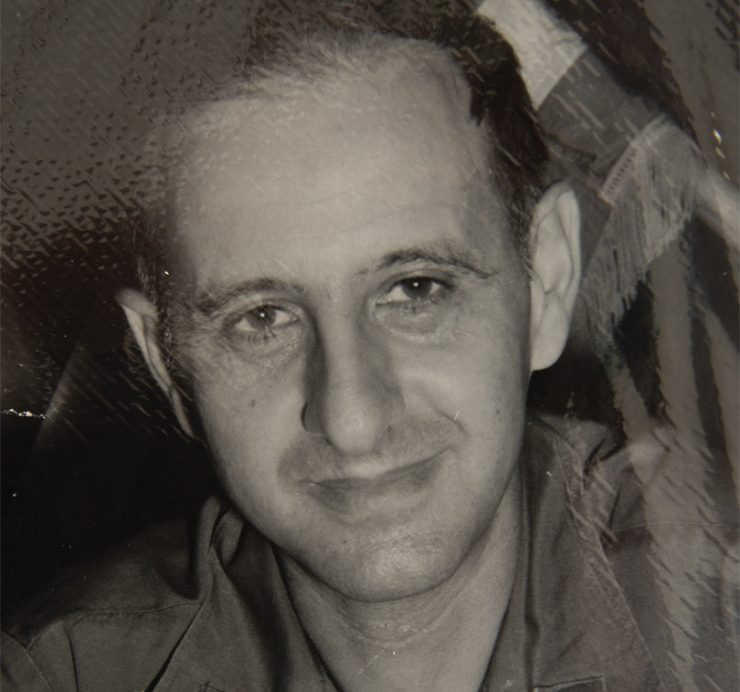

Dr. Edmund Krekorian fought in three wars—then wrote about it.

He was 17 years old. Pearl Harbor was still a piercing memory, and like most young men of his age, his patriotic fervor burned.

After enlisting in the U.S. Marine Corps in May 1943, Edmund Krekorian, ‘57, headed to the Pacific, serving in the Northern Solomons, Bismarck Archipelago, the St. Mathias Islands and the Admiralties. He remembers vividly the cruel treatment of prisoners of war by the Japanese, the loss of fellow Marines and finally the use of atomic weapons that made the invasion of Japan unnecessary and ended World War II.

“And as a teenage Marine private first class reading about prominent Army and Marine generals from both European and Pacific Theaters, I never dreamed one day they would become my patients,” said Krekorian, who would go on to become a prominent otolaryngologist.

But he not only lived it. He wrote about it. After a career in the military and in medicine, Krekorian has written three novels, much of which are based on his experiences in World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War.

This is his story.

Military Meets Medicine

“I was never much of a scholar,” said Krekorian. After discharge from the Marine Corps and three years at Emory University, he eagerly accepted a direct commission as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army. Soon after, he met the sister of his best friend, a fellow lieutenant. It was love at first sight. On June 30, 1950, he married Patricia Ann James of Royston, Georgia, a graduate art student at the University of Georgia. That was the same day President Harry Truman committed U.S. ground forces to the defense of South Korea.

Five weeks later, Second Lieutenant Krekorian was the commander of an automatic weapons platoon defending Yonil Airfield at P’ohang-dong, the eastern anchor of the Pusan Perimeter. His platoon, under orders of “no retreat,” endured days of intense shelling and fought off multiple probes. Then on September 6 came the marine invasion of Inchon, where United Nations forces pushed the North Koreans back into North Korea and across the Yalu River into Manchuria. Krekorian’s platoon advanced to a small airfield 40 miles south of the river with orders to keep the field open for the air evacuations of casualties.

By December 1950, a major intervention by the Communist Chinese People’s Army forced UN armies back into South Korea. A month later, Krekorian transferred to the Third Infantry Division to command a platoon that included self-propelled automatic weapons. By mid-April, his division had reached the 38th Parallel, and on April 22, the Chinese communists launched a massive offensive, mobilizing three field armies 700,000 men strong, focused on driving UN forces off the Korean peninsula.

Next came the moment that would put him on the path to medicine.

“Our platoon was tasked with evacuating 16 severely wounded British from under the noses of the Chinese, before the Chinese could take them prisoner,” he remembered. “We evacuated them to a MASH hospital and I stood by the emergency room door as the stretchers with the wounded were being brought off the tanks. As each stretcher passed, the British wounded would grab my arm or squeeze my hand and say, “God bless you, yank,’ or ‘God bless America.’

“After two wars, I thought I was pretty tough. But that brought tears to my eyes.”

The MASH doctors, knowing that Krekorian was responsible for the rescue, invited him to observe the treatments. As he watched, “It convinced me that I had to be a doctor.”

But there was still a long way to go.

Krekorian was soon able to rotate back to the United States, just in time for his first wedding anniversary. He served as an intelligence officer for a time in New York City before returning home with Patricia and finishing his fourth year at Emory. But “great grades” that last year didn’t make up for his poor GPA from his first three years: “I was getting a record number of medical school rejections, and most didn’t even ask for an interview,” he said.

But Patricia’s cousin Hubert Anthony Jr. happened to be a sophomore at the Medical College of Georgia. He took the bold step of going directly to the office of Janet Newton, then director of admissions — a “formidable lady.” “Hubert Jr. told her that the Medical College of Georgia was making a mistake if they didn’t at least interview me.”

Newton apparently admired Anthony’s guts. Krekorian got a “nice letter” inviting him for an interview, but the interview itself? “The only thing missing was waterboarding,” recalled Krekorian with a wry chuckle. Dr. Corbitt Thigpen, chair of psychiatry; Dr. Phillip Dow, a professor in the Department of Physiology; and Newton grilled Krekorian on everything from his poor grades to possible “hang-ups” from two wars.

But Krekorian was also able to speak eloquently about that spiritual moment in a MASH hospital half a world away and this fact: “I knew exactly what I wanted to be — I wanted to be a doctor, one way or another.”

A postcard arrived soon after, with his acceptance. “And that’s the story of how I got into MCG. I’m grateful to MCG for accepting me. It turned my life around,” said Krekorian, who has given back nearly every year to his alma mater for more than 50 years. He was also recognized in 2014 as the MCG Distinguished Alumnus for Professional Achievement.

An Honor and a Privilege

How Krekorian got into medical school could be described as a lucky break. Ditto for how he became a highly recognized otolaryngologist/head and neck surgeon. “By the time I applied, most army residencies had been filled, but there was still one vacancy in otolaryngology/head and neck surgery,” he said. “I was accepted for that residency at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio. I think it was the wisest decision the army and I ever made.”

Head and neck surgery had recently become part of the specialty along with facial plastic surgery and reconstructive surgery. Krekorian was learning all the time, diving into postgraduate courses in head and neck surgery at Columbia Presbyterian, the University of Illinois, the University of California at Los Angeles, Mount Sinai and others. In 1964, Krekorian, a major by this time, was assigned as assistant chief, Department of Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C. Eighteen months later, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel and made chief of the department.

As chief, he had the privilege of providing care for Supreme Court justices; former presidents, including those from foreign countries; cabinet members; and senators, representatives and their families. He was also appointed consultant to the Army Surgeon General and became a member of the National Academy of Sciences.

Krekorian also developed innovative approaches to skull base surgery for previously fatal conditions of the head and neck — both benign and malignant — as well as conditions due to war trauma of the head and neck.

One patient, a 17-year-old boy with intractable bleeding, was diagnosed with juvenile angiofibroma with intracranial extension. Until that time, most patients with the condition eventually died of blood loss, infection or both. Krekorian and his team, including a neurosurgeon, performed a combined approach in which both the intracranial and extracranial tumor were removed in the same operation. That young man would go on to graduate from college, marry and have three children. And when Krekorian published the case in Laryngoscope, more than 200 requests for reprints poured in from all over the world, including China and the former Soviet Union.

Then came Vietnam. Soldiers with severe trauma of the head and neck poured into Walter Reed.

With 20 years in active duty, Krekorian was eligible to retire from service — and offers were coming in from Johns Hopkins and Washington University for chair positions in his specialty. The prestige — and the money — were enticing, but Krekorian could think only of the young soldiers “with severe crippling and disfiguring wounds.” So for the third time in his life, he went to war.

During the conflict, he served as the division surgeon for the Americal Division, also known as the 23rd Infantry Division — 25,000 men strong — as well as the head and neck surgery consultant, southeast Asia, for the U.S. Army. He operated on wounded U.S. soldiers, the South Vietnamese, North Vietnamese soldiers, the Viet Cong, and civilian men, women and children. He also flew to other U.S. hospitals in Vietnam to assist with complex head and neck injuries, and later was promoted to full colonel, assigned to command a 400-bed U.S. Army Evacuation Hospital just outside of Saigon.

A New Career

The memories of that time in combat linger, even after returning from war and moving his family to Denver, Colorado, for a position at Fitzsimmons Army Hospital. In 1978, he retired from the army and joined the faculty of the University of Colorado School of Medicine and the staffs of the University of Colorado Hospital, Denver General, the Denver VA and Denver Children’s Hospital. He retired as a professor emeritus in 1991. “I loved practicing medicine up until the day I retired,” he said.

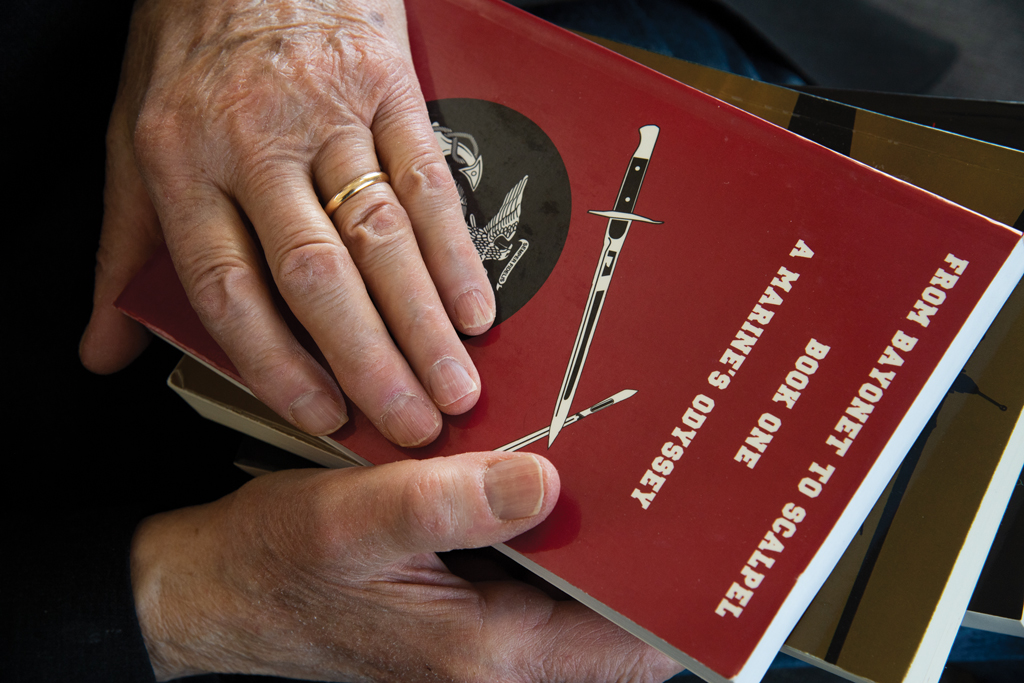

Then what most retired doctors fear will happen did happen: He was bored. So he started to write down his memories. Krekorian had authored short articles before on his war experiences. A novel — even one based roughly 80 percent on his own experiences — was a different proposition altogether. But the words flowed. From Bayonet to Scalpel: A Marine’s Odyssey was published in 1996, followed by Vietnam: A Surgeon’s Odyssey in 2003. Then, pure fiction: Operation Geriatric Geese in 2016.

He’s still continuing to write, but his life now is filled with family: wife and artist, Patricia, whom he still calls “quite a girl”; three sons and one daughter; four grandchildren; and two great-grandchildren. The memories may still be strong, but combat, these days, seems far, far away.

Read About It

Dr. Edmund Krekorian’s three novels based on his own experiences as a serviceman and physician in three wars are available on Amazon.com. Copies are also available in the Greenblatt Library on the Health Sciences Campus of Augusta University.