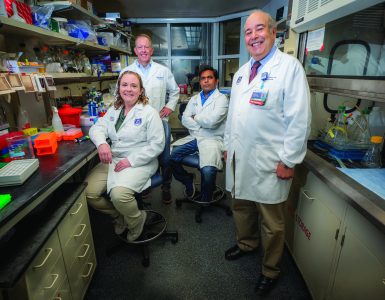

Dr. Jorge Cortes

Director

Georgia Cancer Center

His parents migrated from rural Mexico to the capital city for very different reasons. His father’s family was very poor and looking for work, his mother’s was middle class, and her father’s banking job brought them to Mexico City.

Jose and Cecelia Cortes met, married and had three children in this beautiful, bustling, historic place. Like his parents, their middle son Jorge loved his hometown, but somewhat inexplicably, before he ever saw it, he also loved the United States. “I tell my kids I was an American born in the wrong place. It sounded to me like a free country, a country with opportunities, a country with science, with sports, a place that people were able to, if they work and study hard, they were able to have a good life and to contribute.” He also tells his children how fortunate they are to be born here.

“My father is the proudest person of Mexico you will ever meet,” says the son. “It’s not that he wanted us to leave, but he wanted us to have opportunities … and options.” Jose Cortes did not want his children to struggle as he did, so he worked even harder to enable Cortes to attend an elementary school where he would learn English from his beginning. “I could see him struggling to pay the school,” but Jose Cortes always paid.

The son would not squander his parents’ investment. He went to medical school in his hometown at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in Mexico City. He completed his internal medicine residency, including a year as chief resident, and a hematology fellowship at Instituto Nacional de la Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, also in Mexico City.

He thrived in the practice of medicine and in research to find better medicine, and that would finally take him to his beloved United States because his country did not have the infrastructure or finances to enable all he wanted to pursue.

He would complete the last six months of his hematology fellowship at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston because of the strong research program there and his interest in blood clotting. Then he went next door to do a hematology/oncology fellowship at MD Anderson because his focus shifted to leukemia.

Finding focus

As part of his hematology fellowship, he would do rounds at MD Anderson. He would see suffering in patients with cancer, but he would also see progress in their treatment and wanted to be a part of it. He also saw Dr. Susan M. O’Brien, a leukemia expert and prolific investigator at MD Anderson, an exceptional, excited mentor who ensured that you learned, that she knew your professional interests and abilities, even knew when you were way overdue for a day off. What he saw in her, he wanted for himself, and he feels gratitude to and for her to this day.

In oncology training he would find more greats like Dr. Hagop M. Kantarjian, now chair of the Department of Leukemia at MD Anderson, an honored translational investigator who has helped make inroads in leukemia, like studies of one of the first targeted therapies called tyrosine kinase inhibitors. And Dr. Moshe Talpaz, a pioneer in frontline treatments for chronic myelogenous leukemia who today is a member of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia Guidelines Panel.

Cortes would join the MD Anderson faculty right after his fellowship; chronic myelogenous leukemia as well as acute myeloid leukemia would become his clinical and research focus, and he became principal investigator on his first clinical trial within a year.

He vividly remembers when he saw the first generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors used for the first time in patients in those early days, and how the drugs could put patients in remission when other treatments did not.

He liked the idea of these medical “missiles” directed at specific, problematic cells rather than more widespread cell destruction and side effects caused by “hammers” like chemotherapy. Cortes would lead the development of the second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor bosutinib and the third-generation ponatinib, which are widely used today. He also led the development of omacetaxine, a drug approved for patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in whom the missile tyrosine kinase inhibitors have stopped working. Most recently, he led the development of glasdegib, which targets cancer stem cells or “mother” cells. “If you cut down a tree but leave the roots it will grow back. If you leave the original cell, cancer also is going to grow back,” he says of his persistent foe.

In 2000, the man who was so inspired by his educators would start a leukemia fellowship at MD Anderson with one fellow for one year and no financial support, and grow it to 10 fellows per year with an option for a second year. Like his mentors, Cortes really enjoys working with more junior faculty and fellows, wants them to enjoy what they are doing as well and tries to lead by busy example. Part of the magic of working hard is enjoying what you do, he says, even when it’s fighting cancer. “It’s not a job, you are helping people.”

By 2002, Cortes was leading the AML and CML Section of MD Anderson’s Department of Leukemia and was deputy chair of the department. In 2016, he was named deputy chair of the Division of Cancer Medicine.

Leading by example

Dr. Jorge Cortes officially arrived at MCG and the Georgia Cancer Center in September and by October was seeing patients and onboarding clinical trials.

He responds with a methodical calm when asked about what else he hopes to help accomplish here.

He says today’s treatment cocktails, which take on cancer from different angles, just make common sense and he wants work at the Georgia Cancer Center to mix up even more powerful, and hopefully less toxic, cocktails.

Much like his analogy of pulling up tree roots, the tumor’s supportive microenvironment, which cancer builds at both its starting point and where it wants to spread, is an important target for attention as well.

Immunotherapy, which strengthens our immune system’s ability to attack cancer, is one of the biggest advances in cancer and definitely an area Cortes wants to expand. The reality is cancers are adept at hiding from or blocking the immune system.

“Now we are finding ways to make it work again,” he says, of the growing number of so-called checkpoint inhibitors, including monoclonal antibodies, which have broad applicability in tumors.

He wants to build a CAR-T center, where a patient’s own T cells, key drivers of the immune response, are engineered to better find and fight a patient’s cancer. A cancer immunology fellowship is one of the training programs he eventually wants to add to the immunology initiative.

Cortes notes the groundbreaking work already unfolding in this field at the Georgia Cancer Center and Children’s Hospital of Georgia. It started with a 1998 paper in the journal Science that showed the enzyme indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase is one way fetuses protect themselves from mothers’ immune response, and the subsequent finding that tumors also use IDO to protect themselves. In 2019, Dr. David Munn, pediatric oncologist, 1984 MCG graduate and a lead author on the original study, along with Dr. Theodore Johnson, also a pediatric oncologist and 2004 MCG graduate, began leading a Phase II trial sponsored by a $3 million grant from the National Cancer Institute that is the first study to examine the efficacy of an IDO inhibitor in children with recurrent brain tumors or newly diagnosed, particularly aggressive tumors called diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. The investigators have evidence that inhibiting IDO enables the child’s immune system to better fight the cancer and other drugs in their treatment cocktail, like chemotherapy, to work more effectively as well.

Stronger linkage between clinicians and basic scientists will enable the Georgia Cancer Center to ultimately discover and provide these kinds of clinical innovations, Cortes says. It’s a two-way synergy, he notes so that what is seen in the clinic can be investigated in the lab and vice versa.

One of the things that attracted him to Augusta and to the Georgia Cancer Center after 27 years at MD Anderson, is the diverse ethnicities and geographies it serves. He is proud that, under the leadership of Dr. Sharad Ghamande, gynecologic oncologist who chairs the MCG Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and is associate director for clinical trials at the cancer center, the center just received a $6 million renewal of an NCI grant that will help underserved individuals from across the largely rural state gain access to clinical trials. The center is one of 14 NCI Community Oncology Research Program Minority /Underserved Community Sites nationally.

But Cortes also wants to better understand the biology of disease in patients from different regions and backgrounds. “We know that different genetic backgrounds, different races, different environmental factors and nutrition, all impact what kind of tumors a patient gets and the characteristics of that tumor,” he says. “We need to understand those things to not only bring them clinical trials, but to bring them clinical trials most relevant to them.”

Under the leadership of Dr. Martha Tingen, associate director for cancer prevention, control and population health, the Georgia Cancer Center is making strong inroads in cancer education and prevention that Cortes also wants to expand.

Better understanding the biology of an often-devious disease that is not necessarily the same even in two people with the same background living in the same city, should also help steer more targeted prevention in addition to more personalized treatment, Cortes says.

After retiring from one of the top names in cancer, Cortes sees the opportunity to help build people and a place that is also a destination for patients, students, physicians and scientists alike.

“People are doing good work here. We will make it known.”

Snapshot: Dr. Jorge Cortes

Cortes would become a member of the Medical Advisory Board of the National CML Society in 2010 and of the Scientific Committee of the Society of Hematologic Oncology in 2013.

The new Georgia Cancer Center director, Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar in Cancer and prolific clinical investigator has authored or coauthored nearly 1,000 journal articles and helped develop mainstays in leukemia treatment like tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Cortes has served as a member of the Medical Advisory Board of the National CML Society since 2010, and a member of the Board of Directors of the International CML Foundation since 2009. In 2018, Cortes received the John Goldman Prize from the foundation for his lifetime contributions to treating patients with CML.

He is a scientific committee member of the Society of Hematologic Oncology, or SOHO, and a reviewer for the American Society of Hematology Scholar Award Program Study Section. He served as a member of the National Board of Directors for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society from 2007-13 and recently completed his tenure as associate editor for Blood, the official journal of the American Society of Hematology.

Cortes is a member of the editorial board for multiple journals including Clinical Cancer Research, American Journal of Hematology, Journal of Hematology and Oncology and BMC Cancer.

He is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of The Max Foundation based in Buenos Aires, which provides oncology products to underserved populations worldwide. Cortes also is president and founder of the Latin American Leukemia Net, based in Mexico City, an organization that focuses on patient education in Latin America.

Cortes received his medical degree from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in Mexico City in 1986. He completed his internal medicine residency, including a year as chief resident, and a hematology fellowship at Instituto Nacional de la Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, also in Mexico City. He jointly completed the second year of his fellowship at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston followed by a hematology/oncology fellowship at MD Anderson.

Despite his many professional accolades, it is his father’s compliment before family and friends that stands out most. Jose Cortes owned a tiny, old-fashioned market in bustling Mexico City and he was always there. “Every day of the week, every day of the year the store would open and he would be there,” says the son. The people who worked for Jose Cortes would rightly take days off, but not him.

Cortes was already in Houston and also working pretty much always, when his father said: “I finally found somebody that works harder than me.”” That made me feel very good because to me my father was the guy who never stopped,” says Cortes. His parents still live in Mexico City.