Obesity is not an identity, it’s a disease, say the doctors who treat it.

Actually it is more like an epidemic, affecting better than one third of American adults living in all states and 1 in 5 children, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Its comorbidities include other top diseases like heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea and more than a dozen different types of cancers. The South and Midwest have the highest prevalence at better than 32 percent of the population in each, the CDC says.

While much remains unknown, there are known causes of obesity, including genetics, environment and lifestyle, a shifting society that has transformed food into entertainment rather than fuel, made high-fat, high-calorie food available by rolling down a car window and physical activity something many of us have to schedule.

How best to fight particularly significant obesity also is a complex, ongoing discussion in which bariatric surgery is becoming a more common talking point and practice. The sleeve gastrectomy, in which a patient’s stomach is significantly trimmed to about banana-size for example, has gone up nearly 60 percent in the last half dozen years.

Bariatric surgery chief Dr. L. Renee Hilton, ’11, grew up in Edison, Georgia, population now about 1,500, on the family farm started by grandparents Ralph and Betty Lou Hilton. Her parents, Lamar and Lisa Hilton still live across the peanut field from Betty Lou and there are still aunts, her sister and cousins aplenty. Her grandfather, now deceased, was among those who helped show Hilton she could do anything by letting her, from driving tractors to chopping firewood, even as a kid. He also assured her she could do it better than most if she put her mind to it. It was a strong supportive group of men and women Hilton was privileged to grow up among in Edison. About 30 of them would show up with megaphones in the stands just to watch her play high school basketball. No doubt, she says, that makes a tremendous difference in realizing your potential.

Hilton started telling them when she was still in the single digit ages that what she wanted was to be a doctor. By high school, the first time she stepped into an operating room – courtesy of mom’s connections – in Cuthbert, Georgia, she knew she wanted to be a surgeon. The way the patient trusted the surgeon to cut him open so he could heal: “It kind of rocked my entire world,” says Hilton.

The University of Georgia graduate liked MCG’s mission of giving back to the state she also loved. So she applied for early decision and when she was accepted, she was the top headline at the local grocery store, where the week’s sale items would normally be.

She met husband Jacky Rowe on a blind date while a fourth-year student at MCG. They ended up dancing half the night to Frank Sinatra and got married the third year of her residency, although he technically proposed after their second date. He now runs the 152-acre farm they own in Richmond County.

She did her surgery residency at Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami, the teaching hospital of the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, including a year as chief resident. During residency she was captivated again, this time by big surgeries performed through four tiny incisions. She just had to do that. There was another professional epiphany when she saw a bariatric case, a patient with high blood pressure, diabetes and sleep apnea who immediately came off all their medications and CPAP within a few months. “I was just so impressed with the medical comorbidities that we were able to treat with surgery.”

Hilton would next pursue a rare, combined minimally invasive and bariatric surgery fellowship at Yale University.

Then she, like MCG, felt a calling to serve her home state. Hilton returned to her alma mater in 2017, where she is now chief of the Section of Minimally Invasive and Bariatric Surgery in the Department of Surgery, director of Bariatric Surgery and the Center for Obesity and Metabolism and co-director of the Digestive Health Center at AU Health.

The last weekend in April Hilton’s large, Edison, Georgia-based fan club showed up again, this time as she received the MCG Alumni Association’s 2019 Outstanding Young Alumnus Award.

A bad rap

Like people battling obesity, bariatric surgery can have a bad rap, mostly from the early days a half century ago when big open and generally more extensive surgeries led to problems with mal-nourishment, surgical complications and even death. “Patients were losing weight but they were also losing their hair and vitamins and minerals,” Hilton says.

“Someone once asked me, ‘Wouldn’t you rather cut out cancer or operate on heart disease?’ I told them I would rather just prevent patients from ever needing those operations,” she says, noting the friendly fire that has come at her as well.

Yes, we all eat food we shouldn’t and many of us don’t exercise as we should, but obesity is just way more complicated, Hilton says. “There is a genetic component. There is a hormonal component and a lot of other mechanisms and pathways within the body that we don’t understand yet.”

There are those people who can have unhealthy behavior that does not show up on the scale and those whose diligent efforts to be trim and healthy don’t show up on the scale either.

Conversations with her patients rarely start with how they want to get back into their favorite jeans, rather with how they want to get back to their lives.

“A lot of these patients feel miserable. They can’t play with their grandkids or they can’t play with their own kids. They can’t tie their own shoes. They can’t walk into work every day without having to stop and rest on a bench because they get short of breath. Or they are worried they are going to have a heart attack like their parents or they are going to get cancer,” she says. They may need an organ transplant or want to have a baby and obesity can prohibit both.

“It’s hard for a lot of our patients to even seek surgery because they feel really guilty about their weight when truly most should have no guilt,” says her partner and fellow classmate Dr. Aaron Bolduc. “You don’t feel guilty going and seeing a cancer doctor or getting your blood pressure treated.”

It goes back to obesity being a condition not an identity, he says.

“No one gets to bariatric surgery without having made lifestyle changes that failed,” adds Hilton. “No one is excited the first time they meet me. They all walk in feeling like they have already failed at something. I try to make them understand they have not failed.”

Patients may cry and Hilton may cry with them. Then she tells them more about a metabolic tool that might get their bodies working with them again.

BMI is just a beginning

Most of their patients are 100 pounds overweight and female. But meeting the body mass index – a ratio of height to weight – for obesity is only a starting point for bariatric surgery. The team sees their patients three to six months before surgery, to provide instruction in diet, exercise and to overall prepare and evaluate them. They cover everything from resolving smoking and other addiction problems – use is a nonstarter – to discussions about the need for every female of reproductive age to be on birth control because pregnancy and delivery are many times safer for mother and baby after bariatric surgery.

“There are a lot of positive implications,” says Bolduc, when obesity is removed as a barrier.

Dr. Christian Lemmon, a psychologist specializing in eating disorders and obesity, helps sort through issues like whether their depression, which is common in patients, results from struggles with obesity or from the neurochemistry in their brains. Some patients have PTSD, some survivors of child abuse who put on weight as protection. That’s why Lemmon sees the patients before and after surgery as needed.

He also must help them understand that nothing ends when they go home, to decide whether they want to tell friends that they have had the surgery and, if not, how to answer questions about why they are now only eating a fraction of a chicken breast at dinner and/or how they lost so much weight.

Patients, many of whom cannot walk down a street without being harassed, have to be committed to lifestyle changes, maybe even friend changes and learn to better deal with stress. He does a lot of “have you considered.” Like the Alcoholics Anonymous model, the success improves when patients have strong social support outside their medical team, Lemmon says.

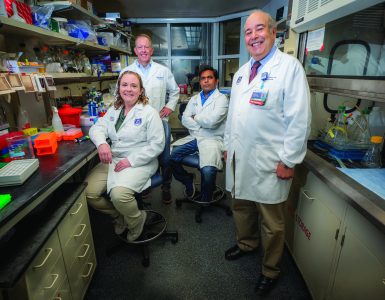

The team – Surgeons Hilton and Bolduc; Psychologist Lemmon; Nurse Coordinator Maria Immonen; Advanced Practice Nurse Kristen Benjamin; Dietitians Andrew Yurechko and Dena McGhee; and Registered Nurse Liz Hurt – will make a group decision on whether bariatric surgery is the right choice for a patient. Last year, the team added adolescent surgery to their qualifications and adolescent medicine specialist Dr. Robert Pendergrast to their team.

With research and experience, the MCG team has found that the best procedures are the sleeve gastrectomy, in which about 80 percent of the stomach is removed to create that banana-sized stomach, and gastric bypass. Gastric bypass is still considered the gold standard of bariatric surgery, a technique in which a smaller stomach pouch and shorter small intestine is created, so patients feel full with less and likely absorb fewer calories and nutrients. Perhaps most importantly, both surgeries immediately alter the function of gut hormones like the hunger hormone ghrelin and blood glucose control. The once common gastric band has fallen out of favor with academic centers, Hilton notes, because of frequent complications, including the need for more surgery and removal of the band that is restricting a major portion of the stomach. At MCG and AU Health, Hilton and Bolduc perform slightly more sleeves than gastric bypasses, in keeping with current national trends.

The team sees patients two weeks postop, then at six months, then one year and annually for five years. The American Society for Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery requires two years of follow up, but the MCG team follows patients for years to help ensure basics like vitamin and mineral levels remain good, that their weight loss is healthy, and so patients can get any questions answered as they move on with their lives. They will follow them indefinitely if a patient wants, and will continue to work with a patient’s primary care doctor.

The recent addition of adolescents makes the already complex evaluation process perhaps more complex because the decision to operate now has to be a consensus of the team, the parents and the child. It’s often the parents “pumping the brakes” about the surgery and the children, already weary of being sick and the butt of jokes, pushing for it. The team definitely finds itself voting no, or at least not yet, more often for children.

Young patients are facing a lifetime of lifestyle changes and when complications do happen, a lifetime of living with consequences, says Hilton.

Still the bottom line is really the same for good adolescent and adult candidates alike: the benefits likely far outweigh any risks.

“We have a high percentage of our pediatric population with obesity in the Southeast, particularly in Georgia,” Hilton says, where about 20 percent of adolescents have obesity.

“These are not children who are a little overweight. These are children who are 13 years old and already have diabetes, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea … and are going to end up developing macrovascular disease by the time they are in their 30s.”

Instant, lasting results

Hilton and Bolduc still are amazed by some of the instantaneous results in patients – how they have surgery on a Tuesday and go home on Wednesday, off both their blood pressure medications and 70 units of daily insulin before weight loss has even kicked in.

That reaffirms the fact that it is metabolic surgery, they say.

“Our bodies are designed to avoid starvation, that is why it’s so easy to put on weight,” says Bolduc. “When we are starving, we will avoid things like healing wounds and growing just to preserve our weight. So we have a lot of mechanisms to overcome with surgery.”

Ghrelin, he says, is one of the clearest examples. It’s a gut hormone that causes our stomach to growl, signals our brains to eat, enables fat deposition and release of growth factors. It’s levels are generally regulated by how much we eat and levels actually have been shown to increase with a restrictive diet. The sleeve, for example, which dramatically reduces the size of ghrelin’s production plant in the stomach, takes levels way down immediately. Like many things in bariatric surgery, the research followed the clinical work and it has been found that about 90 percent of our ghrelin comes from the cells in the top part of the stomach, which is removed in the sleeve gastrectomy, Bolduc says.

Take the stress hormone cortisol, a steroid hormone with a myriad of jobs including helping regulate blood glucose levels and metabolism and blood pressure. There is emerging evidence that chronic stress, including lack of sleep and consumption of high glycemic index – essentially carbohydrates – foods like white bread, white rice and saltines, can produce more cortisol, which can help shift fat to our bellies, make us crave more of these foods, even decrease our muscle mass. Individuals with obesity generally have higher cortisol levels, in fact one study correlated children with the highest levels of cortisol concentration in their hair – where it’s often measured to get a longer perspective on its levels – as having a nearly tenfold risk of obesity. Weight loss from bariatric surgery has been consistently shown to reduce circulating cortisol levels.

Take inflammation. Obesity is a major contributor to inflammation – a factor in every major disease from cancer to heart disease – and it’s one of the first things that decreases, likely at least in part because a smaller stomach means less exposure to bile, which is essential to digestion but helps you absorb fat and regulates inflammation. In fact, research done at Vanderbilt showed that like his patients, mice in which bile made a quicker trip from the liver to the intestines, were thinner, Bolduc says.

Take the irony of a super-efficient metabolic rate. Not unlike cancers that turn so many of our body systems against us, ironically losing weight through the myriad of intensive diet and exercise regimens can tune down our resting metabolic rate – basically how many calories we burn to perform basics like breathing – likely leaving us still more vulnerable to weight gain.

Conversely, studies have shown that bariatric surgery can rev up resting metabolic rates and turn down metabolic syndrome, a cluster of unhealthy parameters like high glucose and bad cholesterol levels in the blood.

“That is where people really benefit from bariatric surgery. The analogy is bariatric surgery is almost like resetting your internal thermostat,” Hilton says.

But she reiterates, here and to patients, that surgery is a tool, albeit probably the best one she can give to help get their bodies working for them again.

“I will tell anyone who will listen that my patients are the bravest, most courageous, amazing people,” says Hilton, a member of the Executive Board of the Georgia Chapter of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery and of ASMBS’ national Access to Care Committee.

This past legislative session, the folks she talked with included the Georgia Legislature and Governor’s office, because she is working to get the procedures covered by the state’s insurance plans. At the moment, Georgia is one of seven states in the nation that don’t provide that coverage to state employees. Paying out of pocket is a nonstarter for many, but the fiscal reality, she says, is that the sleeve procedure, for example, which has a mortality rate of about .01 percent, costs about $18,000 while a year’s treatment for diabetes costs $17,000. She hopes the math and her patients will soon enable Georgia to make that change.

“Within two years you have recouped the investment just on the cost of diabetes,” notes Bolduc, never mind the complications of diabetes, the cost of blood pressure medicine, hospitalizations related to either. The big plus is you don’t have any of that anymore, Bolduc says, and the patient feels and lives better.

With one in three among us having obesity, “I think prevention is our best bet for public health but we don’t have a good solution right now,” he says. “But for treatment once patients have obesity, surgery is a really good option.”

Getting back to life

Both surgeons, clearly happy with what they do and, better yet, with how their patients do, still are out there pushing the envelope for still better care and results. Bolduc suspects better medical therapies and at least one more surgery are in their not so distant future.

Their own studies, in collaboration with Dr. Neal Weintraub, cardiologist, associate director of the MCG Vascular Biology Center and Georgia Research Alliance Herbert S. Kupperman Eminent Scholar in Cardiovascular Medicine, include perusing the fat of lean and obese humans to identify differences and maybe new treatment targets.

One of the many things obesity can prevent is an organ transplant, so they also are working with the transplant team at MCG and AU Health to shorten the time to transplant for patients. They are working with cardiologist Dr. Pascha Schafer to better restore cardiac function in patients who are in heart failure because their body size has outgrown their heart’s capacity.

Four MCG students in the Medical Scholar’s Program will be spending the summer with the bariatric team researching related issues like optimal long-term follow up for patients and how patients are benefiting from a social media support group the center has already started. They already know patients are using the site to swap recipes – Hilton has been known to share a smoothie recipe – and common experiences but want to know if this kind of virtual support makes an impact on lasting outcomes. They have an actual support group that gathers monthly.

“The idea would be to target future treatments for obesity … the end game is always finding better treatment options for obesity,” Hilton says.

Footnotes

Hilton and Bolduc are classmates, but he also completed his surgery residency at MCG, including a year as chief resident and another year to do research, before going off to do his combined bariatric and foregut surgery fellowship at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. While he was chief resident, he saw Hilton’s curriculum vitae come across his desk as the Department of Surgery was looking to rebuild a bariatric program, and thought she was a great choice. He joined her last year after completing his fellowship.

The American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, or ASMBS, the largest society for the specialty of bariatric surgery and the accrediting body for Centers of Excellence, has awarded AU Health its highest designation as a Comprehensive Center with Adolescent Qualifications.

Weighing in

As far back as 1998, the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute stated that advances in bariatric surgery meant its clinical guidelines could now support the surgery in well-informed, motivated individuals with a body mass index – a ratio of height to weight – of 40 or greater whose quality of life was severely impacted. Also, for patients with a BMI of 35 or more with obesity-related comorbidities who were well enough for the surgery. The NHLBI’s guidelines further recommended a lifelong maintenance program that included diet, exercise and behavioral support and frequent contact between patient and practitioner over the long-term.

In 2011, the American Heart Association said it recommends bariatric surgery for patients with severe obesity who have failed medical therapy but called for long-term data, which surgeons like Hilton and Bolduc want as well. Groups like the American Heart Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American Diabetes Association have said in more recent years that bariatric surgery can mitigate some of the serious comorbidities of obesity.

A 2013 study in The BMJ (The British Medical Journal) that looked at 11 trials following nearly 800 obese individuals with a BMI between 30 and 52 who had bariatric surgery or nonsurgical intervention, like a weight-loss drug, found those who had bariatric surgery lost more weight and had higher remission rates of diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Blood profile was also most improved in the surgery group, but blood pressure changes were similar in both groups. There also were no surgery-related deaths, although some patients developed iron deficiency and needed more surgery.

Hitting the Reset Button

Growing up in Clinton, Indiana, he remembers the bright yellow tag on the back of his pants that said “Husky.”

“It was like a big, flashing caution sign,” says Dr. Beau P. Gedrick, with a characteristic grin. “Everybody knew you were wearing huskies so they made fun of you.”

Gedrick, a primary care sports medicine physician at MCG, quickly learned to beat others to it by making a joke at his own expense. “You get good at it,” he says. “You get a laugh out of them and then you move on.” But you don’t really.

Even after he put aside the husky pants, played high school defensive end, weight lifted and sprinted, and played college football. Even after getting into medical school, marrying wife Brooke and even after they had two children whose names also start with “B’s” Bryce, 7 and Briley, 5, a day would hardly pass when his weight was not on his mind.

“I have lost a major amount of weight four or five different times,” Gedrick says. “It would stay off a couple of years, then slowly it would creep back up.” He tried it all: no carbs, low carbs, fasting, Weight Watchers, SlimFast, just eating well-balanced meals and increasing physical activity. “All the way from sweating it off, to spitting it out.”

After college, he went to work nights at Pfizer, ate out of vending machines, didn’t exercise, stressed about medical school and gained 20-30 pounds. He gained about the same amount in his first two years of medical school at Nova Southeastern University College of Osteopathic Medicine in Fort Lauderdale, and the same again when medical school shifted toward those last two clinical focused years. He piled on more during his emergency medicine residency, when the children were born, even during his primary care sports medicine fellowship.

He knew the bias, even had an attending during his fellowship regularly challenge him to physical competitions like pushups and sit ups. Gedrick kept up with him, likely even earned some of his respect, but the teasing still hurt and probably angered him. “People a lot of times make assumptions. You are dumb, you stink, you can’t do certain things. I shocked a lot of classmates when we would go play flag football.”

He felt he had to apologize to everyone for his weight, to himself, his kids, his patients.

Gedrick freely admits that he has always liked to eat when he is sad, happy, celebrating or just bored. “I never sat down and ate a whole carton of ice cream or an entire bag of chips,” he says. But if you put bread and chocolate in front of him, he is going for the bread, and laughs at the suggestion of putting the chocolate on the bread.

So he blamed himself, but perhaps it is the physician in him that also recognized genetics was a factor, and who would later learn there were hormonal factors as well.

He had watched his father Chuck’s weight creep up over time. His mother Kathy was one of the last victims of polio before the vaccine, which limited her physical activity, and she ultimately needed the full, older gastric bypass procedure.

His career brought him to MCG in 2016, primarily to work in the Department of Emergency Medicine, but just last year he switched his primary appointment to the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and is now medical director of the walk-in clinic Ortho On-Demand.

Like many of his life changes, he liked the moves but they were still a stressor. There was also the reality that he and his wife, an emergency medicine physician, were now both working. They could go and do more, afford some places they couldn’t before. Have the dessert or an extra glass of wine. He gained more weight.

“One day I would wake up and I would put on a shirt I used to be able to wear and it didn’t fit anymore,” he says.

He found his go-to list for weight loss also no longer fit, even short term. He knew that bariatric surgery about a half dozen years earlier had helped his mother. Most recently, his father almost died from taking anti-inflammatory drugs that dug a hole in his intestines. Surgeons had to do what amounted to a partial gastric bypass on him as well by taking out a length of intestine just below his stomach.

Dad also dropped a lot weight, and Gedrick started thinking about surgery.

He talked with other doctors, did his own research, learned more like how stress hormones like cortisol are a double-edged sword that can help us run from a tiger but, in a chronic worrier like him, might also result in an unhealthy shift in fat and make him crave unhealthy foods even more. He was still not excusing himself, only acknowledging that his wiring is set up for weight problems and that he likely helped further break his wiring over time.

At near six feet tall, he weighed 327 pounds at age 37. His blood pressure was becoming a problem. He had sleep apnea. He was worried about diabetes. He couldn’t bend over to tie his shoes. He couldn’t play on the floor with his kids like he wanted. His knees were hurting.

Still in the emergency room, he had seen some of the complications of bariatric surgery. It was not an easy decision but, even at his young age, he felt surgery was frankly his last option. It was the time he already had lost with his family and with experiencing life that ultimately made his decision.

“I needed to hit a reset button. I know it’s only a tool and I can blow it out of the water if I want to.”

Hilton performed the gastric sleeve on Valentine’s Day 2019.

The naturally good soul cannot pretend he was happy to have surgery. “You take it personally. I let myself get like this and stay like this and now I have had to ask for help.” But he was forthright about the surgery, making sure in particular that his overweight friends knew what he had done, so they wouldn’t think, like he had so many times, that he was succeeding while they were not.

Fast forward to April 1. He is happy. Gedrick had dropped about 50 pounds. His clothes fit. He thinks maybe his ghrelin, that aggravating hunger pangs hormone, is quieter. His food preferences seem to have shifted. He had already joined a CrossFit gym before surgery and is making time for it in his life.

“I feel great,” he says. “My hope is I can be healthy and feel good and keep it that way.”