Sugar Coat It: Sugar coating on our cells is hardly icing. Rather, it is essential to cell health and ours.

Now, scientists have also developed a way to identify biomarkers for a wide range of diseases by assessing antibodies to the complex sugars coating our cells.

The new, highly sensitive Luminex Multiplex Glycan Array enables the kind of volume needed to establish associations between antibody levels in our blood to these complex sugars, or glycans, and conditions from cancer to autoimmune disease and dementia, they report in the journal Nature Communications.

Like our cells, the beads in the new array are sugar coated. By exposing patient blood or serum to them, the scientists can see which glycans the patient is making antibodies against and how much they are making, looking for trends that could predict disease course, even potentially one day diagnose their disease.

In fact, the scientific team led by Dr. Jin-Xiong She, director of the Center for Biotechnology and Genomic Medicine at the Medical College of Georgia and Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar in Genomic Medicine, has already used the array to identify a potential biomarker for high risk of ovarian cancer relapse following surgery and standard chemotherapy regimens.

“While we think this new test will eventually enable us to do many things, right now we have evidence it can help determine biomarkers for those at risk for relapse from cancer,” says She, corresponding author of the published study.

“With this new technology, we can explore what is normal and what is disease. This is just the beginning.”

She is also principal investigator on a new $1.6 million grant from the National Institutes of Health that is enabling another significant expansion in both the volume of patient samples and glycans the array can handle. The scientists also are beginning to make their array available to other investigators, including providing ready-made glycan beads for use in their labs.

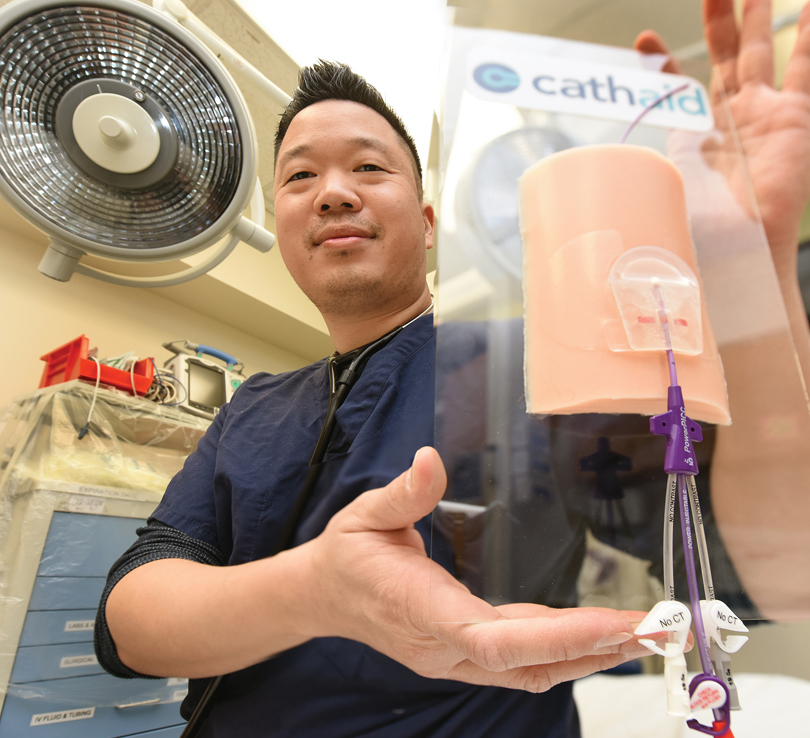

An Easy Catheter Fix: Dr. George Hsu, a third-year emergency medicine fellow at MCG, is the recipient of a 2018 Innovation Award from Georgia Bio, presented to individuals who are forging new ground by thinking outside the traditional paradigms to create unique technology.

Hsu worked with former Georgia Institute of Technology classmates to develop a device called Cathaid to address unfortunate but common complications of medical treatment: catheter-associated infections and unintentional positional catheter shifts. Both are a major source of morbidity and mortality for patients. In certain settings, a quarter of medical catheters will experience some form of complication putting them at risk for failure, Hsu says.

“Health care systems spend hundreds of millions of dollars to try and prevent these issues, and even with current best practices, they still happen,” he says.

Their device is a cover that is immediately applied after a catheter is inserted. Its securement mechanism, which functions almost like a lock and key, fastens the catheter in place with an antimicrobial medical-grade adhesive to help stave off infections. Cathaid also has a small window with a colored strip that crosses the device and the catheter. Called a positional verification system, if the catheter portion of the strip has shifted, it can indicate – in real time and to any member of a patient’s care team – that the catheter has moved.

“If they shift, even just a few millimeters, it can be catastrophic,” Hsu, who also serves as CEO for Cathaid, says. “Catheter shifts are usually detected when patients decompensate or the medications and fluids that are going through the catheter get backed up. Typically those things happen over hours and days. This device could detect them immediately.”

Hsu and his collaborators are working with the Advanced Technology Development Center, a startup incubator at Georgia Tech that helps technology entrepreneurs in Georgia launch and build successful companies. Their hope is to have Cathaid on the market and in hospitals this year.

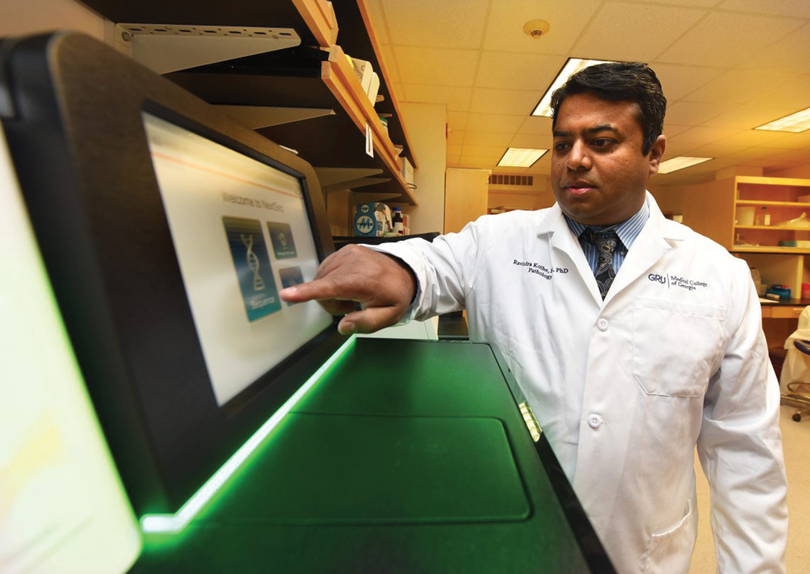

Improving leukemia outcomes: Patients diagnosed with the most common form of leukemia who also have high levels of an enzyme known to suppress the immune system are most likely to die early, researchers say.

High levels of this enzyme, indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase, or IDO, at diagnosis also identify those who might benefit most by taking an IDO inhibitor along with their standard therapy, they report in the Nature journal Scientific Reports.

“We want to help people who are not responding to treatment and are dying very soon after their diagnosis,” said Dr. Ravindra Kolhe, corresponding author, breast and molecular pathologist and director of the Georgia Esoteric & Molecular Labs LLC in the MCG Department of Pathology.

A review of 40 patients with acute myeloid leukemia, or AML, found increased IDO expression in the bone marrow biopsy, performed to diagnose their disease, correlated with lower overall survival rates and early mortality.

It also indicates that IDO expression should routinely be measured when the diagnostic bone marrow biopsy is performed, Kolhe says.

An early phase clinical study already is underway to begin to explore the IDO inhibitor’s clinical potential in these patients. Sites include the Georgia Cancer Center at MCG as well as Johns Hopkins University and the University of Maryland Schools of Medicine. Biopharmaceutical company NewLinks Genetics, who produces the inhibitor Indoximod, is funding the study.

While everyone has the IDO gene, it’s the cancer cells in this scenario that activate the disabler of the immune response, which is also used by the fetus and solid tumors, he says.

Stem cells in the bone marrow are supposed to mature into a variety of cells that enable our blood and immune system function. Instead in AML, stem cells get stuck in an in-between, undifferentiated state called blasts.

“It’s very normal to go to the blast step, providing it matures from there,” Kolhe says. “In leukemia, stem cells get limboed in the blast state so you don’t get any maturation. That means there are low platelets so you get clotting problems, you have low neutrophils so you have infections, you have less red blood cells so you get anemic,” he says.

In fact, bleeding is a major cause of death for patients and often, significant gum bleeding is the first indicator.

The MCG researcher found one thing the blasts are producing is IDO.

“The patients who died at six months had a high expression of IDO while the blasts produced relatively little IDO in the patients who lived five years or more,” Kolhe says. “Right now we know it’s high in patients who die at six months and we show that it’s an independent indicator if you adjust for other known variables.”

Another Reason to Reduce Antibiotic Overuse: Antibiotic use is known to have a near-immediate impact on our gut microbiota, and long-term use may leave us drug resistant and vulnerable to infection.

Now there is mounting laboratory evidence that in the increasingly complex, targeted treatment of cancer, judicious use of antibiotics also is needed to ensure these infection fighters don’t have the unintended consequence of also hampering cancer treatment, scientists report.

Dr. Gang Zhou, immunologist at the Georgia Cancer Center and the MCG Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and Dr. Locke Bryan, hematologist/oncologist at the Georgia Cancer Center and MCG are both co-authors of the study published in the journal Oncotarget. Together with their colleagues, they have some of the first evidence that in the high-stakes arena of cancer, where chemotherapy is increasingly packaged with newer immunotherapies, antibiotics’ impact on the microbiota can mean that T cells, key players of the immune response, are less effective and some therapies might be too.

They report that antibiotic use appears to have a mixed impact on an emerging immunotherapy called adoptive T-cell therapy, in which a patient’s T cells are altered in a variety of ways to better fight cancer. However, they found that one of the newest of these – CAR T-cell therapy – is not affected by antibiotics, likely because it is not so reliant on the innate immune system.

Human studies are needed to see whether antibiotics affect the outcomes of adoptive T-cell therapy and to give clinicians and their patients better information about how best to maneuver treatment, Zhou notes.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health and an American Cancer Society Research Scholar Grant.

Not Just for Baking: A daily dose of baking soda may help reduce the destructive inflammation of autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, scientists say.

They have some of the first evidence of how the cheap, over-the-counter antacid can encourage our spleen to promote instead an anti-inflammatory environment that could be therapeutic in the face of inflammatory disease, MCG scientists report in The Journal of Immunology.

They have shown that when rats or healthy people drink a solution of baking soda, or sodium bicarbonate, it becomes a trigger for the stomach to make more acid to digest the next meal and for little-studied mesothelial cells sitting on the spleen to tell the fist-sized organ that there’s no need to mount a protective immune response.

“It’s most likely a hamburger, not a bacterial infection” is basically the message, says Dr. Paul O’Connor, renal physiologist in the Department of Physiology and the study’s corresponding author.

In the spleen, as well as the blood and kidneys, they found after drinking water with baking soda for two weeks, the population of immune cells called macrophages, shifted from primarily those that promote inflammation, called M1, to those that reduce it, called M2. Macrophages, perhaps best known for their ability to consume garbage in the body like debris from injured or dead cells, are early arrivers to a call for an immune response.

“You are not really turning anything off or on, you are just pushing it toward one side by giving an anti-inflammatory stimulus,” O’Connor says, in this case, away from harmful inflammation. “It’s potentially a really safe way to treat inflammatory disease.”

Vitamin D’s Role in Heart Health: More than 80 percent of Americans, the majority of whom spend their days indoors, have a vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency that researchers say could be impacting heart health.

In what appears to be the first randomized trial of its kind, they found that arterial stiffness was improved in just four months by high doses of vitamin D supplementation in young, overweight/obese, vitamin-deficient but otherwise still healthy African-Americans, they write in the journal PLOS ONE.

Overweight/obese blacks are at increased risk for vitamin D deficiency because darker skin absorbs less sunlight – the skin makes vitamin D in response to sun exposure – and fat tends to sequester vitamin D for no apparent purpose, says Dr. Yanbin Dong, geneticist and cardiologist at MCG’s Georgia Prevention Institute and the study’s corresponding author.

Participants taking 4,000 international units – more than six times the daily 600 IUs the Institute of Medicine currently recommends for most adults and children – received the most benefit, says Dr. Anas Raed, research resident in the MCG Department of Medicine and the study’s first author.

That dose, now considered the highest, safe upper dose of the vitamin by the Institute of Medicine, reduced arterial stiffness the most and the fastest: 10.4 percent in four months. “It significantly and rapidly reduced stiffness,” Raed says.

Two thousand IUs decreased stiffness by 2 percent in that timeframe. At 600 IUs, arterial stiffness actually increased slightly – .1 percent – and the placebo group experienced a 2.3 percent increase in arterial stiffness over the timeframe.

While heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, blacks have higher rates of cardiovascular disease and death than whites and the disease tends to occur earlier in life.

A broken master clock is bad news for blood vessels: What do bad sleep habits and stiff blood vessels have in common?

Nothing good, say MCG scientists exploring what appears to be a direct connection between a circadian clock that isn’t working as it should and an enzyme that promotes inflammation working overtime.

The connection appears to be between Bmal1, a transcrip-tion factor that senses light and drives our master circadian clock, and ADAM17, an enzyme that sets inflammation-producing proteins free from our cells to target and thicken our blood vessel walls.

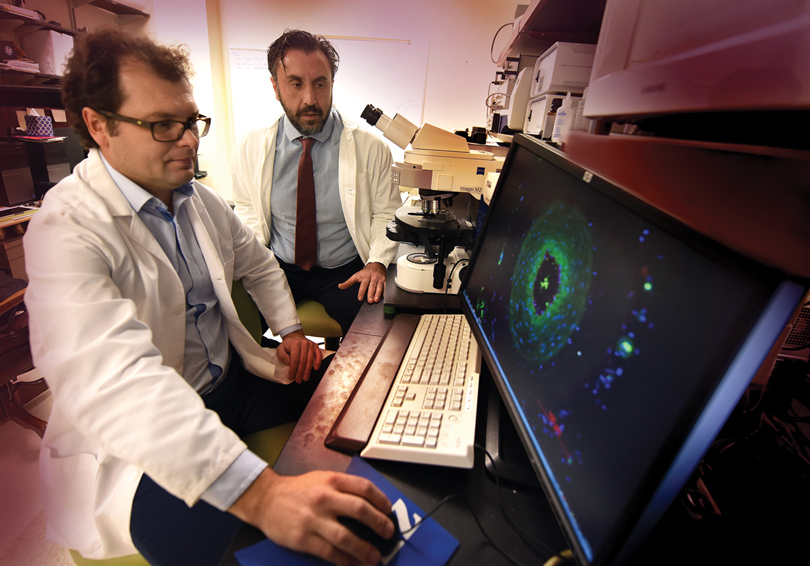

The scientists, both vascular biologists, are Dr. Dan Rudic, who studies the circadian rhythm that drives our sleep-wake cycle, and Dr. Zsolt Bagi, who made the connection between ADAM17 and stiff blood vessels.

Now they want to know, “Is it a direct connection?” says Rudic, who is thinking that Bmal1 may directly regulate ADAM17.

He and Bagi are co-principal investigators on a $2.2 million National Institutes of Health grant that is enabling them to explore the unhealthy relationship, with the goal of also identifying the best point to intervene.

Rudic’s lab is among those that have seen the impact of a disrupted circadian rhythm on blood vessels. Mice without normal Bmal1 function have stiff blood vessels, age rapidly and die early. It essentially cuts their life span in half, from two years to one, and could potentially do the same in humans, Rudic says.

“Stiff blood vessels are probably one of the best surrogates of aging other than death,” he says.

In human tissue, Bagi has connected stiff blood vessels to high levels of ADAM17 and low levels of its natural inhibitor. He has watched the inflammation-producing proteins ADAM17 sets free into the bloodstream make a beeline for the heart, where they thicken and stiffen the walls of the tiny blood vessels that help feed the important muscle. Bagi’s team found the same relationship in mice that they found in human blood vessels.

They wondered if these two causes of stiff blood vessels were connected. In fact, is the relationship between the two the primary mechanisms of action for a messed-up circadian clock causing stiff blood vessels?

They have early evidence that downregulation of the primary clock – which naturally occurs with aging as well as habits like sleeping fewer than five hours nightly, even from regularly consuming too much caffeine – prompts the unhealthy increase in ADAM17. “This is a novel and largely unexplored signal,” Rudic says.

He and Rudic are looking at clock dysfunction and ADAM17 from many angles to answer questions like whether bringing down levels of ADAM17 reduces the stiffness associated with clock dysfunction. Bagi is working again with dysfunctional human blood vessels, using biochemical assays to this time also look at clock gene expression. “You get a footprint of what was,” says Bagi, of the now disconnected blood vessels. Preliminary data indicates Bmal1 is down in this scenario, Bagi says.