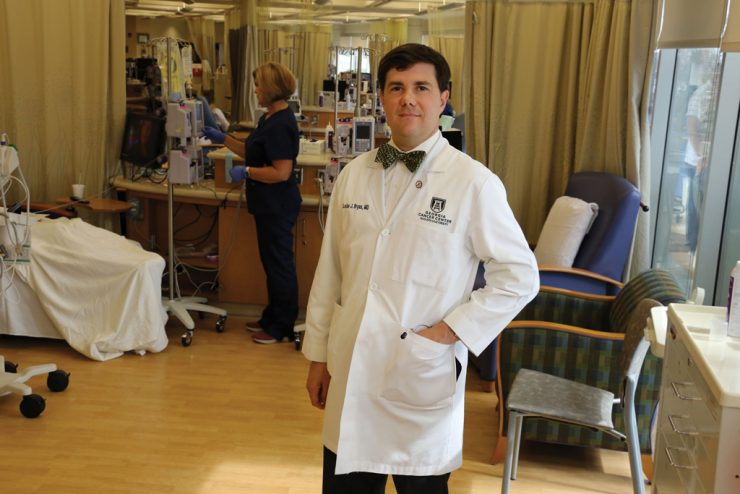

When Dr. Locke J. Bryan, an assistant professor in the Department of Medicine at the Medical College of Georgia and a physician with the Georgia Cancer Center, explains immunotherapy to his patients, he usually brings up something they’re likely to understand — the concept of the immune system fighting infections.

The thing about the immune system, he tells them, is that it can also be very good at fighting cancer.

To some extent, cancers know that and can actually turn off the immune system, preventing it from putting up a fight against the multiplying army of invaders. But when the immune system can be marshaled to join the fight, he says, it can be a powerful force.

The idea of enlisting the body’s immune system to battle cancer began back in the 1970s with the use of allogeneic stem cell transplants, which basically replace a patient’s immune system with that of a donor. Later, the use of monoclonal antibodies came, which are proteins that bind to cancer cells, attempting to turn on the cancer cell’s suicide system or shut down the cancer cell’s metabolism. Even more recently, little pieces of chemotherapy or radiation have been attached to the proteins so that when they bind to the cancer cell they can deliver the treatment at a cellular level.

Bryan is researching how adding an immunotherapy drug to an existing regimen of chemotherapy can affect treatment outcomes in Hodgkin lymphoma patients who have relapsed or failed to respond to initial treatment.

Typically, Hodgkin lymphoma is a responsive disease with very good outcomes. The small minority of patients who relapse or don’t respond well to the treatment undergo a relatively standard course of therapy: a short course of chemotherapy (typically a combination chemotherapy known as ICE) to get into remission, followed by an autologous stem cell transplant, which is a transplant using the patient’s own cells. To achieve this, physicians harvest the stem cells, give a megadose of chemotherapy which takes out the bone marrow and immune system, then restart the system by returning the harvested cells. If patients fail treatment following an autologous stem cell transplant, the standard therapy later includes a class of immunotherapy called checkpoint inhibitors, which includes the drug pembrolizumab.

Currently, Bryan is investigating whether adding pembrolizumab to ICE combination chemotherapy improves treatment outcomes.

“What we’re expecting to show is that people get into a better remission and that will translate into a better benefit from the transplant and a better chance of the disease never coming back,” Bryan says.

If this early-phase clinical trial proves effective, the use of checkpoint inhibitors could be moved up in the treatment order.

“It moves a drug that people wouldn’t normally see for a while to the front so that hopefully we can eliminate people from having disease relapse and needing more therapy down the road,” Bryan says.

According to Bryan, it’s the kind of research Augusta University is known for, giving Georgia Cancer Center patients the absolute latest in treatment options.

“I think the novel thing we have here is that the institution has been looking at immunotherapy and the role of the immune system in cancer for a long time,” he says. “It’s certainly the hot trend and really the direction that treatment is headed across the country and across the world.”