Two Spanish language professors — one a linguist, the other an expert in literature and translation — are enthusiastic if unlikely members of the James and Jean Culver Vision Discovery Institute (VDI), a group of Augusta University clinicians and eye researchers united to increase understanding of the eye and vision perception. The duo’s research into pupil dilation while learning a second language could transform the way foreign languages are taught and learning itself is understood. But without the intentional collaboration fostered by the Summerville Research Administration Office, this and other important research might never have developed to the point it has.

When Dr. Giada Biasetti and Dr. Chris Botero, both associate professors in the Department of English and Foreign Languages, began looking into the particulars of pupil dilation while learning a second language, a colleague on the Health Sciences Campus offered them the use of an eye scanner so they could measure how pupil dilation was affected by different elements of learning.

This was in 2013, and the Department of Physical Therapy was using the scanner along with a driving simulator to test the reaction time, cognitive workload and cognitive effort experienced by neurological patients while driving.

Basically, the more cognitive effort being exerted, the more the eye dilates, which is what attracted the Spanish professors.

“They were tracking their eyes and pupil dilation, and we thought it would be interesting to see what the cognitive workload is when someone is learning another language,” Biasetti says.

Utilizing the eye scanner, a postdoctoral student and some undergraduate research assistants, Biasetti and Botero measured pupil dilation as volunteer student subjects took a reading comprehension test in their own language to establish the cognitive workload they experienced in normal reading. They compared that to what it was when the same subjects started reading Spanish. Then, they measured the cognitive workload with Spanish over time.

“Tracking pupil dilation during certain exercises, we could see whether or not they were being challenged enough or challenged to the point where they were overwhelmed,” Biasetti says.

What they found surprised them. Contrary to conventional reasoning, which would suggest that ease comes with familiarity, they found that students were actually putting more cognitive effort into answering questions at the end of the semester than they were at the beginning, leaving the researchers to conclude that exposure to the language actually causes students to exert more effort when they know the rules, rather than when it’s all new and students often give up.

“If you overload their working memory, any information coming out of their cognitive system is going to kind of bounce off and not be absorbed,” Botero says. “And that’s one of the problems with learning a foreign language.”

They presented those early findings at three conferences, including one in Bologna, Italy, but when their colleague on the Health Sciences Campus took a job elsewhere and the postdoc moved away, the next step seemed in jeopardy until their department chair suggested they talk to Scott Thorp in the Summerville Research Administration Office.

Building on Momentum

In 2018, Dr. Michael Diamond, senior vice president for research, appointed Thorp associate vice president for interdisciplinary research, a new position. On paper it might have appeared to be an unusual choice, given the fact that Thorp was chair of the Department of Art and Design, a job he continues to hold. Though he lacked the typical pedigree most associate with research, his skill set was actually tailor-made for a position designed to bring campuses, departments and people together.

“If you look at everybody here who’s in research, the only one who really doesn’t know what they’re doing is me,” Thorp says with a chuckle.

But while Thorp may never have gone through an IRB approval himself, he knows how to listen; he knows how to translate institutional priorities for different audiences; and he knows how to break down structures into elements that make sense to just about everyone. When you’re looking at a 7-year-old university with a research mission and a 192-year history, that’s anything but easy.

The physical location of his research office is in Allgood Hall on the Summerville Campus, and along with the Center for Undergraduate Research and Scholarship (CURS), it’s also home to Walidah Walker, the interdisciplinary research manager, who makes sure the research proposals processed by the office have everything they need to succeed.

“Walidah is a machine,” Thorp says. “She’s incredibly knowledgeable, and faculty love working with her. She put in 73 proposals last year, and that’s with a range of people.”

Those 73 proposals resulted in $4.5 million in total impact. Including the research groups and outside research support, the office as a whole resulted in an impact of over $6 million and is on pace to double that production this year.

The Summerville Research Administration Office has been open for two years, and its influence has expanded in large part because of Thorp’s visibility and his willingness to make himself available.

“There’s so much opportunity if you’re willing to talk to people and fill out forms and sit on committees,” Thorp says. “I sit on a ton of committees.”

Sitting on all those committees and talking to all those people means he’s uniquely positioned to be a facilitator, a bridge builder who can help bring people together and make the whole much more than the sum of its already noteworthy parts.

While the Health Sciences Campus has always existed at the confluence of education and research, that dynamic hasn’t always been as integrated on the Summerville Campus, where research often manifests itself in different ways and is sometimes measured by different standards. However, Thorp says he’s seeing a kind of cultural shift going on at Summerville regarding research.

“We’ve activated the researchers and started a community on the Summerville Campus,” Thorp says “people are becoming more engaged and more understanding of the research process and how it helps them.”

According to Thorp, evidence of that engagement can be found in the fact that $672,000 of the $6 million in total impact was awarded to Summerville researchers.

Researchers from all campuses are starting to use his office as a starting point, however — a starting point that can become a launching pad for executing good research ideas.

“If someone says, ‘Hey, I’m interested in this topic,’ we’ll look at it and say, ‘Well, it seems like a pretty good topic — why don’t we just look around and see what other people are interested in related to that topic?’”

The Power of More

Bringing people together around a topic has proved successful in large part because of its simplicity.

“If you can form a group and talk and come up with some common ideas, then maybe you’ll come up with a project,” he says. “It’s worked really well.”

According to Thorp, the difference between saying “I’m a researcher doing this specific thing”, and, “This is what I’m working on. What do you do?” is subtle but profound.

“It’s one of those things where people come together and find a lot of common ground,” he says. “It quickly becomes, ‘I was looking at these grants but didn’t really know what to do, but now that I know you’re here, maybe we can work together on this.’”

Interdisciplinary Research Groups have formed around opioids, gun violence, neuroscience, Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES) and medical device redesign.

Each group is interdisciplinary, and the members are enthusiastic and engaged.

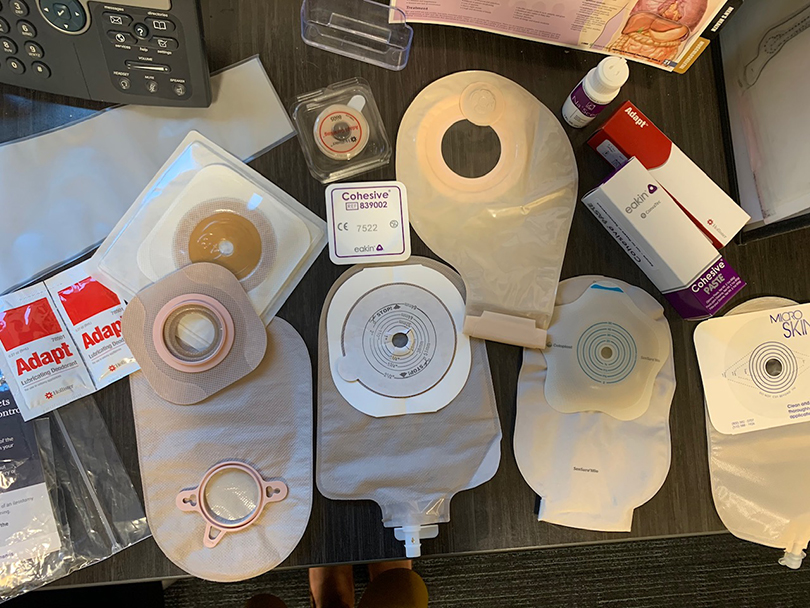

The group built around medical device redesign, a collaboration with the Center for Instructional Innovation, is starting with the colostomy bag, a waterproof pouch that collects waste excreted through an opening in the abdomen. It is used when bowel issues prevent waste from being eliminated by the natural process. Roughly 500,000 people in the United States currently have colostomy bags.

Lynsey Ekema, a board-certified medical illustrator in the Center for Instructional Innovation, mentored a 15-year-old girl who had worn a colostomy bag for eight years. In speaking with her parents, Ekema learned about some of the issues the girl was going through and how having the colostomy bag had changed her quality of life.

“I started thinking about it, and there’s so much brain power here,” Ekema says. “There’s medicine; there’s physics; there’s all this technology — why hasn’t somebody redesigned the colostomy bag?”

So she started reaching out to the physics department, the chemistry department, and the schools of medicine, allied health and business, bringing them together in the medical devices research group.

The redesign conceptualization is already being used in classes in the James M. Hall College of Business and the College of Nursing for collaborative interdisciplinary courses, and the project has added a Shark Tank-style competition built around solving the problems associated with the colostomy bag. Students will be given several options for earning course credit as teams work on business plans and pitch to a panel of judges.

The first Innovation Challenge Pitch Competition will be held on April 17, 2020.

Not only does the pitch competition work toward solving the problem of colostomy bag design, but it provides students with the kind of experiential learning opportunities that will help them as they pursue other research challenges or enter the highly competitive employment pool.

“The more brainpower we can put on things like this, the more we get things done, the more we can improve our patient care and give our students real-world experience,” Ekema says.

While the Interdisciplinary Research Groups are, by definition, interdisciplinary, there is cross-pollination even among the groups. Several researchers are contributing to more than one group, and according to Thorp, each group is experiencing success with their given topic.

The gun violence group consists of Augusta University faculty members from the Department of Social Sciences, the College of Allied Health Sciences, the Institute of Public and Preventive Health and the Richmond County Sheriff’s Office (RSCO). The group is currently working on a project funded by an intramural grant to build databases which will lead to predictive social network analysis for a more focused application of resources regarding the present G.I.V.I.N.G. B.A.C.K. focused deterrence program at the RCSO. It’s also collaborating with Augusta University’s trauma program on a new initiative to create a hospital-based violence prevention program.

The ACES group, now called Resilient Augusta, represents a broad community of members who are actively working to improve health care for area youth.

“We currently stand at 31 members and seven community partner organizations,” Thorp says.

Members of the group recently received a grant from the Pittulloch Foundation for $200,000 to implement a program called Resilient Teens. Principal investigator Dr. Kimberly Vess Loomer, associate dean for student and multicultural affairs, and co-principal investigator Dr. Melissa Bemiller, assistant professor of criminal justice and sociology, are spearheading the grant, and the group is teaming up with the IPPH to run a series of presentations and screenings of an ACES documentary.

The opioids group continues its work related to a $1 million federal grant from the Health Resources and Services Administration for its Rural East Georgia Response to Opioids Program (REGROuP), which was awarded to Dr. Aaron Johnson, director of the IPPH, and includes Dr. Vahe Heboyan and Catherine Clary, Director of Rural Health, who are also in AU’s opioids research group. REGROuP will provide a comprehensive approach to addressing substance and opioid use disorders in 22 HRSA-designated rural counties in East Central Georgia. The group is also a member of the Richmond County opioids task force run by the RCSO.

Finally, Dr. Almira Vazdarjanova and a research team of neuroscience investigators with backgrounds in biomedical and biobehavioral fields are designing a program that will prepare undergraduate students to enter doctoral programs in the neurosciences, particularly those from diverse or underrepresented backgrounds.

Joining Forces

When Biasetti and Botero went to Thorp, they weren’t sure what was going to happen to their research. Though their initial findings were promising and no one else was looking into pupil dilation in relation to learning a second language, they seemed to be at a dead end.

“Walidah and I took some notes,” Thorp says. “I followed up on some things and didn’t have much success, so I talked to Dr. Diamond and he said, ‘Why don’t you just call down to the Culver Eye Institute and see what they say?’”

Almost immediately, VDI leadership reached out, meeting them at their offices on the Summerville Campus. They were quickly asked to join.

As members of the Culver Institute, Biasetti and Botero are part of its monthly meetings while also having access to the institute’s pilot funding, anywhere between $10,000-25,000 depending on the year. All of which has the potential to move their research forward.

“If we know what the mind is naturally doing, maybe we can tailor classes accordingly,” Botero says. “If we introduce this type of verb construction and see through the dilation numbers that students are spending a lot of time focusing on that one structure in the sentence, that might be a good indication to maybe take that out so we don’t overload their working memory.”

And while that could directly impact the way he himself teaches a language, it’s not hard to imagine the implications it could have toward teaching in general.

“This could essentially change the way textbooks are written,” Botero says. “But right now, we only really know the tip of the iceberg.”