Aging Fat and Alzheimer’s Connection

Aging Fat and Alzheimer’s Connection

Scientists want to know whether our aging fat cells are important to the onset and progression of Alzheimer’s.

They have evidence that as we age, our fat becomes less efficient at producing a hormone that helps support the growth and survival of neurons and helps regulate their activity. The result can be neurons in areas of the brain important to learning and memory become dysfunctional, degenerate and we develop Alzheimer’s.

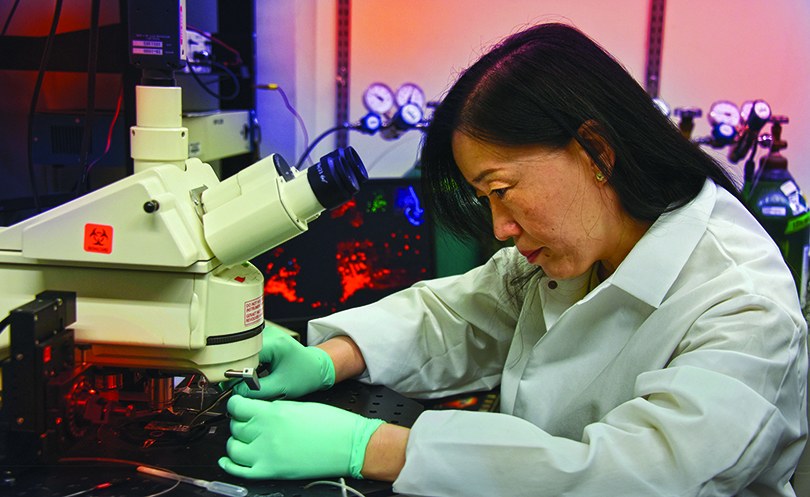

“What happens to neurons, that is really what we are interested in,” says

Dr. Xin-Yun Lu, molecular behavioral neuroscientist and Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar in Trans-lational Neuroscience.

Lu is principal investigator on a $3.5 million grant from the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health that is helping further explore the possibility that improving the function of our older fat may just help our brains.

The hormone is adiponectin, which is made by fat cells, circulates in our blood and enters our brain. Inside fat cells, its production is regulated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, or PPAR-γ, a transcription factor that’s essential for early stage fat cells to become mature, fully functioning ones.

“We know when you have Alz-heimer’s your adiponectin is low, now we want to make sure this is actually a cause,” Lu says.

Why Clear Margins Are Such Good News

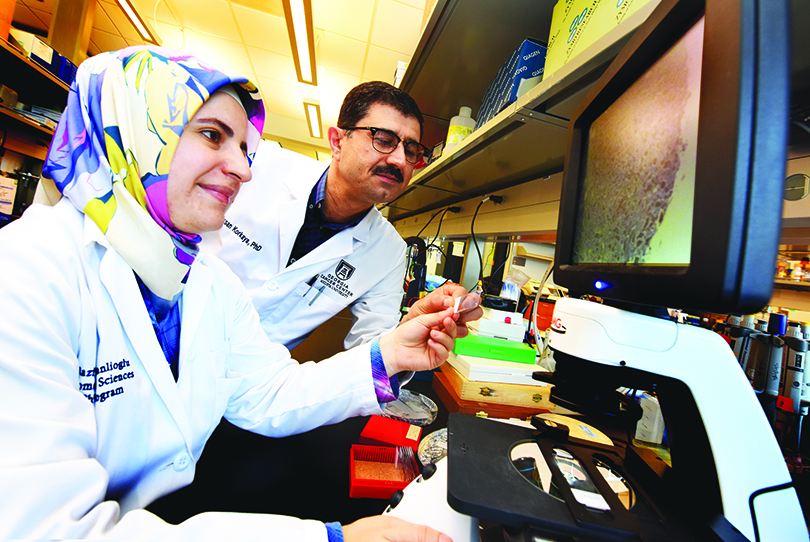

When a breast cancer tumor is removed with no signs of cancer left behind, it’s great news for patients, and now scientists have more evidence of why.

They’ve shown that once the breast tumor is successfully removed, the immune response turns its attention to destroying the tumor cells it has inevitably sent to nearby lymph nodes and organs like the lungs, says Dr. Hasan Korkaya, tumor biologist at the Georgia Cancer Center and Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

The fact that metastasis did not occur in their model even months later, indicates the immune system destroyed the disseminated tumor cells rather than pushing them into a dormant state, Korkaya and his colleagues report in the journal Nature Communications.

In contrast, when the primary tumor was not completely removed, the immune system appears to begin to support the tumor, which grows back faster and bigger than the original mass, and its disseminated tumor cells survive.

“We wanted to see if we could mimic what was happening in the clinic,” says Korkaya, the study’s corresponding author.

The scientists say what they found in their breast cancer model is likely true for other solid tumor types that can be surgically removed with no sign of cancer in adjacent tissue.

Tears May Hold Clues

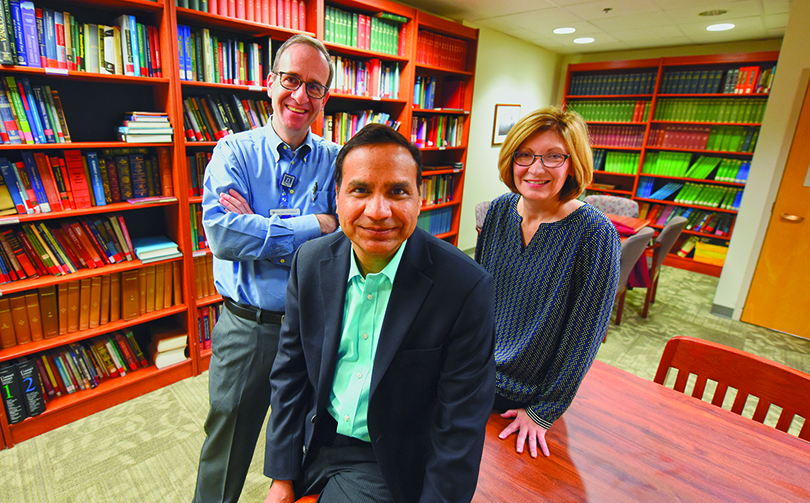

Contrary to what many of us think, high pressure inside the eye does not define glaucoma and investigators want to know if the proteins circulating in the fluid of our eyes might.

While some patients do have classic high pressure inside the eye, the reality is others with glaucoma don’t, says Dr. Ashok Sharma, proteomics and bioinformatics expert in the Center for Biotechnology and Genomic Medicine and Department of Population Health Sciences.

Since glaucoma, a leading cause of blindness worldwide, also has no clear, early symptoms, by the time patients realize they have a problem they can have significant optic nerve damage and vision loss, says Dr. Lane Ulrich, ’96, ophthalmologist in the Department of Ophthalmology and James and Jean Culver Vision Discovery Institute, and a study co-investigator.

Now MCG investigators are working to associate the protein profile present in the eye’s fluid with the obvious structural damage to the eye glaucoma causes. Their goals are to find a better way to diagnose the common eye problem, monitor its progress and maybe find new treatment targets. If they do, your tears may one day provide the fluid needed to perform such tests.

Sharma is principal investigator on a $1.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health that is enabling examination over the next four years of the fluid of 200 patients with glaucoma and 400 with cataracts serving as controls.

They are comparing the protein profile in the millionth of a liter of fluid, or aqueous humor, found in the eye – and removed as part of surgery – with clinical data, like images of a misshapen optic nerve, and other demographic and health data like age and race, to begin to write a proteomic signature for glaucoma.

They also are creating a database of the proteins and related clinical and scientific info they find that other scientists can access for their own studies. Eventually, the database may be expanded to include data from other labs, Sharma says.

Help for Optic Nerve Trauma

When a car crash or explosion results in an optic nerve injury, eliminating an enzyme known to promote inflammation appears to aid recovery, scientists report.

They have shown for the first time in a mouse model of tough-to-treat optic nerve trauma, that removing the enzyme arginase 2, which increases with injury, decreases neuron death in the retina as well as the degeneration of nerve fibers that connect neurons to each other and ultimately to the brain, they report in the journal Frontiers in Neuroscience.

“Right now when an optic nerve crush injury happens, there is not a lot we can do to help the eye recover,” says Dr. Ruth B. Caldwell, cell biologist in the Vascular Biology Center.

“We know we can’t prevent the initial damage, there is going to be some acute injury, but what deleting this enzyme seems to do is prevent subsequent amplification of the original injury. Collateral damage is less,” says Caldwell, the study’s corresponding author.

The findings elucidate both the role A2 plays in retinal damage following trauma and highlights A2’s potential as a logical treatment target, the scientists write.

Drug May Worsen Suicidal Thoughts

Nightmares and insomnia often accompany post-traumatic stress disorder and increase suicide risk.

Nightmares and insomnia often accompany post-traumatic stress disorder and increase suicide risk.

A small study looking at whether the drug prazosin, best known for treating high blood pressure but also used to treat PTSD-related sleep problems, can reduce suicidal thoughts has yielded surprising results.

They indicate it may actually worsen nightmares and insomnia and doesn’t reduce suicidal thinking, investigators report in the Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology.

“I think we have to view this as not the final word on this, but it raises questions,” says Dr. W. Vaughn McCall, chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Health Behavior.

McCall is currently seeking input from PTSD experts across the country but says a likely consensus could be that prazosin may help some, but may not be a good choice when suicide is an active concern.

Two larger studies in active and retired military personnel yielded mixed results as well, the first in active duty military showed it helped with nightmares and sleep quality and a follow-up study recently published on military veterans with chronic PTSD indicated it was no better than placebo.

McCall’s pilot study is the first in which all participants had suicidal thoughts or actions.

New Urine Tests for Bladder Cancer

Two new urine tests appear to accurately detect bladder cancer, determine its severity and detect its recurrence, investigators report.

The tests look at activity and levels of V1, a gene variant upregulated in bladder cancer that dissolves natural sugars in the mucosal lining of the fist-sized bladder, making it more vulnerable to cancer.

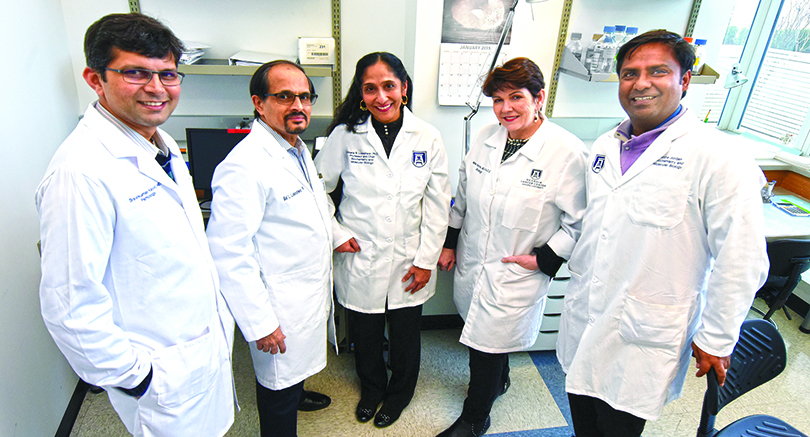

Investigators hope the tests will one day improve patient outcomes and reduce costs for a cancer that has both high mortality and treatment costs, says

Dr. Vinata Lokeshwar, chair of the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

Today there is no good, noninvasive method to determine if you have bladder cancer, says Lokeshwar. She’s principal investigator on a new $2.3 million grant from the National Cancer Institute and $608,000 grant from the Department of Defense that are helping determine if these tests can meet that need.

While there are several biomarker tests on the market, they are often expensive, don’t necessarily provide a lot of useful information, and have high rates of false positives and/or low sensitivity for cancer detection, says Dr. Zachary Klaassen, urologic oncologist and director of clinical urologic research in the Division of Urology and Georgia Cancer Center.

Consequently, Klaassen does not use these tests frequently, but would definitely like one that provides good information about the cancer’s grade and recurrence risk.

That’s why he is a co-investigator on these new studies that are pitting the new urine tests against the traditional methods he and others use for diagnosing and monitoring bladder cancer. They include frequent cystoscopies, where physicians place a small camera through the urethra – the tube through which urine flows – and into the bladder so they can directly see what is going on.