ECMO Sustains Life in Critical Situations

Lisa Churchill didn’t realize until later what this really was. On September 26, 2021, her friend arranged a visit to the crowded ICU as her chance to say goodbye to the love of her life.

Craig and Lisa had met at their small Christian school in the city of Clarksville in north Tennessee near the Kentucky border. They were and are opposites in ways. She is outgoing, today a paralegal for Wright McLeod Attorneys at Law, who won’t choose a confrontation but won’t walk away from one either, a force in her family who keeps lists and plans the near-perfect lives she and Craig would live with their two children Kayla and Tyler.

Craig is quieter and super methodical. Kayla laughs that her dad will drag them to seven stores searching for the right clothes at just the right price. But that persistent approach means they all have nice cars, nice homes, and yes good clothes. “Because of him we as a family have rarely made a bad decision,” says Kayla Hogan, 23 and married, marketing and public relations specialist for Meybohm Real Estate in Augusta. “He taught me to save and I taught him to live a little,” Lisa chimes in.

Kayla’s dad started his working life as a teen doing odd jobs at a small airport in Clarksville, would become an aircraft mechanic who would help keep big jets in the air, and today works in sales for StandardAero, an international provider of aerospace maintenance repair and overhaul. He would grow into an interesting mix of easy-going and doing, who might spend an entire Saturday cleaning up the yard and fixing around their home and cars whatever needed fixing. If something needs to be done, he does it, Lisa says. Craig likes to walk, sometimes run and play golf. He coached his youngest, Tyler, in competitive skeet shooting. Tyler, who clearly inherited his father’s ability to figure out what’s wrong and fix it, now works full-time for Augusta-based Sig Cox Heating and Air Conditioning.

On May 1, 2023, the Churchills piled onto a couch together for a laid-back family portrait and to share how they came way too close to losing the most methodical among them.

COVID kills

The world and the country were still scary, isolating, and sick places that September 2021, with the onslaught of Sars-CoV-2, the primary reason many hospital halls like the ones Lisa and Kayla walked that September day were eerily quiet while the ICUs were jam-packed and chaotic.

His wife and daughter could hardly recognize the man they came to see, who was extremely swollen with tubes coming and going everywhere. “I thought they sent us to the wrong room. It was very otherworldly,” Kayla says. Many of the patients were lying face down in their beds on ventilators in a technique called proning, which was thought to improve the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide. The staff told them to take Craig’s belongings home with them when they left.

The situation had started innocently enough about two weeks earlier for this active, healthy family. First Tyler, then Lisa, then Craig caught COVID, and the wife and son got pretty sick. Craig, then 51 and with no health problems or medications in his life, seemed comparatively fine for days and kept working from home except when he was helping take care of the others.

Then the morning of Sept. 20, 2021, Craig sat up on the bed and Lisa could tell he was having to focus on breathing. The pulse oximeter showed an oxygen saturation of about 86; 95 to 100 is considered normal. Lisa took Craig to prompt care, where he was quickly transported by ambulance to Piedmont Augusta, the former University Hospital, a large, community hospital in Augusta.

“I watched him get in the ambulance,” Lisa says because prevention measures in place at that time meant she could not get in with him. She knew that too many people were going to hospitals and never getting out. “It was terrifying and very, very lonely,” Lisa says.

Craig again seemed OK those first days. Her husband was still texting her, but it was not good news when the hospital called. He had experienced pneumothorax on both sides of his chest further burdening his COVID-infected lungs. Craig, who remembers nothing after arriving at the emergency room that Monday, sent her a text: “Dude, I just got a chest tube. Bam, I feel like I am on an episode of ER.”

His oxygen saturation had dipped into the 70s by then and he was moved to the ICU Sunday morning: He would go into cardiac arrest and need to be resuscitated. He was placed on a ventilator despite best efforts to keep him off this double-edged device that can damage the lungs it is trying to support.

But what Craig really needed was lifesaving support called ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, a temporary method that uses a device that takes over the work of the lungs and/or the heart and lungs and allow those essential organs to recover or physicians an opportunity to find a longer-term solution.

So-called destination therapies include an implantable left ventricular assist device, or LVAD, that supports the essential function of pumping oxygen-rich blood throughout the body, which is usually flawlessly and continuously sustained by a strong and health left ventricle of the heart. LVADs can be used temporarily if there is a high likelihood the patient’s heart can recover or inserted for permanent support to help improve the quality and length of life for patients who do not qualify for a heart and/or lung transplant to replace these irrevocably damaged organs.

The Churchills had never heard of ECMO before that day when Craig was put on a waiting list for an ECMO bed at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta.

An intense intervention called ECMO

Vijay Patel, MD, cardiovascular surgeon and medical director of the adult ECMO Program at the Medical College of Georgia and AU Health (which is scheduled to become WellStar MCG Health Sept. 1), first came across ECMO while doing a research fellowship in clinical transplant and research at the Texas Heart Institute in Houston from 1993-95. At Texas Heart, he learned among greats like O.H. ‘Bud’ Frazier, MD, who would become Patel’s mentor. Frazier’s mentors, which included the renowned Michael DeBakey, MD, and Denton Cooley, MD, were preeminent pioneers who implanted the first long-term LVAD and an artificial heart. Now in his 80s, Frazier remains a pioneer as co-director of the institute’s Center for Preclinical Surgical and Interventional Research. To this day, Patel keeps in touch with the man he says taught him at the bedside how to be a better physician, surgeon, and human. The self-effacing Patel seems to have learned those lessons well.

Patel came to the Medical College of Georgia in 2004 with the goal of bringing these types of complex care capabilities with him. His training took him from medical school and general surgery residency at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center in Houston and a research fellowship dedicated to mechanical cardiac support devices, extracorporeal membrane oxygenator devices and heart transplantation at The Texas Heart Institute to New York to study cardiovascular surgery at The Albert Einstein College of Medicine to North Carolina and Duke University Medical Center for fellowships in cardiopulmonary transplant and mechanical circulatory support devices and robotic and minimally invasive heart surgery. He was recruited to MCG by like-minded Kevin Landolfo, MD, whom he studied with at Duke and who had joined the MCG faculty that year to lead the cardiothoracic surgery program. They would start a heart transplant program and work to establish an LVAD program, but Landolfo would move to the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville in 2009. Patel was disappointed with Landolfo’s loss and would find himself MCG’s lone cardiovascular surgeon for a time. But the calm, committed Patel refused to bail just because things were tough.

Patel came to the Medical College of Georgia in 2004 with the goal of bringing these types of complex care capabilities with him. His training took him from medical school and general surgery residency at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center in Houston and a research fellowship dedicated to mechanical cardiac support devices, extracorporeal membrane oxygenator devices and heart transplantation at The Texas Heart Institute to New York to study cardiovascular surgery at The Albert Einstein College of Medicine to North Carolina and Duke University Medical Center for fellowships in cardiopulmonary transplant and mechanical circulatory support devices and robotic and minimally invasive heart surgery. He was recruited to MCG by like-minded Kevin Landolfo, MD, whom he studied with at Duke and who had joined the MCG faculty that year to lead the cardiothoracic surgery program. They would start a heart transplant program and work to establish an LVAD program, but Landolfo would move to the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville in 2009. Patel was disappointed with Landolfo’s loss and would find himself MCG’s lone cardiovascular surgeon for a time. But the calm, committed Patel refused to bail just because things were tough.

Long story shortened, the heart transplant program, which he plans to restart, had to go on hold and Patel would get the LVAD program up and running to provide support to patients at imminent risk of dying because of heart failure, which can lead to cardiogenic shock, a potentially deadly state where the heart simply cannot meet the body’s need for blood and oxygen.

Five years ago, well before anyone had even thought about the pandemic, Patel also started in earnest developing a formalized adult ECMO program because he continued to see patients that could not be helped otherwise. It became a hugely collaborative program that includes ECMO specialists, respiratory therapists who pull 12-hour shifts directly at the bedside of an ECMO patient; perfusion specialists, critical care nurses; nutrition specialists; physical therapists; cardiologists specializing in intervention and advanced heart failure; cardiovascular surgeons, pulmonologists, and critical care intensivists. The 18-bed cardiovascular ICU that opened in late 2021 became the place where these caregivers gather to provide patients on ECMO with the critical care management they need.

ECMO is a big-time intervention that is only used as a lifesaver when it’s relatively clear that meaningful quality of life can also be regained.

There was no COVID in the earliest days of adult ECMO, but heart or lung failure from other problems like a massive heart attack or other aggressive viral infections could quickly render these vital organs dysfunctional.

“We all get the flu and sometimes other types of viruses, in some individuals, severely attack the lung and/or the heart muscle, and then their inflammatory and immune systems can further exacerbate the injury to their lungs and their heart,” Patel says.

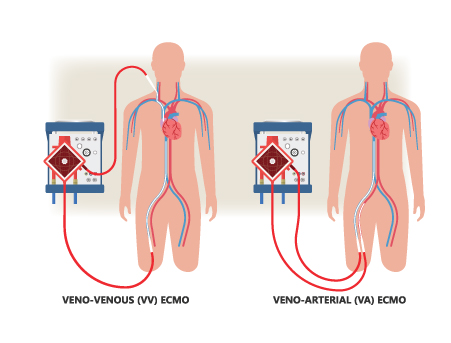

Venovenous, or VV ECMO, temporarily takes over the work of the damaged lungs so they can rest and maximize the potential for recovery; Venoarterial, or VA ECMO, is used when the heart and sometimes the lungs as well are failing. “It bypasses the work of the native cardiopulmonary system,” Patel says. Not surprisingly, the complexity of the underlying organ failure requiring VA ECMO carries a higher complication rate compared to VV ECMO.

While it literally feels like the heart and lungs would always live or fail together, that is not always the case. But there can be some unfortunate circumstances, like if the heart is failing acutely, fluid can back up in the lungs and cause them to also fail. The adult ECMO team may opt for VA ECMO support for these patients, Patel says, to allow the lungs to recover first, and the heart won’t have to work so hard, maximizing its potential to recover.

ECMO use in both adult and pediatric populations began in the 1970s, and the first decades of experience with adult ECMO worldwide were not exceptional. Many adult patients died, most likely because of the early technology and poor timing and patient selection, Patel says, in addition to the numerous risk-contributing medical illnesses and comorbidities common in adult patients compared to the more resilient pediatric populations.

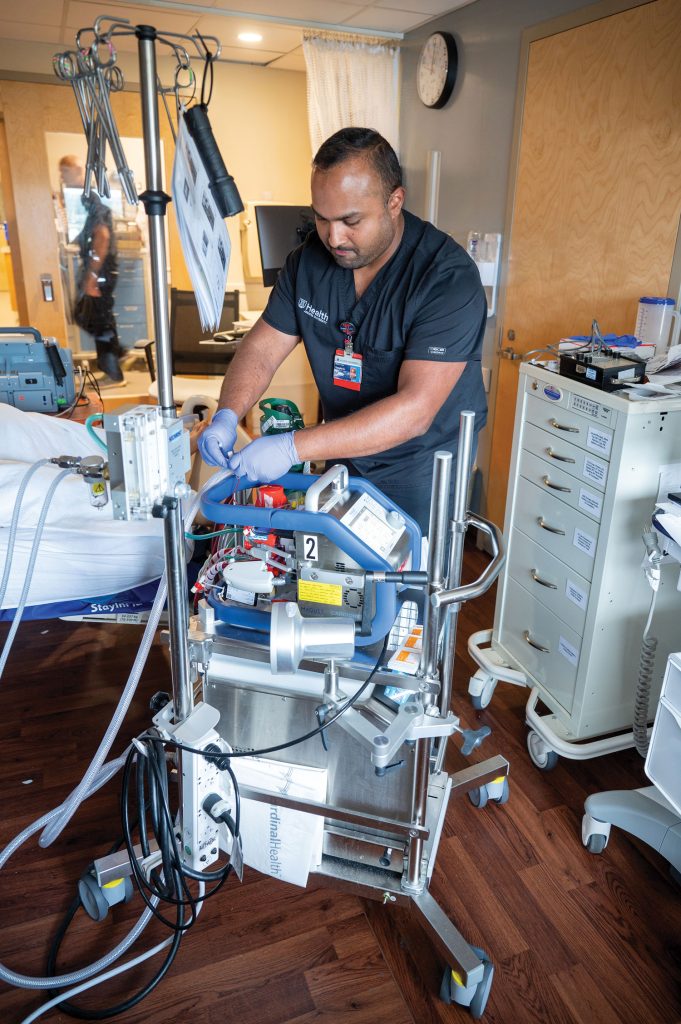

Today, oxygenators, essentially external artificial lungs, are better; the pumps that keep blood circulating are better; and the multidisciplinary critical care teams that today includes ECMO specialists like AU Health’s Sangley George constantly at the bedside is significantly better as well.

So is the patient selection, which is key and likely one of the hardest pieces because these patients face essentially certain death without ECMO. But this level of intervention carries big risks as well, including the extremes of bleeding and clotting, new infections, seizures, muscle wasting and stroke, among many other potential complications that can all linfluence outcomes and meaningful survival. Patients can have cognitive impairment and mental struggles afterward, like post-traumatic stress disorder. A different harsh reality is that ECMO is resource intensive and expensive.

For these reasons and more, there must be viable long-term options for patients, like good evidence the heart and/or lungs can recover given time and the right medication or that an LVAD or transplant could work for them. “They are going to die if you don’t put them on ECMO, but they have to be able to survive if you do,” says Patel. Older age and comorbid conditions that already likely shorten lifespan must be considered. So, Patel talks with the adult ECMO team members about those decisions, but ultimately the buck stops with him.

ECMO versus COVID

COVID made those tough decisions more challenging across the globe and at the new adult ECMO program at MCG and AU Health because it was overwhelming the entire health care system and wearing out the brave frontline healthcare workers.

The ACE2 receptors prevalent in the lungs, as well as the heart and kidneys, are like a lock and key with this spikey coronavirus. Adult respiratory distress syndrome, or ARDS, which results primarily from bacterial and viral infections, became a death sentence for many patients as millions of tiny air sacs in the lungs fill with fluid, a surfactant that helps keep air sacs open breaks down and oxygen levels drop. Pressure mounted as ECMO teams across the country realized that if you were going to use ECMO, it was best to intervene early. While he doesn’t seem like that person, Patel acknowledges that he was on edge for the duration of COVID as local and national discussions ensued about how best to guide teams about when and how to use ECMO.

Patel and his team found their capabilities often maxed out during the pandemic. So, they would call nearby adult programs like the one at Emory Hospital in Atlanta, and Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston as well as programs in Tennessee, Florida, and Alabama. He remembers receiving calls from other states asking him to accept eligible ECMO patients for care at AU Health. His most memorable call was for a young woman from Florida who was pregnant, who called him directly. The ECMO program was at capacity and people were still walking in sick. He still wonders what happened to her and her baby.

As the Churchills waited precious minutes to hear from Emory about an ECMO bed becoming available, Lisa uncharacteristically went to social media that Monday morning, Sept. 27, sharing that her family needed the prayers of their people.

Two houses up, Amanda Wright, who at the time was the trauma nurse manager at AU Health and had helped spearhead COVID vaccinations for her fellow healthcare workers, texted Lisa the news that MCG’s adult teaching hospital had an adult ECMO program. Its Children’s Hospital of Georgia had one of the first half-dozen neonatal and pediatric ECMO programs. Tyler had grown up with Amanda’s children, but this was no doubt the best news she had ever shared with them. At about the same time, a good friend of Craig’s saw a local news piece about the adult ECMO program. “God’s handprint is just all over it,” Lisa says. A doctor at Piedmont called to say Craig would be transferred to AU Health later that day, but there were concerns about his surviving even the one-block trip.

Patel met Craig in the operating room and by 8 p.m. that night, Craig was on ECMO.

“He became so hypoxic because his lungs could just not support him no matter how much oxygen you gave him,” says Patel, and the ventilator, while invaluable most times, could not fully accommodate for that. “He was never going to survive by standard treatment.”

Craig’s heart was fine, so they used VV ECMO which would just take over the work of his lungs. Patel put a large cannula into the right side of his heart to drain the oxygen-poor blood, which ran through the oxygenator and, now rich with oxygen and low on carbon dioxide was put right back into that cannula so it can continue the rapid, normal path starting from the right side of the heart, through the pulmonary artery and to the lungs, then finally to the left side of the heart and out to the body. In Craig’s case and often, they started with ECMO support wide open.

Antivirals and old-school diuretics and steroids help deal with the underlying issues — the causative virus itself and resulting excess fluid and inflammation. Rest and healing for the lungs should result. As the lungs start to shake off their injured state, their contribution to helping Craig’s body get adequate oxygen increases and the ECMO machine can start to be turned down. The ECMO team starts thinking about how to get a patient off ECMO as soon as they are put on it.

But again, this is big-time critical care, and the course is not always so direct. Craig would end up having the team’s longest course on ECMO, a total of 44 days while the “normal” for COVID is closer to 2.5 to 3 weeks and maxing out on ECMO support. One probable reason was Craig would develop severe gastrointestinal bleeding, likely resulting from the severe stress he was under and the powerful steroids he needed. Arthur Freedman, MD, chief of Vascular and Interventional Radiology at MCG and AU Health, identified and embolized the problematic blood vessels. Craig’s recovery improved after that. A confounding issue that remains an issue today is that at some point over the course of his illness, Craig also had a stroke. Stroke is a clear risk of ECMO, but Patel suspects Craig’s likely occurred when he developed cardiac arrest due to a severe lack of oxygen arrested and needed CPR before his ECMO course.

Patel notes that while ECMO has been around for decades, COVID has not, consequently it provided a tremendous learning curve for those around the world who would step up to take COVID on. The lessons the medical community learned over many decades managing these very sick patients and the advances in technology that made ECMO therapy possible became even more valuable in the face of the pandemic.

“He became so hypoxic because his lungs could just not support him no matter how much oxygen you gave him,” says Patel, and the ventilator, while invaluable most times, could not fully accommodate for that. “He was never going to survive by standard treatment.” –Vijah Patel, MD

Better sooner than later

The experience was how they would learn that sooner is better if you are headed toward ECMO and that if you put patients on ECMO beyond seven days of being on a ventilator, they are less likely to recover. Not surprisingly, they found that being young, improved survival chances, and being older decreased them. That the multiplier effect of existing medical conditions, particularly those that increase inflammation was a negative, and inflammation is a factor in most major illnesses as well as obesity.

Seemingly amazingly, and ultimately, Craig’s lungs began to heal, and indicators of inflammation went down as his oxygen levels crept up. Lisa and Kayla watched as the number of medicine drips beside his bed decreased and as all those tubes started to come out.

Craig thought it was the next day when he woke up at Select Specialty Hospital in Augusta, an inpatient rehabilitation hospital where he spent about three weeks before going to the renowned neurorehabilitation center, Shepherd Center in Atlanta for another month.

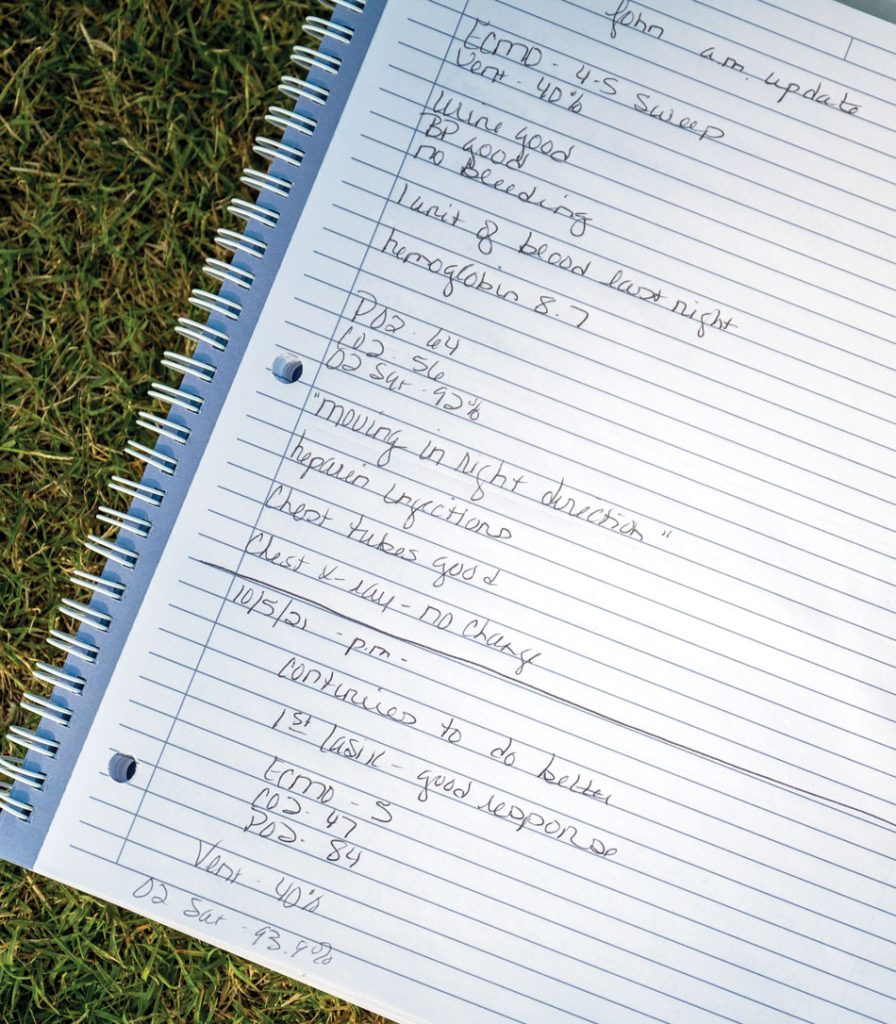

Lisa would keep a detailed notebook of the entire dramatic course and share the often-rocky path on social media and continue to ask their people to pray. Kayla was her goal-oriented right arm while Craig was in the hospital and Tyler was her support when she got home.

Today a visitor would never know that Craig Churchill was any worse for the significant wear. He smiles a lot, plays golf, is walking and running again, goes to the gym several times a week, and was back at work full-time on March 1. The man who could barely get up to go to the bathroom alone when he got home, has gained about 30 pounds of muscle in the last year.

But there are reminders of the dizziness he still feels, the fact that he still must focus on his breathing, particularly when he is talking or eating, and to make sure the words he is saying are what he wants to say. He says he can’t yet hold a cup of coffee in his left hand, which was news to Kayla that May 2023 Day.

It’s been tough and still is tough on everyone in the tight-knit family. Tyler didn’t see his father until he was at Select, admitting that he did not want to see his “big, strong father figure” lying on his back. “It was hard for him. It was hard for me to see. It was hard for his mom. It was hard for Kayla,” Tyler says.

But Kayla says there also are additions to her father, as he talks more, he is funnier and more emotional, quicker both to kindness and to anger.

Lisa says she thinks the whole family has PTSD and does not disagree that the whole country does.

Craig says no one has not been touched in some way by COVID and that his battle with it was the hardest thing he has ever done. Was it worth it? “Yeah.”

The adult ECMO Team

Akbar Herekar, MD, says it’s natural for anesthesiologists to also function as critical care specialists at the bedside of patients like Craig.

“What happens in the ICU over three or four days, happens over a couple of hours in the OR. So naturally anesthesiologists are very good at managing the ventilators, putting patients on ventilators, managing the breathing tubes, and then managing their blood pressure and hemodynamics because we must know the details and the nitty-gritty of the way the medications work, how they work, how we push them, how we get access.”

It’s like doing intensive care at super speed, says the young physician, who completed his anesthesiology training at MCG and AU Health and an anesthesiology critical care fellowship at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore before joining the MCG faculty in 2020. Among the sickest of the sick, critical care specialists essentially become frontline physicians looking out for the whole patient, for everything from nutrition to blood pressure to urine output to alertness to signs of a new infection from all the devices the patient has in place. At Hopkins, Herekar found himself in the thick of the pandemic at a center leading the nation in treatment and in providing the nation with near real-time updates on COVID cases.

Herekar’s immersion and expertise quickly became a huge asset in bringing cohesion to the new team caring for ECMO patients at MCG and AU Health, and in helping orient the critical care fellows in the MCG Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Patel says. Herekar returns praise to Patel for championing an effort that was sorely needed and eerily timely.

He loves what he does at the bedside of truly sick individuals, like those on ECMO, and the privilege of helping save a life. But getting them back to life is always on his mind and the mind of every team member.

“COVID especially has helped us realize that it’s not just about keeping patients alive, but about helping bring them to where they can live a meaningful life,” he says.

With that ultimate goal in mind, Herekar is part of a national movement to get critically ill patients, including those on ECMO, out of bed and off the ventilator as soon as possible. You can find videos online of this somewhat astounding feat.

When the team does rounds, he likes to have everyone stand inside the door to ensure that the patient can hear what is being said if possible and any family members present know as well. “They need to be part of the team. They need to know what decisions we are making and it’s important that we ask them where you want to go from here. Back to his good life, is how Craig Churchill answered that question when he could.

It’s really because these patients are so sick and because they are likely to be sick for so long that this sort of revolution is happening, Herekar says. The culture has been to keep sick patients like these deeply medicated and on traditional ventilation, but both can be problematic. Patients with ARDS, for example, have a portion of their lungs already significantly damaged, likely by infection, and the positive pressure of even modern ventilators which push air into the lungs can damage the healthy portion of the lung and nothing helpful for the already unhealthy portion.

Most people don’t recognize the energy it takes to just breathe, but when patients get so sick like Craig, they do feel it and the ventilator can help support the essential function until they do have the energy, adds ECMO Specialist George. “A ventilator is great in situations outside of severe ARDS. When we pull ECMO off the shelf, is when a patient is in severe ARDS, and what we are doing on the ventilator is not making a difference. Their lungs are so stiff, so non-compliant. A ventilator is great in situations outside of severe ARDS because we have lots of people on ventilators right now that will come off and be no worse for the wear,” he says.

And afterward, these patients can experience “post-intensive care syndrome,” which the Society of Critical Care Medicine defines as health problems that linger after the critical illness, from problems with muscle weakness to troubles with thinking and judgment.

Under constant heavy sedation and without any movement, caregivers can’t see signs of a stroke or whether the patient can even move their arms.

“We would keep them alive, but they would have some sort of memory deficit, they wouldn’t recognize who they are, and it would take them a long time to recover afterward,” Herekar says.

Eugene Wesley Ely, MD, pulmonary and critical care medicine specialist at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, wrote Every Deep Drawn Breath about this unnatural state in which patients can spend weeks or even months and which can leave them with a form of PTSD, sometimes seeming normal, but unable to do normal things.

“They wake up, now they have their hands and legs tied, they have a breathing tube and are on a breathing machine, they have things in their neck, so they wake up and every normal human being is going to be agitated at that point,” Herekar says. “We give more medicine because they are agitated, and they wake up again and the cycle happens over and over.” At the busy ECMO unit at Johns Hopkins, Herekar learned: “When it’s time to decannulate just do it.”

A delicate dance

Still, it’s a delicate dance. Patients with ARDS, like Craig, clearly need help getting oxygen into their bodies, so they are placed on a ventilator and medications to optimize their comfort and adjust to being on a ventilator, in an effort to avoid being placed on an ECMO.

But the realities also are that the sedation drugs they receive linger in the body and artificial intelligence has helped to be on a ventilator feel more like breathing and likely less scary. Being sedentary also is not good for the physical or mental health of anyone, and these patients can have challenges in both places.

“Are they dancing in the halls now? No, but at times they will sit up in bed and turn the television on.” That is when Herekar pulls up a chair beside them. “We are not sitting there talking about them, we are talking to them. Treating people like people.”

It’s not good for blood to sit around either, Musa Sharkawi, MD, says. Team members agree that the respite for the lungs and/or heart that ECMO provides is a technique like what happens during the 350,000 coronary bypass surgeries, or CABGs, performed each year in the U.S.

But for bypass surgery, the vital organs rest for a few hours. With ECMO it can be for days, weeks, or longer, like with Craig.

If their heart rests that long, blood essentially starts to curdle. “It has 100 percent mortality,” says Sharkawi, an interventional cardiologist. That’s why, particularly patients on VA ECMO, may also need an Impella heart pump, essentially a miniature LVAD that can be inserted via a catheter into the left ventricle, the major pumping chamber of the heart, to keep blood moving along through the ascending aorta and out to the body.

“Having an ECMO program is much more nuanced and complex than just putting catheters in, putting a pump on and that is it,” Sharkawi says. That’s why there are many educated eyes always watching, including Sharkawi and heart failure specialist Evan Hiner, MD, Herekar, ECMO Specialist George, and Patel.

The heart is now the main matter

Now that the pandemic has passed and with heart disease Georgia’s and the nation’s steadfast number one killer, most of the adult ECMO cases the team is seeing are heart-related so cardiologists like Sharkawi and Hiner often get the first call.

Like the January day 42-year-old Steven Herrington’s heart stopped twice in the Emergency Department, and Patel and Sharkawi placed Herrington on VA ECMO while they were still doing CPR with chest compressions. Despite Steven being on the VA ECMO, his heart wasn’t moving and the blood was pooling. The team, never having encountered this before, had to think fast. They strapped on a chest compression device, called a LUCAS device, at that critical moment. Then Sharkawi took him immediately to the cardiac catheterization lab to put in the Impella. “Man, it really did take a village,” says Sharkawi, who is proud of what the village did that day and more.

Sharkawi, who did his cardiovascular medicine fellowship at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine and interventional cardiology and structural heart and peripheral vascular intervention fellowships at Brigham and Women’s Hospital of Harvard Medical School, says the adult ECMO program Patel pursued was “absolutely” a drawing card for him when he joined the MCG faculty in 2021. Hartford Hospital in Connecticut and Brigham and Women’s Hospital both have ECMO programs.

“If, for example, we were at another institution without these capabilities, particularly having a young patient like (Steven) come into the emergency room, it would feel a little bit helpless not being able to help him,” Sharkawi says. “Now there is almost nothing in acute cardiac care that we are unable to do.”

That’s a good thing, since there is increasingly more that needs doing. Colleague Hiner, the heart failure specialist on the adult ECMO team, says. “Heart failure is a growing epidemic, we are seeing greater prevalence in this disease as patient’s continue to live longer due to improvement in overall therapies that are now available.”

Oddly the heart can be in failure both because it can’t pump sufficiently because it’s weak and because this important muscle can’t relax sufficiently to pump sufficiently. Patients go into cardiogenic shock because the heart is no longer meeting the demands of the body and a major heart attack that puts 40% of the heart muscle at risk is the most common cause. “So, it’s a pretty serious heart attack to get to cardiogenic shock and the need for ECMO for these patients is at the extremis end, but when patients need it, they need it quickly,” Hiner says.

The goal is to identify the cause of a patient’s heart failure, establish a treatment plan and provide prognosis during their hospitalization. The causes are a diverse list that also includes hypertension, valve disease, alcohol consumption, viral infections, chemotherapy, radiation and irregular heartbeats.

His goal is to get these patients in “remission” ideally with guideline directed therapies aimed to remodel the heart and prevent further negative consequences. He notes his cardiac colleagues have changed their language and terms of ‘remission’ instead of ‘recovered’ to emphasize patient trajectory and importance of maintenance medications.

Getting back to their lives

In his 12-hour shifts at the bedside of patients who do need ECMO, Sangley George’s eyes continuously monitor the intricate, temporary network holding about a third of the patient’s blood volume at any one moment. His eyes shift from the pump itself which functions like a lung or heart/lung; to the big plastic tubes cannulas in the neck or groin area that are sending blood to the pump, where it picks up oxygen and loses carbon dioxide before being pumped back to the heart and lungs; to the tubing connecting the patient to the pumps; and at the pressure on the blood flowing through the generator, a good indicator of how it’s working. “If we see a spike in post-pressure, for example, that tells us there might be an increase in clotting that is happening,” he says. Without adequate speed, the blood will quickly form those dangerous blood clots.

It was both the intensity and potential of ECMO that made George raise his hand to join the adult ECMO team. He’d only been a respiratory therapist for a few years, but was ready for more, ready to be one on one with patients like Craig who needed super-critical care. “I think of it as therapy that is buying time for the patient,” he says. “Can we buy them a little bit more time to where we can allow the lungs to heal, we can allow the heart to kind of heal up.”

The ECMO team bought Craig more than a little time. Thirty days were the longest George had seen a patient on ECMO before Craig. And after 30 days, it usually didn’t go well.

George would see Lisa most days of the extraordinarily long journey. Lisa says he and his ECMO specialist colleagues quickly became like her best friends. The Churchills, in turn, helped define hope for George in these also extraordinary times.

“You just kind of gravitated toward the hope that they had.”