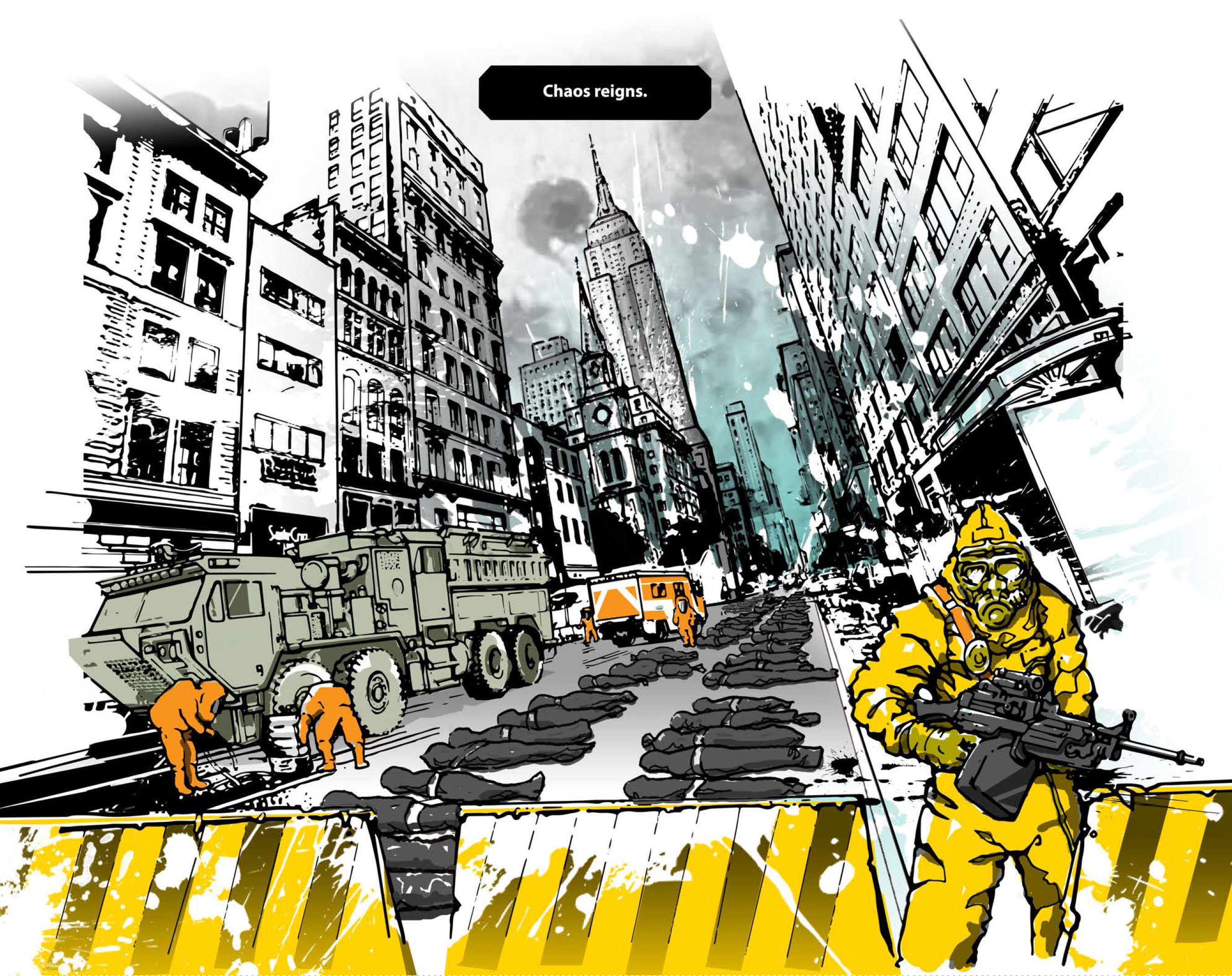

The West Coast wakes to the news: New York City is gone.

Exploiting a flaw in the city’s cargo inspection hardware, state-sponsored terrorists smuggled a dirty bomb through Brooklyn’s Red Hook port. Casualties number in the millions. In the span of a few breaths, the most populous city in America has been reduced to ash and echoes. Answers are sparse.

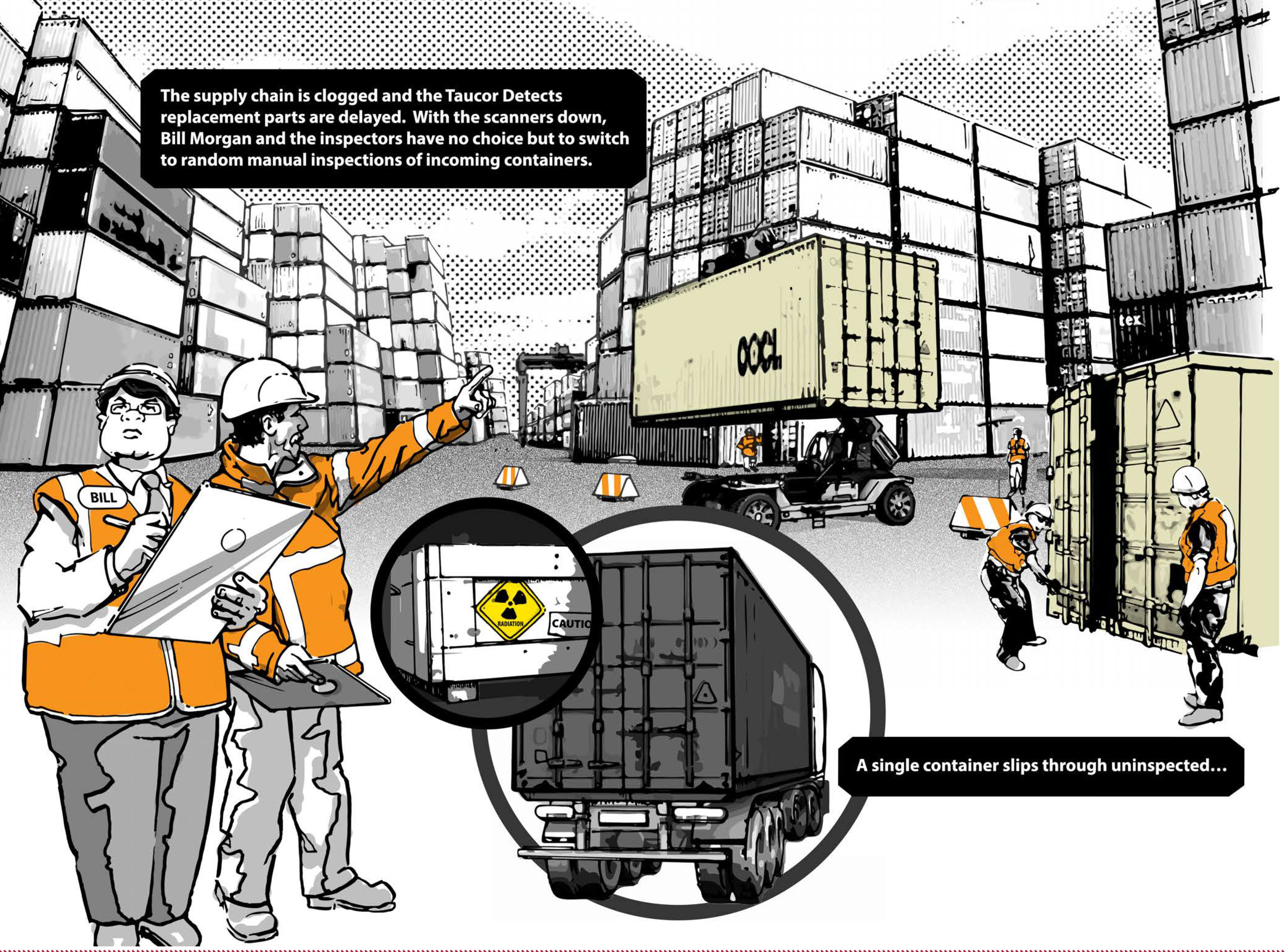

The attackers’ country of origin remains a mystery, but the path they took is clear. After using targeted spearphishing emails to gain access to the city’s automated supply chain, they used a bot-net to hack into millions of internet of things devices. Placing orders for fresh fruit and milk, they then waited as thousands of automated delivery drones took to the seas, skies and streets to meet the sudden demand. Meanwhile, dockworkers at Red Hook, frustrated with their malfunctioning equipment, switched to random manual inspections to make up for the delay. Hackers learned of the change in procedure at the dock by scouring the social media feeds of a dockworker named Bill Morgan. Now deceased, Morgan gave them everything they needed with one disgruntled tweet.

None of this ever happened, of course. It’s just a story; a fictional account of things that have not and might never come to pass. Like all good stories about the future, though, there’s a hint of truth to it.

Brian David Johnson, director of the Threatcasing Lab at Arizona State University (ASU), has made a career out of finding the truth in stories like this one. Pioneers in the emerging field of futurism, he and his colleagues at the School for the Future of Innovation in Society do the unthinkable. They write the future.

Or rather, they write potential versions of it.

Despite that distinction, Johnson is quick to point out he’s no Nostradamus.

“We’re not predicting the future,” Johnson said. “What we are doing is using a broad range of disparate inputs from many areas — social science, technology, economics, cultural history — and expert interviews to model possible futures, positive and negative.”

Johnson frequently works with groups of experts to put together something called “futurecasting sessions.” In these sessions, he and his colleagues try to imagine what effects new and innovative ideas might have on our future. Once the group has a shared vision (or shared story) to build from, the real work begins: Finding ways to make the positive effects a reality while preventing the negative ones from ever happening. The trick is to find balance, and in so doing, truth. But it’s easier said than done, given the distance between the two extremes.

“We have to be able to take both of those ideas in,” Johnson said. “That’s one of the hardest things for my students to do, is to be able to hold two opposing ideas in their heads about the future, and to understand that they are both somewhat true.”

As a business strategy, imagining the future is undeniably useful. So much so that Intel hired Johnson in 2009 to help envision some of its own future products. But the private sector isn’t the only place you’ll find futurists like Johnson. Organizations like the U.S. Air Force Academy and the Army Cyber Institute frequently seek out his expertise on “threatcasting,” a variation of futurecasting he developed in 2011. Since then, Johnson has written a number of threatcasting scenarios. Many have been published in the form of “science fiction prototypes” (SFPs).

The story about New York is one of Johnson’s — a snapshot from an SFP titled, “Two Days After Tuesday.”

Based on research from the Army Cyber Institute and ASU, “Two Days” is at its core a statement about the dangers of phishing. It was developed during a threatcasting scenario, and the final product, presented as a stylized sci-fi graphic novel, is available free online. The choice of format was deliberate. Johnson, along with organizations like Cisco Hyper-Innovation Learning Labs, which produced “Two Days,” have, in that sense, seen the future. And the future is absorbed through popular media.

“That’s why we use things like comic books, we use things like the free press,” Johnson said. “We’re trying to come up with tools for the broader public.”

Historically speaking, there’s no better way to reach that same public than through science fiction. The proof lies at the very core of the Information Age. Technological advances like those of ’60s and ’70s were largely (and unambiguously) inspired by tales from the Golden Age of Sci-fi. The faster-than-light ships of Star Wars and tricorder communicators of Star Trek, not to mention the rocket-and-robot-filled writings of great thinkers like Ray Bradbury, Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov, gave people hope. In a time when most of the world was teaching its children to hide under desks for fear of thermonuclear war, sci-fi’s visionaries were encouraging them to turn their eyes to the stars instead.

That’s why when he’s producing future- or threatcasting scenarios, Johnson tries to capture some of that same “can-do” spark. Simply put, it gets things done.

“That’s one of the missions of my threatcasting lab: To empower people,” Johnson said. “Not to scare them.”

Modern sci-fi seems intent on doing just the opposite, however. Series like Black Mirror and Altered Carbon give us weighty glimpses into dystopian future hellscapes, while movies like Bladerunner 2049 and Ex Machina subtly coax us into rooting for machines, not people, to make the next evolutionary leap. The trend of dark tomorrows isn’t likely to dry up anytime soon. But what does our collective obsession with these types of stories say about us and the way we view the future?

Not as much as you might think. So says Neil Clarke, the award-winning publisher and editor-in-chief of Clarkesworld Magazine, one of the leading voices in modern science fiction. He said that, while he believes stories shouldn’t necessarily be divining rods for future outcomes, there’s still a great deal people can learn from embracing the “dark side” of science fiction.

“Sure, [sci-fi writers] may have influence, but that doesn’t have to take the form of providing answers,” he said. “Sometimes the visions seen in these stories provide incentive to avoid potential problems or inspire one to think about things they wouldn’t have normally considered.”

A science fiction writer’s only responsibility, he said, “is to tell the story, wherever that takes them.”

One writer, Mary Shelley, took that famously to heart. Penned in 1817, her horror classic Frankenstein is considered today to be one of the cornerstones of science fiction. It’s also the seminal work of the “man-made monster” subgenre, a collection of ideas which has, ironically, taken on a life of its own.

While “dark,” Johnson said Frankenstein has an underlying message of hope, if you’re willing to look for it. The same holds true for novels like William Gibson’s Neuromancer and Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, which recast Shelley’s iconic monster as a thinking machine.

“[These stories] actually have very little to do with machines,” he said, “and a lot to do with humans.”

Shelley’s nameless monster? It isn’t some confused beast. It might be, technically, but metaphorically speaking, it’s much more than that. According to Johnson, Frankenstein’s monster is a blank slate, something to which readers can attach their fears, emotions and misgivings. Robots and artificial intelligence — our modern-day monsters — work much the same way in current fiction. They serve as proxies, emotional substitutes for the traits and qualities we fear most in ourselves and in our fellow humans.

In the near term, “rogue AIs” and “robot overlords” are essentially non-threats. Especially the latter, said Johnson, joking: “I build robots. I can tell you, the majority of the time what robots do is they fall over.”

Their human counterparts are rarely so clumsy, however. A perfect example of this can be found in the health care field.

Dr. Michael Nowatkowski, associate professor of Information Security at Augusta University’s Cyber Institute, studies medical device security. In recent years, health information has become more valuable than credit card numbers on the dark web. Unfortunately, the same machines we use to gather and store that information are vulnerable to intrusion. Very much so.

Gone are the days of worry-free trips to the hospital. Even something as simple as wearing a fitness tracker could reveal sensitive health information. What makes these devices especially dangerous, though, is their interconnectivity. The fact that so much of today’s tech is joined together through the internet of things means tactics like “pivoting” can do tremendous harm.

“If the [entry point] is connected to the nurse’s workstation, hackers could pivot from the infusion pump to the nurse’s work station,” Nowatkowski said. “Any information that’s on that workstation the attacker would then have access to.”

For researchers like Nowatkowski, information security isn’t the only concern.

Former U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney avoided a potentially deadly pivot in 2007 when he requested doctors turn off the Wi-Fi functionality of his pacemaker. His fear, that hackers might deactivate the device remotely, was — and is — a very real threat.

Presently, Nowatkowski said there is little patients can do to protect themselves from a cyber intrusion in hospitals. That’s why he and other researchers are working diligently to find new and safer ways to interact with hospital equipment. With more and more smart devices hitting the market, the same dangers we face in a hospital bed could soon follow us home. It begs an important question: What are we willing to give up to be more safe?

“A lot of what the internet of things devices do is provide convenience and access,” Nowatkowski said. “People may just have to start weighing, is my security, my information more important than the convenience of not having to walk across the room to flip on a light switch?”

While things like pacemaker assassinations and FitBit superhacks are a definite possibility, Johnson cautions that the average citizen isn’t likely to fall prey to them anytime soon. Nor is New York in danger of being bombed during a mass influx of fresh produce. While it’s important for people to know these threats exist, Johnson said that building understanding is infinitely more useful than generating fear.

“When most people talk about cybersecurity or security at all, or even threats, they ultimately just try to scare people,” he said. “When you scare people and tell them that this is huge and terrible and we’re all going to die, that disempowers them, which I find at best disingenuous and at worst I find dangerous.”

When you disempower someone, Johnson said, the more likely they are to become like Bill Morgan — the dockworker from the “Two Days” scenario. Just as Morgan’s Twitter complaints opened the way for terrorists to destroy New York, the actions we take when we feel helpless can leave us open to disastrous consequences.

“The stories we tell ourselves about our future matter,” Johnson said. “The idea is to understand that when we write these stories, or when we tell these stories, we need to understand how we’re talking about them.”

For the foreseeable future, sci-fi is likely to remain dark. That doesn’t mean it has to, though. Nor does it mean we have to let it rule the way we think or the way we shape the stories about our future. In this regard, Clarke has some thoughts of his own about empowerment.

Authors, he says, are “are at their best when they write the stories they’re inspired to.” Rather than chasing trends, he encourages sci-fi storytellers to take charge of their futures.

“The reason you might not be seeing many of those bright vision stories could simply be a market shortage,” he said. “A new trend doesn’t happen without stories to shape it.”

And that, Johnson would surely agree, is no fiction.

The Future Starts With You: Asking questions today for a brighter tomorrow

You may have heard of Jeff Bezos. He’s currently the richest man alive, with a higher net worth than the GDPs of Panama, Uruguay and Haiti combined. What you may not know is how he got his start — on his knees, packing boxes on a concrete floor. In a now legendary soundbite, the Amazon founder and CEO (whose net worth soared past the $120 billion mark earlier this year) shared the story of the innovation that put him back on his feet.

“We were packing on our hands and knees on a hard concrete floor, and I had this brainstorm,” Bezos said. “I said to the person next to me…‘You know what we need?’…‘We need kneepads.’”

Rather than accepting the CEO’s suggestion, as some might have done, Bezos said his employee pushed back. What they needed, the employee said, were packing tables.

Modeled after the original tables Bezos and his employees threw together from solid core doors and four-by-fours, the “door desk” is now a staple of Amazon office decor. More central to the company’s success, though, is the question that inspired its design: What can we do to make our own futures better?

Brian David Johnson, leading futurist and director of the Threatcasting Lab at Arizona State University, said few questions are more important when it comes to thinking about tomorrow.

“What are we trying to get done?” Johnson said. “Everyone needs to ask that question. Whether it be for a business or what you might be doing with technology, what are you trying to do?”

Johnson frequently works with experts from a number of different fields to host futurecasting sessions — roundtable discussions that focus on envisioning, and working toward, better futures. Often, though, his conversations about the future happen one-on-one. Speaking with everyone from human resources professionals to hiring managers and IT attorneys, he asks questions about the processes and procedures that make organizations tick. His hope for any such conversation, he said, is to create a culture that rewards curiosity and creative problem-solving.

“One of the things we do as a part of that is to create a culture that is always looking, always thinking … always keeping an eye out for things that are new, things that are interesting,” he said.

To illustrate his point, he used the example of a potential disruptor — in this case, an earthquake off the coast of Alaska.

“You don’t respond to it a month before it happens; that’s impossible,” he said. “You don’t respond to it a month after it happened; that’s irresponsible.”

Instead, he said, the key is to investigate the new thing when it happens, to understand it and to ask yourself, how does this affect the plan or the model I — or we — have set for the future? From there, Johnson said, making the future better is as simple as building a new model, one that addresses the issue and puts a plan in place to deal with similar issues later on.

It isn’t an easy thing to do. So often we find ourselves in the shoes of Bezos’ other employees, sitting on our knees hoping for packing tables but accepting kneepads because our boss tells us it’s what’s best for us. Johnson’s message is a simple one, though. Only you can change your own future. And you should want to. Every day.

“Humans build the future,” he said. “The future involves everybody, and it worries me when it doesn’t happen.”

Until recently, though, that line of thinking wasn’t the norm.

When Johnson, a Gen Xer, was first coming into his own as a futurist, he said the generations ahead of him — the baby boomers and the Silent Generation — had a very different view of how the world worked. They found it “laughable and contemptible” to be a futurist. It was considered a show of arrogance to look critically at the future, to question the status quo or go against the way things had previously been done.

Thankfully, younger generations are moving in a more future-focused direction.

“What’s interesting to me, as we’ve moved through the generations and into the 21st century, you see this next generation of millennials and Gen Z who feel empowered,” Johnson said. “[They] have seen whole businesses can be built and made and succeed or fail in the span of 5 to 10 years. That time scale, and oftentimes that optimism, to me, is great.”

But what about the older generations? The Gen Xers, the baby boomers or even some of the later millennials? To change their futures, should they live more like youngsters-at-heart? Or drift through their days thinking only of the future? Hardly. Change and the steps needed to achieve it, as Bezos and his employees learned nearly two decades ago, don’t have to be drastic or world-ending to make the future better. They just have to be driven by curiosity.

An Amazon employee once changed his future, and the future of his entire company, by asking a simple question: What will get me off of my knees?

To build a better, brighter future of our own, we must never be afraid to do the same.