel that joy. I felt that I had achieved and graduated, but I did not feel that joy.”

Then he came home.

“Everybody wants to be accepted. I wanted to be accepted then. I wanted to be recognized now, and hear ‘Welcome home, Tommy. We really appreciated you when you were here, and we are glad to see you have done well, as Frank did well … and as John did well.’ That is why today I am happy to be back here. I had my misgivings, I had all those little feelings, but I have always had a love.”

Leonard makes the life analogy of a girlfriend that you love a lot who does not quite reciprocate. His return and subsequent reconnections with his medical school made him realize that certainly, thankfully, she now does.

Not too many days after getting back home to Texas, Leonard signed up to be a lifetime member of the MCG Alumni Association.